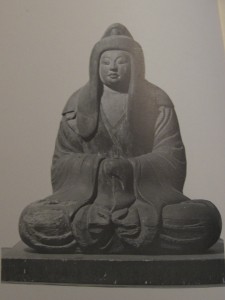

Male and female kami (Muromachi Period)

Last week I went to an exhibition of kami statues at Otsu History Museum. The statues came from Shiga prefecture – ‘land of gods and buddhas’ – together with mandala and photographs of Hiyoshi Shrine’s Sanno festival. There were not only statues of kami in human form, but even as monkeys. It all exemplified the rich and complex world of Shinto-buddhist syncretism.

Before the eighth century there were no representations of kami. Not surprising, really, since they were originally conceived as formless. But the arrival of Buddhism with its powerful array of sculpture proved seductive. Could not kami be similarly portrayed?

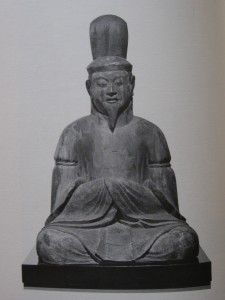

With Buddhist priests worshipping kami as temple protectors, it was only a matter of time. By the 9th century, two distinct styles had emerged. One showed the kami dressed as courtiers (as above), inspired by ancestor worship and embodiment of the dead. The other showed the kami as Buddhist priests (on the right).

Kami as Buddhist priests?!

There were Shinto-Buddhist syncretic practices as early as the seventh century, with Buddhist priests worshipping kami as protective guardians of their temples. The priests came to see the kami as seekers after enlightenment and prayed for their salvation.

For Buddhists all things have buddhist nature, so it was natural to assume that kami do too. As Japanese manifestations of the universal principle, they were recognised by priests as being closer to the people than the more remote figures of Buddhism. In one famous example, Ippen, founder of the Ji sect of Buddhism, received confirmation of his faith from the kami at Kumano Shrine.

When it came to making statues, the kami were often pictured as monks, showing their true essence. Sogyo Hachiman, protector of the giant Buddha at Todaiji, is the most famous example. The statues had a numinous power deriving from the tradition of sacred trees and a sense that the tree-spirit had entered into the wood. Compared with Buddhist sculpture (butsuzo), there was greater respect for the material. Statues were carved from a single wood block, with occasional add-ons for feet or hands.

Through a special ceremony (called kanjo), the statue could be imbued with the spirit of the kami to become a sacred object. In this case it would serve as ‘goshintai‘ (the spirit-body) of the kami and be kept out of sight in the shrine’s honden. Sometimes too there was an eye-opening service in the Buddhist tradition, in which the eyes were painted in to denote spiritual awakening.

With deconsecration of shrines in the Meiji era, many of the statues were lost or stored away. Several found their way to foreign museums. Some were even retained by Buddhist temples. Though rarely if ever seen at shrines nowadays, the shinzo statues remain a graphic depiction of how Japanese visualised their kami.

Female kami at Matsuo Taisha in Kyoto

Male deity at Daishogun Hachi Shrine, Kyoto

Information taken from Shinzo: Hachiman Imagery and its Development by Christine Guth Kanda (Harvard Uni. Press, 1985)

From A.J. Dickinson…

Shinzo

Feeling the formless

Permeating the green

Carving the wood

Curving the sheen