The island of Shiraishi in the Inland Sea is studded with rocks of so many sorts and sizes that you can’t help being ‘struck’ by them. Small wonder it’s called White Rock Island, and that sacred rocks are numerous. Some are distinctive in themselves. Some have a brooding presence. Some are sanctified by tradition.

Shiraishi's Big Spirit Rock

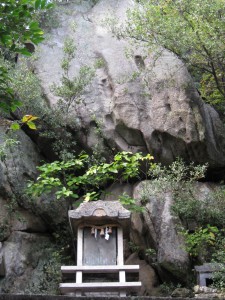

The Okunoin of the island's temple

There’s a power stone lifted by a superman called Ichirobei after he had prayed to Kobo Daishi, the legendary founder of Shingon. Daishi supposedly meditated on a large rock, beneath which is the Okunoin of the island temple, showing that Buddhists too feel the power of rock.

The island boasts a rock that looks like a warrior’s armour, and one that bears the ghostly visage of a slain samurai at a shrine dedicated to the Genji-Heike war victims of the twelfth century. There’s a rock which is celebrated as a phallic symbol, and there’s another in a womb-like opening that resembles a woman’s anatomy. The hills are alive – with yang and yin!

Long live rock!

The power stone of Ichirobei

What is it with Japan’s sacred rocks? Why are the kami so fond of rock? For years I couldn’t understand. None of the books on Shinto offer explanations, and the priests I talked to had little to say beyond the observation that kami manifest there. But why rocks? And why did kami travel in ‘rock-boats’ in the mythology? If you’re going to travel through space, rock doesn’t exactly spring to mind as the obvious material.

It was only after reading Mircea Eliade’s The Forge and the Crucible that I found an answer. ‘The stone parentage of the first men is a theme which occurs in a large number of myths,’ he writes. ‘Stone was even believed to be the source of life and fertility.’ Say what?

It seems for ancient humans rock represented absolute reality. Something durable, ever-lasting and undeniable. It contrasted with the ephemeral world of humans. It was a rock of ages. Moreover, it gave birth to minerals and jewels. It was not only alive, but had mythical and magical properties.

I’m a huge fan of Alan Watts, who continues to live on in a virtual afterlife thanks to ipod broadcasts. ‘Rocks are not dead,’ he declares in one of his talks, proceeding to illustrate the point by suggesting that if aliens were to visit the earth they would not think of it as a dead rock floating in space but as one that had spawned life. In the same way that trees bear fruit, earth has produced living creatures.

Kami as rock stars

The spirit of rock permeates Shinto. Kami manifest in rock. They travel in rock boats. They inhabit spirit-bodies made of rock. They gather round the rock cave of Amaterasu, and they have a celestial rock seat. In a sense they are truly rock stars.

In Myth in History Peter Metevelis claims that ancient Japanese thought that the sky as a whole was made of rock. It’s perfectly logical if you think of meteorites as bits of the sky that have fallen off. Not far from where I’m typing this is Mt Kurama, where one of the deities worshipped at the temple is Mao-son who supposedly dropped to earth from Venus thousands of years ago. How did the deity travel? Not in a spaceship, but in the prehistoric equivalent: a rock-boat.

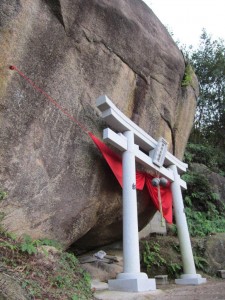

Bikuni iwa on Shiraishi Island, focal point for the hill as a whole

In Shinto mythology, when Izanagi escapes from the death-tomb of Izanami, he seals up the burial place with a rock. It’s similar to the way that ancient rock tombs were sealed with a stone door. Over time the rock of the door came to symbolise the dead spirit behind it, as if it had absorbed the soul of the deceased. In this way rock, death and spirit were closely associated. To the neolithic mind the idea that rock had spirit was as much common sense as it is strange to us.

