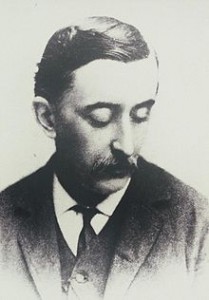

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) in a typical pose to avoid his blank eye being seen

Honeymoon period

On my recent visit to Izumo, where the kami of Japan are presently gathered, I took the opportunity to make a literary pilgrimage to the home of Lafcadio Hearn. Though not well-known abroad, he is treasured in Japan for his sympathetic accounts of the country not long after its opening to the West. A curious figure, he was the son of a British officer and a Greek woman, raised in Ireland, attended boarding school in England, then went to the US where he carved out a colourful career in journalism before heading for Japan just before his fortieth birthday.

Hearn arrived in 1890 and spent fifteen months in Matsue, ‘province of the gods’. in a classic case of what anthropologists call the honeymoon period, he was enchanted by everything he saw. A hundred years later when I myself arrived in Kanazawa, further north along the Japan Sea, I was similarly entranced by a Wonderland where all was bizarre yet charming. Like a second childhood, one has to learn from scratch to understand customs that are alien and a language that is indecipherable.

“Elfish everything seems,” wrote Hearn, “for everything as well as everybody is small, and queer, and mysterious: the little houses under their blue roofs, the little shop-fronts hung with blue, and the smiling little people in their blue costumes. The illusion is only broken by the occasional passing of a tall foreigner, and by divers shop-signs bearing announcements in absurd attempts at English. … It then appears that everything Japanese is delicate, exquisite, admirable—even a pair of common wooden chopsticks in a paper bag with a little drawing upon it… Curiosities and dainty objects bewilder you by their very multitude: on either side of you, wherever you turn your eyes, are countless wonderful things as yet incomprehensible.”

Collector of tales

Hearn’s house stands opposite the castle and gives a sense of the lifestyle he so enjoyed. The former house of a samurai, his home had a charming little garden with a pond mentioned in his writings. Here the odd-looking Hearn found himself. He settled down in marriage, and when he naturalised he took his wife’s family name, calling himself Koizumi Yakumo (the second name, ‘eight-fold clouds’, is that of the local area, indicative of his attachment).

Hearn’s house in Matsue, Shimane prefecture

Hearn had been drawn to Japan by a book of Percival Lowell, The Soul of the Far East (1888). Here in Matsue he was delighted by the spiritual devotion of the locals, learning eagerly of their religious beliefs. It’s said his fascination was fostered by having been told of Irish legends as a child by his Connaught nanny.

I once went to a talk by Hearn’s great grandson, Koizumi Bon, who mentioned the similarities of Celtic and Japanese animism. The circle of the Irish cross, for instance, is a remnant of ancient sun worship; animal familiars serve the gods; there is an Irish equivalent of Setsubun, when devils are driven out to ensure happiness in the coming year; and the Irish wishing tree is hung with cloths in similar manner to the way Japanese hang their fortune slips to trees.

In Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894) Hearn goes into some detail about local traditions, and the descriptions are fascinating because of their record of the past. Some of the customs remain; others have vanished down the vortex of history.

**********************

“I see men and women descending the stone steps of the wharves on the opposite side of the Ohashigawa, all with little blue towels tucked into their girdles. They wash their faces and hands and rinse their mouths—the customary ablution preliminary to Shinto prayer. Then they turn their faces to the sunrise and clap their hands four times and pray.

From the long high white bridge come other clappings, like echoes, and others again from far light graceful craft, curved like new moons—extraordinary boats, in which I see bare-limbed fishermen standing with foreheads bowed to the golden East. Now the clappings multiply—multiply at last into an almost continuous volleying of sharp sounds. For all the population are saluting the rising sun, O-Hi-San, the Lady of Fire—Ama-terasu-oho-mi-Kami, the Lady of the Great Light.

‘Konnichi-Sama! Hail this day to thee, divinest Day-Maker! Thanks unutterable unto thee, for this thy sweet light, making beautiful the world!’ So, doubt-less, the thought, if not the utterance, of countless hearts. Some turn to the sun only, clapping their hands; yet many turn also to the West, to holy Kitzuki [Izumo Taisha], the immemorial shrine and not a few turn their faces successively to all the points of heaven, murmuring the names of a hundred gods; and others, again, after having saluted the Lady of Fire, look toward high Ichibata, toward the place of the great temple of Yakushi Nyorai, who giveth sight to the blind—not clapping their hands as in Shinto worship, but only rubbing the palms softly together after the Buddhist manner. But all— for in this most antique province of Japan all Buddhists are Shintoists likewise—utter the archaic words of Shinto prayer: ‘Harai tamai kiyome tamai to Kami imi tami.”

**********************

The garden in Hearn’s house in Matsue of which he wrote so graphically

Shinto as a key to understanding Japan

I’ve always felt ambivalent about Hearn, for he clearly idealised Japan as means of escaping from a West where he felt out of place. By contrast his friend Basil Hall Chamberlain, author of Things Japanese (six editions 1890–1936) viewed Japan with scholarly detachment. Unlike Hearn, he was fluent in Japanese and balanced his sympathetic accounts with some harsh comments. Yet it is the romanticist’s vision which has won the wider readership, for the power of imagination invariably trumps dull reality. ‘When legend becomes fact, print the legend,’ says a character in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Vallance.

Over time Hearn was to become well-versed in Shinto, and to see it as fundamental to an understanding of the culture as a whole. Japan, An Attempt at interpretation (1904) remains a classic of its kind and even now, despite a century of dramatic changes, the insights are compelling. Hearn manages to shed clarity on the vague and often contradictory mix of Japanese belief systems. He only lived in Matsue a brief fifteen months, before going on to Kumamoto and Tokyo University. It was Matsue though that shaped his attitude to Japan. It was here in ‘the province of the gods’ that his love of Japan’s spiritual life was first fostered.

**********************

“The real religion of Japan, the religion still professed in one form or other, by the entire nation, is that cult which has been the foundation of all civilized religion, and of all civilized society,—Ancestor-worship. In the course of thousands of years this original cult has undergone modifications, and has assumed various shapes; but everywhere in Japan its fundamental character remains unchanged. Without including the different Buddhist forms of ancestor-worship, we find three distinct rites of purely Japanese origin, subsequently modified to some degree by Chinese influence and ceremonial. These Japanese forms of the cult are all classed together under the name of “Shinto,” which signifies, “The Way of the Gods.” It is not an ancient term; and it was first adopted only to distinguish the native religion, or “Way” from the foreign religion of Buddhism called “Butsudo,” or “The Way of the Buddha.” The three forms of the Shinto worship of ancestors are the Domestic Cult, the Communal Cult, and the State Cult;—or, in other words, the worship of family ancestors, the worship of clan or tribal ancestors, and the worship of imperial ancestors. The first is the religion of the home; the second is the religion of the local divinity, or tutelar god; the third is the national religion.”

**********************

View towards Hearn’s house in Matsue, where he first learned about Japan’s ancestor worship

Glimpses on Unfamiliar Japan can be read online here. Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation can be found here.

good post, John. LH was part of my early turn-on-to Oriental traditions, and he remains an evocative figure for all us long-term Asia-expats…

See the article on the Open Mind Of Lafcadio Hearn at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/fa20101105a2.html

Thank you for pointing that out. I like the final quotation very much…