I recently heard a talk by Peter Watson, author of a book entitled The Great Divide about the way the New World of the Americas was divided from the Old World of Europe and Asia for some 16,500 years. It was the first time in history for a substantial population to be cut off in this way, which makes it interesting to study the cultural differences that evolved. Here’s the timeline…

c.180,000 BC – Early humans develop in Africa

c.125,000-80,000 BC – Migration out of Africa

c. 20,000-16,000 BC – Movement into Siberia

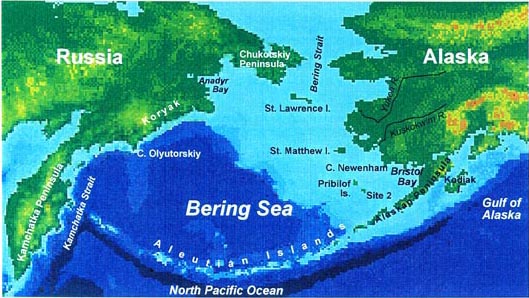

c. 16,000 BC – Movement over the land bridge (now Bering Strait) into America

c.15,000 BC – Ending of the Ice Age with sea levels rising a massive 400 feet. Bering Strait fills with water.

Courtesy of Vera Alexander

As a result of this, the New World became cut off from the Old Asian one. Despite this, the New World immigrants are linked genetically to East Asians through features such as the Mongol spot, and culturally through language similarities and shared myths.

Izumo’s land-pulling myth

One of the results of the ending of the Ice Age was the impression it left in the myths of peoples living close to the sea. On both sides of the Pacific there are so-called ‘Land Rising Myths’ in which the land arises mysteriously out of the sea. A typical example is of the land being torn off from somewhere and dropped by birds. Such stories are found on the Pacific rim, but nowhere else according to Peter Watson. In this respect I couldn’t help thinking that the Izumo ‘land-pulling myths’ might belong to the same group.

In the land-pulling myth (or kunihiku), one of the local deities at Izumo thinks the land is too narrow and pulls over land from four places that he can see across the Japan Sea, including the Korean peninsula. These bits of land are then attached to the Izumo region (now Shimane Prefecture), thus expanding the territory and pushing back the sea.

Part of the Izumo coast

The traditional explanation of the myth is that the bits of land pulled over are connected through immigration with the Izumo region. Thus the land is symbolic of the people crossing over in Yayoi times. However, I can’t help wondering if there is not a folk memory too of the land appearing out of the sea in the distant past. Could the miraculous appearance of new land after the Ice Age underlie the Yayoi myth?

Religious developments

Another aspect on which Peter Watson dwelled was the difference between New World and Old World religious development. Here he was mainly contrasting the ‘supplicatory’ religions of Europe, based on a secure agricultural cycle, with the ‘propitiatory’ religions of S. America where natural disasters were common and life was more fragile. In a land of earthquakes, tornadoes, famines, El Nino etc, he suggested, the notion of offering sacrifices to appease the gods was more likely to arise.

In this sense it would seem Japan belongs more to the New World than the Old, because of the link of Shinto with the precariousness of life in a country prone to natural disaster. However, given the links of Japan with East Asian religion in general, I wonder if Peter Watson’s theory stands up.

He also suggested that there might be a link between the pastoral nomadic culture of the Old World and the development of monotheism. This was largely through the dynamic instability caused by horse culture, which provides movement and competition between neighbouring tribes. Through conflict came the impetus to innovation, leading to the bronze age, iron age and eventually, he suggested monotheism. And the idea of an abstract God had developed who was knowable through his works led to scientific exploration and greater curiosity about the world. The result was that by 1492 it was the Old World which discovered the New, and not vice versa.

It’s a theory that makes one think of Japan, with its pattern of rice-growing communities nestled in the country’s many small river basins. Japan’s “civilisation” was very slow to develop by comparison with the mainland, and the country lagged behind China by some thousand years. Could it be linked with the lack of dynamism that came with the horse-riding cultures of the great plains, one wonders? Did rice-growing communities foster the kind of status quo stability that enabled feudalism to last right up to 1868?

Food for thought…

Orderly but static harmony?

Leave a Reply