White horses

White horses

What is it with white horses? Near my home town of Oxford, there’s one that was scoured into the chalk hill some 2000 years ago. Since ancient times commanders, kings and emperors have liked to ride white horses. And here in Japan white horses were once offered to shrines as gifts for the kami.

Horses were special because they were restricted to the élite. For ordinary people horseriders were looked up to – literally. There was something godlike about them, for they were insulated from contact with the earth unlike mere mortals.

It was the horseriding élite who after death were honoured as tutelary kami, and the horse was seen as a sacred mount which transported them from one realm to the other. On the continent it had been the custom to sacrifice horses and cows to the gods. Whether this was transmitted to Japan is disputed, but the practice that evolved in Japan was to offer horses as gifts. “Horses were viewed as agents for bearing the kami since ancient times,” says the Kokugakuin encyclopedia, “and it was customary to present a horse to the kami as an expression of gratitude when making a vow or entreaty at a shrine.”

But why white? White is the colour of purity, and as such treasured by Shinto. Priests wear white robes; the paper shide to mark sacred space are white; the gohei into which kami descend are white.

White is also a colour of distinction, and in East Asian shamanism anything in nature that is distinctive may be a sign of divine possession. It’s why trees and rocks and mountains of distinctive shape are signalled out as sacred. White and albino animals too.

Substitutes

At some point in history it became prohibitively expensive to keep presenting white horses to shrines, and someone had the bright idea of presenting a clay model instead. An unreal horse for an unearthly spirit.

The practice caught on, and over time spread to the offering of statues and two-dimensional representations on large wooden boards. The idea may have originated from depictions of the animals in the Chinese zodiac, introduced from the continent. Already by the Nara period wooden plaques with horse pictures were being donated to shrines. As sacred art, the paintings were done by leading artists (in a later age Hokusai was to paint them).

By the Muromachi period, subjects other than horses were being depicted, though the practice was still restricted to the élite. The large plaques were exhibited in a special hall (emado). It was only in Edo times that small wooden votive plaques became widespread, following the custom of ordinary folk to hang up religious emblems. People wrote their names on the back, sometimes adding wishes of their own.

Originally the wooden tablets were used as prayers against disease and for good crops, but gradually the scope widened. They were handpainted by local people, who created their own designs. Though the practice flourished in Meiji times, there came a downturn by the mid-twentieth century as modernisation swept aside the old ways.

Postwar developments

Postwar developments

After WW2 one particular artist had the bright idea of adapting silk screen technology and was able to mass-produce ema. The idea caught on, and with the reduction in price came a revival of popularity. Now you cannot fail to find them in abundance at any large shrine. Typically they cost from Y600–Y1000 each.

From white horses, the subject matter spread to myth and local folklore, even sometimes to altogether profane matters. Shrines came up with their own original creations, as in the example from Fushimi Inari on the left where you fill in the fox’s face yourself.

It’s said that the shrines get a 100% mark-up on the ema they sell, and that one brand can sell up to 100,000 a year. Nonetheless some priests are sceptical of whether it constitutes real religious activity, claiming it is more akin to making wishes at a wishing-well.

