Arne Kalland, professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo, here responds to an article by Aike Rots on Shinto’s sacred forests (see Part One.) For the full article, click here.

*******************************************************************************************************

Nature as Japaneseness

The Japanese national essence

Nihonjinron [the debate about Japaneseness] comes in many wrappings but a basic premise for our discussion is the notion that an aesthetic appreciation of nature can be ascribed to religion and that religious aestheticism is translated – at least before the dawn of westernization – into behaviour. Hence there is a widely held notion that the Japanese both love and live in harmony with nature.

Another related premise is natural determination. The intellectual Shiga Shigetaka (1863-1927) tried already in the middle of the Meiji-era (1868-1912) to define the Japanese “national essence” (kokusui) as a product of climate, topography, soil, plant- and animal life and the interplay between these factors. The fundament was laid for ideas both about a unique Japanese nature and about a unique relationship between the Japanese and nature, ideas that played important roles in the ultra-nationalistic ideology that emerged in the interwar years.

One should, perhaps, expect that such nationalistic nature ideology would disappear with the war defeat. Eco-nationalism is no longer part of the state ideology, at least not officially, but there are still many voices claiming that there exists a unique harmony between the Japanese and nature, and that this relationship rests on particular qualities of nature in Japan.

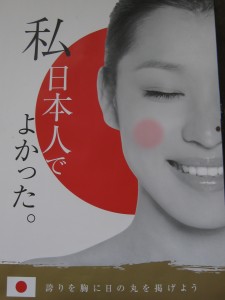

It's good that I'm Japanese, says this Shinto poster.

The archaeologist Yasuda Yoshinori, professor at the Nichibunken (the International Research Center for Japanese Studies) claims that the special Japanese relation with nature goes back to a 12,500 years old “forest civilization”. Since then the Japanese “have kept cultural and social traditions that excel in letting nature live and thus letting ourselves live in it”.

Moreover, he believes that cultures based on human exploitation of nature – as Christianity allows – destroy forests, and he blames Christianity for being responsible for the expansion of the “civilization of deforestation” and for invading and ruining primitive and peaceful civilisations based on harmony between human beings and nature.

Only Japan avoided this destruction thanks to her insular isolation, and animism consequently survived in the form of Shinto almost to the present. However, after 1970, if we are to believe Yasuda, the Japanese have deserted animism and its forest deities for computer deities, with serious environmental degradation as a result.

It is within such a context we must understand the emergent ecological awareness of Jinja Honchō and other Shinto organizations. They have discovered the legitimacy implied in the religious environmentalist paradigm. Rather than being associated with a discredited imperial system of pre-war years, Shinto ideologues and scholars can now attach themselves to an honourable global environmental discourse. But, as stated by Rots, the importance of shrine forests is symbolic and ideological rather than merely ecological, and by expressing their environmental messages in the rhetoric of nihonjinron, they may once more be accused of nationalism.

Rising sun: nature worship or patriotic symbol?

excellent!