Mountains are the closest humans can come to heaven, and they make a natural landing place for the descent of kami. Rocks one-third up a mountain served for early worshippers as a focal point for the mountain as a whole. Rocks with a special shape, or of a special nature were seen as sacred, possessed by a divine life-force. In this way rock came to act as the interface between the natural and supernatural worlds.

Sacred rock; sacred mountain; sacred earth.

Honouring the spirit

Gateway to another realm

The rock face of an unseen world. An accompanying sign says, "On this rock, Bonji (Sanskirt characters) by Fudo are written. It's said that if you trace these letters with your eyes closed, you can improve in calligraphy or progress in your study."

I recommend Mythical Stone by Peter Metevelis for a study of stone in japanese mythology

Hi, thanks for that, Jake… I agree with you. ‘Mythical Stone’ is Volume I of his Mythological Essays, and ‘Myth in History’ Volume 2. Since much of the material is not available elsewhere that I’m aware of, I’m surprised they are not more widely known or referred to in the literature…

I`m in Japan at present. I`ve been to Shiraishi Shima and also visited many Jinja. Soon I`ll be returning to Australia. I`m interested in how Shinto can be practised in places outside of Japan. Australia has many huge, awe-inspiring rocks (Uluru etc). I`d like to know your thoughts on this Dougill. Can I practise a form of Shinto in Australia where there are no Jinja but there are many huge trees, rocks etc? Is Green Shinto part of the answer?

Hi there, Iandalf…

It’s an interesting question, and one to which I’m sure people have different responses. I’d say it’s very much a matter of individual conscience. Shinto priests would likely advise you to keep as close to orthodoxy as possible. One person who’s managed that is Douglas Bostok: http://www.greenshinto.com/2011/10/08/a-shintoist-in-europe-douglas-bostok/

I’m not a priest however and am more inclined to unorthodox approaches. I’m also more in tune with early Shinto than the post-Meiji model. There is some inspiring stuff on the internet about how people have adapted Shinto to their own personal belief systems, such as developing meditation techniques based on entering through a torii and communing with a particular kami. There are also those who’ve integrated Shinto into neo-paganism. In that respect I wonder if there is room for adapting Shinto to the aboriginal beliefs of Australia?

There are people who are outraged by such suggestions, believing them to belittle or negate the force of tradition. But the history of religion, and of Shinto in particular, shows that it has happened all the time. Think of all the Chinese beliefs that Shinto appropriated. The fact is that Shinto has changed dramatically over the centuries and there’s no reason why it should not continue to do so. We live in a global age which is characterised by a sharing of traditions. Instead of resisting in reactionary manner, why not embrace the opportunities it offers? Why not be an internationalist, instead of a narrow-minded nationalist?

Pioneering an Australian form of Shinto could be an exciting prospect….

Thanks, first, for the info & photos & links posted.

Before Watts got into stones, we find Muir speaking of them as old friends and though moderns find the blood he feels racing through their veins etc ridiculously anthropomorhic (actually it is just zoomorphic), if you know Muir you do not feel that way.

To me, the main lesson is aesthetic. What does Shiraishi’s Big Spirit Rock have to say about modern art? About classic art? About the rlationship of environmentalism and landscape (we speak of the diversity of biological species but what about rocks?).

Thanks, Robin, for the thoughts… I guess for Muir rocks were a part of the Divine purpose: “Every particle of rock or water or air has God by its side leading it the way it should go; The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.” It’s a bit different from the Shinto concept, but the idea of God beside the rock is strikingly similar.

As for the aesthetic consideration, that’s a stimulating way of looking at it… Nice one!

Actually, from what I’ve read the size and shape of the rock is certainly one important criterion in why a rock would have been chosen as sacred. Others would include location, sense of presence and historical association…

Incidentally, it’s worth noting too that living rocks are written into the national anthem and that the lines contain the idea of rocks growing and maturing… Here’s the Kokinshu verse on which the lines are based:

May a thousand years,

eight times a thousand, be your life

until the smallest pebble grows into a rock

covered in moss!