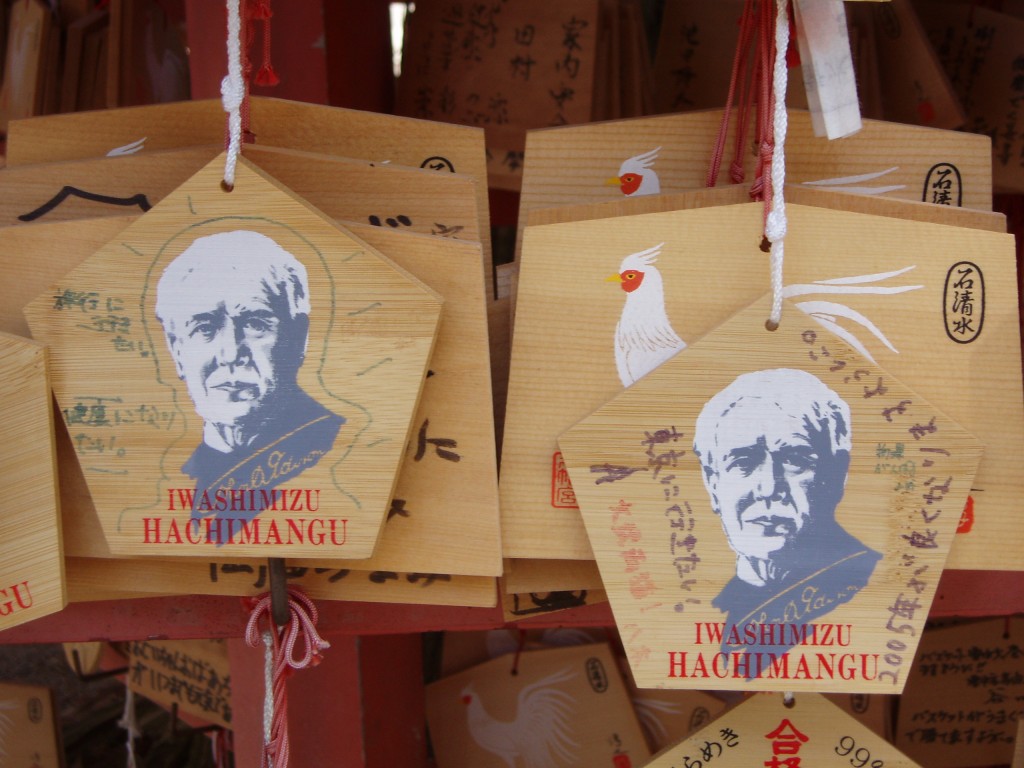

For some years I’ve been collecting ema, and I must have acquired nigh on two hundred by now. Amongst the collection is one with the face of Thomas Edison, the American inventor. Was he a Shintoist? No, but the bamboo he chose for his lightbulb happened to come from near Kyoto because it was of a particularly tough strand suitable for use as a filament. The American inventor now finds himself immortalised in the ema of Iwashimizu Hachiman-gu. From a living white horse, offerings to the kami have transmogrified into pictures of a dead white male!

White horse at Kamigamo Jinja, one of the few shrines still to keep a live horse

Horse statue at Izumo Taisha, almost as good as the real thing

Here the mount for the kami is itself getting a ride!

White fox ema at Fushimi with personalised faces

Many ema show animals of the Chinese zodiac year

Some ema have an original shape

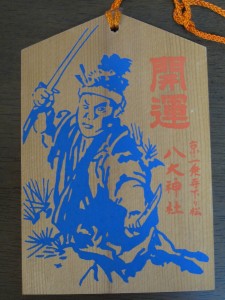

Some ema tell of the shrine folklore (this depicts the samurai hero Musashi)

Some ema are simply cute, in the manner of Hello Kitty

Information for the above article draws on Ian Reader ‘Letters to the Gods: The Form and Meaning of Ema’ in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1991 (vol.18/1)

Ema can be syncretic and are sold at temples too. This one depicts the Buddhist hell.

Some ema are puzzling: the priest at this shrine told me there was no connection with Daruma at all.

Some ema are magical (the pentagram here was the symbol of Onmyodo Wizard, Abe no Seimei)

Some ema have manga-style prayers by a new generation of shrine-goers.

I have enjoyed the Iwashimizu Hachiman-gu in Yawata for many years, John. The last time I was there, they still kept a live white horse that grabbed my jacket in its mouth and picked me right up off the ground! Hachiman-sama is not one to fool with.

Also, I love the back of the Edison ema: 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration. It sounds very Japanese.

