Could you tell us about your background?

Could you tell us about your background?

At Waseda University I studied the politics of forest conservation and did an internship in Kenya. It made me think about the role of culture and how to make use of traditional ways. How did Japanese ancestors look after the land, for example? Then I worked for a private foundation in conserving nature and it led me to the traditional style of revering nature.

Now you want to become a priest. How did that come about?

I wasn’t thinking about that really, but it happened by chance. Fate, you could say. When I was visiting a shrine called Kamikura Jinja in Wakayama, there was someone meditating and playing shinobue (a Japanese flute) there. I got to talk to him and he found I was interested in spiritual things. It turned out he was head priest of a small shrine, and he thought our meeting must be meaningful because it happened at the time of the full moon. In the end he invited me to work at his shrine as a kind of trainee.

You’re not from a priest’s household, are you?

No, I’m not. It’s a bit unusual, perhaps. But I hope to find my own way to combine my feeling for nature with worship of kami if I can.

Meditating and playing flute (shinobue) at Kamikura Jinja

What’s your plan for the future?

I’d like to be involved with an NPO or some foundation doing nature conservation. And I’d like to remind people of our roots and how to live in harmony with nature. We used to have lifestyles that embraced satoyama and okuyama. Satoyama was sustainable use of woodland. Okuyama was a place that was left untouched because it was the realm of the kami.

There was a hill I visited once with an iwakura (sacred rock), and everything beyond it was left just as it was, because it was a realm of the spirits. We need to remember that kind of tradition, I think.

As someone drawn to the Schumacher College, which presents an alternative to conventional thinking, your environmental sympathies put you at odds with the Shinto establishment which tends to be rather right-wing. Is that a problem, do you think?

No, I don’t think so. People in Shinto are conservative, but they are open too. And I think from now on people with my kind of thinking will become more common. Perhaps it’s a different kind of generation.

Thanks for your time, and here’s wishing you the very best for the future. Shinto – and Japan – needs more young people like you !

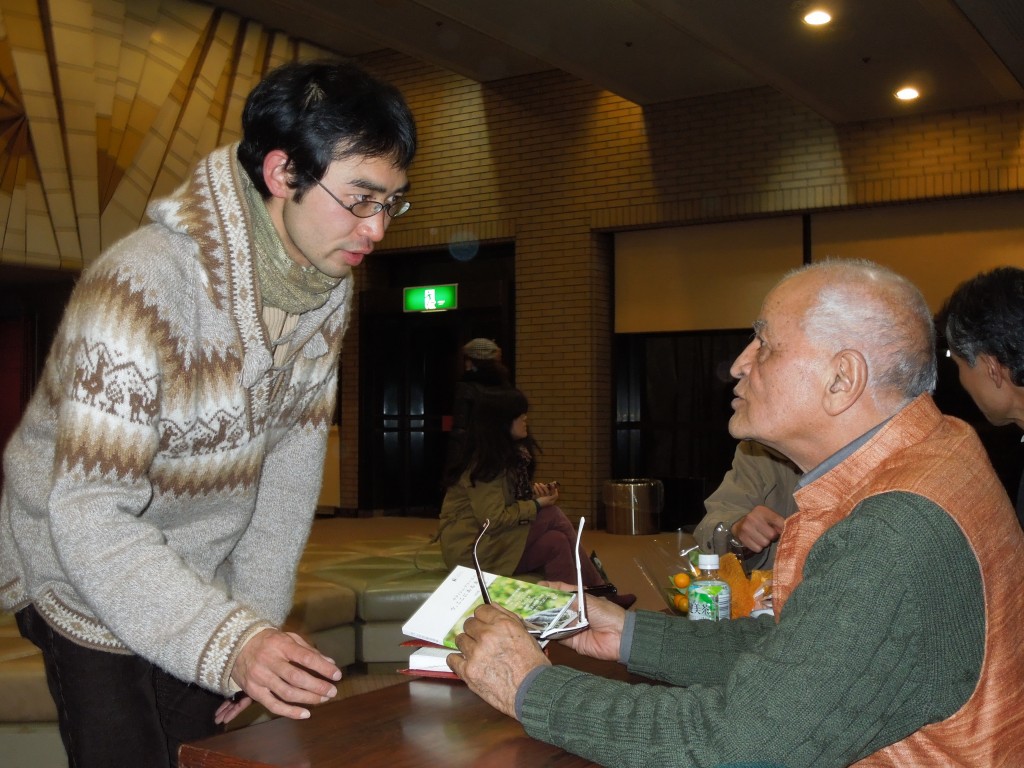

Exchanging ideas with environmentalist Satish Kumar of Schumacher College

Leave a Reply