Cherry blossom has arrived in Kyoto! The trees along the Kamogawa are out in glorious bloom, and people are flocking to the petals in Hirano Jinja, Kyoto’s special shrine for cherry blossom. Today was a fine day for the emerging blossom, and the crowds were out in force. Next weekend is sure to see a peak.

Hirano Jinja is one of thirteen Kyoto shrines in Cali and Dougill’s Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion (Univ of Hawaii, 2013). From that we learn the shrine was founded in 782 in Nara, before being relocated to the new capital of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 794. The present buildings date from 1625, and with their unpainted wood and cypress-bark tiles they present an evocative rustic appearance.

The shrine has long been considered prestigious. It may have been intended by Emperor Kanmu to guard the north-west of his new capital, and the Engishiki (967) mentions it as guardian of the imperial kitchen. It was one of only 16 shrines to receive regular offerings from the emperor, and the hereditary priests were drawn from the powerful Urabe clan who specialised in tortoise-shell divination. (The Urabe were one of the three ‘houses of Shinto’, who later divided to form the influential Yoshida lineage.)

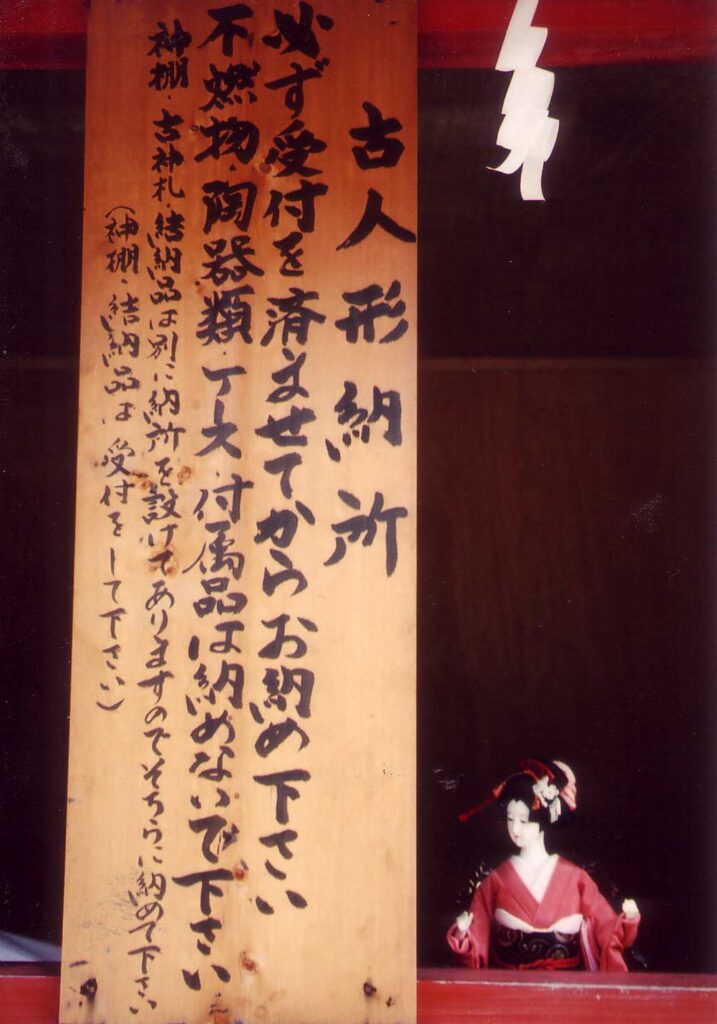

The four Hirano kami are unusual. According to the shrine, Imaki okami is a god of revitalisation; Kudo okami is a deity of the cooking pot; Furuaki okami is a deity of new beginnings; Hime no okami is a deity of fertility and discovery. There are suggestions of links with Paekche (in ancient Korea) and that the last kami is in fact the ancestral spirit of Emperor Kanmu’s mother, who was descended from a king of Paekche.

The people who throng the shrine these days are little concerned with history, however. Their concerns are with saké, picnic, conviviality and the brief glimpses of the moon appearing through clouds of pink blossom. Within the compound are some 500 cherry trees, and the shrine was noted even in Heian times as a place to go for blossom viewing. Now with lanterns dotting the grounds and a classical guitar strumming ‘Sakura’ in the Haiden, the shrine is a celebration of spring renewal and the touching brevity of life in this world.

Cherry blossom selfies are always popular

Even without cherry blossom the Honden (Sanctuary) has an attractive air with its gabled cypressbark roof, slender chigi crossbeams and goldplated details such as the imperial chrysanthemum

As evening falls, the stalls begin to do good business with people arriving after work for ‘hanami’ (blossom viewing parties)

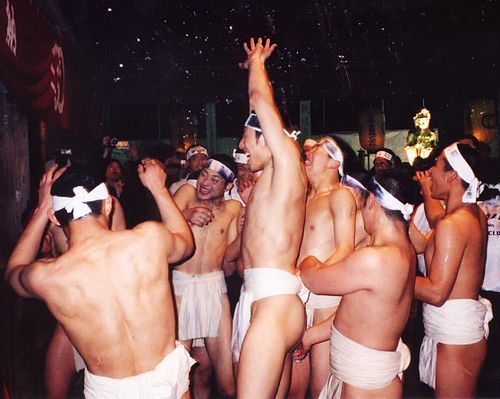

For some, partying takes precedence over cherry blossom

For others the combination of moon and cherry blossom is enrapturing..

Paper lanterns painted by primary schoolchildren adorn the grounds