Hi John…

Thanks for that… you’re right about the quote. It does sound very Japanese! Also the live horse at Iwashimizu Hachiman is one of the two I know about in the Kyoto region, together with the Kamigamo horse. I read once that there were only a handful of shrines left which still keep white horses, but I’m not sure where the others are, apart from Ise.

Excellent work. A few notes. The horse is one of the symbols of dominion of the “Ideal King”

(Kyōryōrinjin 教令輪身 or Kyōryōjō-ō 教令聖王), known as Chakravartin in Sanskrit.

Batō Kannon 馬頭観音

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/kannon.shtml#batou

Horse-Headed Kannon. Protector of Animals. He is distinguished by the white horse’s head that he wears like a crown. Batō Kannon appears in the Mahāvairocana Sūtra (Jp. = Dainichikyō 大日經; composed sometime in the 6th / 7th century AD) and other tantric texts. He is thus a member of the esoteric pantheon. Batō is also one of the Six Kannon. In this latter role, Batō protects those reborn in the animal realm (chikushōdō 畜生道), a realm characterized by stupidity and servitude. Effigies of the Six Kannon began appearing in Japan in the early-mid 10th century onward and were prayed to for the welfare of the dead. The scriptural basis for the six can be traced back to a late 6th-century Tendai text from China, although Batō was not part of the original six but rather inserted some four centuries later. See Six Kannon for details (at my web site).

I think that calling modern, mass-produced ema “profane” is a big mistake, just the same as Ian Reader, Helen Hardacre, etc. calling the Edo-era brothels at Ise Shrine “profane” is a mistake. What are they profane in comparison to? In the latter case, the answer is clearly Christianity. In the case of this blog, there is still no transition from sacred to profane to be made. In olden days, rich lords presented horses to the shrine. Now we are a little short on rich lords, but every tourist who comes to a shrine can do it a favor by buying an ema. I don’t know what your profaneness refers to, but no matter what is put on the face of the ema, the idea of an offering to the shrine does not change.

Hello Avery…

I see your point, but the sentence in question actually says that the subject matter turned profane, not the offering of ema. The dictionary definition of profane says ‘secular rather than religious; not initiated into religious rites.’ I think one could reasonably claim that an ema depicting, say, Thomas Edison, is certainly not religious in subject matter and hence profane. (The offering of it on the other hand may well constitute a religious rite.)

I see that the Edison ema is pentagonal. Is it, by any chance, an exam success ema? They’re often pentagonal because the Japanese for “pentagon” and “pass [an exam]” sound very similar. If so, it’s even somewhat appropriate.

Hi John,

Two little bits of trivia to add to the horse and ema discussion. There is an Ema museum in Gion at Yasui Kompira gu. One other interesting point about horses and shrines is that some shrines, like Kibune in the north of Kyoto have both a black and white horse. The black horse will get you rain, and the white one will help you to stop it. The horses at Kibune are not live but very energetic statues.

My Popsie recently brought me 2 paintings from Japan of 1 white horse facing right and a brown horse facing left.

He heard that they should be facing each other on either side of an entrance door, is this correct?

Good day, Kai… In rainmaking ceremonies in the past they used white and black horses, so perhaps that is the reference being made in the paintings you have. I wonder if they are done traditional style on a large ema board, or are they simply modern paintings? In any case I hadn’t heard about them being placed either side of an entrance door, though that is much in keeping with the two guardian figures at the entrances to shrines and temples. It’s a nice idea if you can get them to fit… emissaries ready to transport guests into another world, so to speak.

Hello, Kai again… Thank you for sending photos of the two paintings. I see they’re done on paper from a woodblock, and they’ve been recently framed. They’re from the Hida area, famous for its horses and horse ema. Apparently it used to be the custom to hang a paper horse picture in the entrance (genkan), as you suggest. However, I’m unsure whether pairs were hung in this way. In the shrine they would presumably have appeared on ema boards alongside each other. As such I would say they’d make a fine pair of paintings hung on an interior wall…