Extract from my book In Search of Japan’s Hidden Christians, published today in the US, the UK and Japan…. (For Part One of this article, see here.)

************************************************************

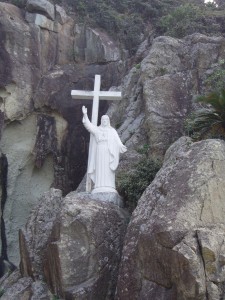

Cave on the Goto Islands where Hidden Christians hid from persecution

As my journey was nearing its end, I happened to talk to a Japanese woman who told me she prayed every evening before she went to bed to kamisama (a respectful name for god). Which kamisama, I asked, in the analytical manner that characterizes Westerners. “The kamisama in heaven,” she answered as if it was self-evident. But what heaven? I persisted, bluntly. Only when pressed did she even consider the matter. Her kamisama, it turned out, was a nameless composite embracing Jesus, all the buddhas and the whole multitude of Shinto kami. It was one in all, and all in one. No singular, no plural.

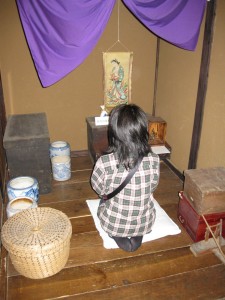

The underlying unity of “the masks of God” was detailed most famously by Joseph Campbell, who in an interview with Bill Moyers said that “Every god, every religion, every mythology is true in this sense. It is true as metaphorical of the human and cosmic mystery.” The Japanese long ago realized that the divine comes in multiple guises, and in consequence developed a natural inclination to syncretism. It is exemplified by the Hidden Christians of Hirado, who not only kept their closet gods but maintained a kamidana (kami shelf), butsudan (Buddhist altar) and worship of house spirits. In reverting to a combinatory belief, they were reverting to cultural type.

Recreation of a Hidden Christian altar from Edo times in Ikitsuki Museum

The worldview was formed in ancient times by customs and practices that have since come to be called Shinto, and I’d reached the conclusion that here lies the key to an understanding of Japanese culture. Not in Zen, as D. T. Suzuki had it, but Shinto. A Hidden Christian woman whom Christal Whelan interviewed in her research on the Goto Islands illustrates the point. In an attempt to convert her, a Catholic priest had been giving her Bible lessons. “What a strange book,” she said, “I understood nothing.” By contrast, Shinto which derived from the seasonal round of agrarian life, made perfect sense to her. It also provided communal continuity, for it was what the ancestors of her ancestors had practiced.

My journey had finished, but as T. S. Eliot memorably put it, “The end is where we start from.” A new journey beckoned, one that I hoped would take me to the country’s shrines and the circular mirror that stands at their core. In the magic mirror of the Hidden Christians was concealed a secret image of the crucifixion: within the mirror of Shinto lies the soul of Amaterasu. They are two images of the divine, one universal and one particularist. One speaks of a creator God, the other of an ancestral deity. One is transcendent, the other animist. They seem to have little in common, to epitomize an unbridgeable gap whose consequences were evident in the martyrdoms and persecution of Edo times. The genius of the Hidden Christians was to reconcile the two. As they pass into history, their legacy surely deserves to be cherished.

**************************************************************************

Today it’s estimated that there are fewer than 1000 practising Hidden Christians, concentrated on the island of Ikitsuki off Hirado and in Goto. Most are elderly, there are no more baptisms being carried out, and no successors willing to take over hereditary duties. In all probability this is the end of the line for the tradition.

Bastian's hut at Sotome, where an influential Hidden Christian leader stayed in the woods in the 1640s

It’s nice we can leave comments on this site. “The end is where we start from”– you will find this idea reflected in Hailstones new book, released this coming Thursday. Otanoshimi ni. It’s the first time I have encountered this quote. Bastian’s Hut reminds me of Thoreau’s at Walden Pond, although their purpose was ostensibly different.

Thanks for the thoughts. In terms of huts, it’s Kamo no Chomei’s that always reminds me of Thoreau… both were not quite as cut off as they would like us to believe, for one thing, and both went to experience living in nature. Poor old Bastian must have been living in constant fear of when the shogunate authorities were going to come and get him. Considering what they were likely to do to him, it’s an incredibly brave way to live.

Good luck with the Hailstones book launch, and I look forward to seeing the haiku…

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting!

I certainly enjoyed reading it, and I will remember to bookmark your blog and definitely will come back in the future. I want to encourage continue your great posts about Shinto, have a

nice holiday weekend!