In a recent article in the Daily Yomiuri, naturalist and anthropologist Kevin Short has written of the role of the fox in Japanese folklore. For Shinto, the fox looms large in the cult of Inari, and in The Fox and the Jewel (1999) Karen Smyers has written at length of the peculiar appeal of this liminal animal.

*******************************************************************************************************************************************

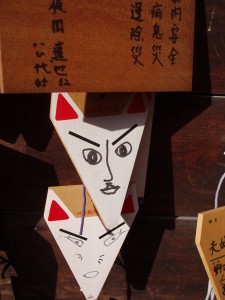

Foxes are among the great perennial stars of Japanese folklore. To begin with, they are considered to be familiar spirits serving the immensely popular rice deity Inari. A set of two stone foxes stand watch in front of every Inari shrine.

Foxes are among the great perennial stars of Japanese folklore. To begin with, they are considered to be familiar spirits serving the immensely popular rice deity Inari. A set of two stone foxes stand watch in front of every Inari shrine.

Some folklorists believe that foxes became associated with rice farming because of their role in controlling mice, hares and other agricultural pests. In the past farmers would even leave out food to attract foxes to their rice paddies. Foxes are thought to be especially fond of abura-age, thin slices of deep-fried tofu soy bean paste. Pockets of abura-age stuffed with rice are known as Inari-zushi.

In contrast to this favorable agricultural image, foxes have also been traditionally imagined as clever tricksters and shape-shifters. These yo-gitsune can be encountered in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Like cats and many other Japanese fairy animals, their magical powers grow stronger with age. After living for a century or two, yo-gitsune become able to possess people, causing illness or insanity, and also to temporarily shape-shift into incredibly glamorous women. Stories abound of men falling hopelessly in love with and marrying these “foxy ladies.”

In one famous story, a 10th-century nobleman saves a fox from a mob bent on killing it for its liver. A few days later, a beautiful woman mysteriously appears at his door. They fall madly in love, get married and have a son. Three years later, the woman suddenly disappears, leaving a note explaining to her husband that she was really just the fox whose life he had saved. Their son grows up to be Abe no Seimei, the famous Onmyoji Yin-Yang wizard who protects the imperial court and the capital city from all sorts of wicked spells and disasters.

After living for a full millennium, fairy foxes may attain a formidable style with nine tails. Nine-tail foxes, or Kyubi no Kitsune, are of Chinese origin, but have also been active in Japan as well. During the Edo period (1603-1867), motifs depicting heroes ridding the land of these often ill-tempered nine-tail foxes were widely adopted into traditional theater, literature and art.

Until quite recently, mental illnesses and emotional instability were frequently attributed to possession by fox spirits, especially in isolated rural villages. Even more frightening, there are families, called tsukimono-mochi, which are rumored to keep tiny fox spirits in vases or bamboo tubes. These spirits can be sent out on various missions, such as searching for gold or treasure, stealing, spying on people, or just causing all sorts of trouble and misfortune. The secrets of caring for and controlling these fox spirits, or in some cases similar dog or weasel spirits, are passed down from generation to generation among women of the household. Families which are rumored to possess fox spirits are feared and shunned.

Another peculiarity of fairy foxes is that they tend to emit strange lights at night. One very famous spot for kitsune-bi fox-fire is the Inari shrine at Oji in Kita Ward, Tokyo. Every New Year’s Eve foxes from all over the Kanto region are believed to assemble here under an ancient hackberry tree. The local farmers predict the yields of the coming season’s crops by the number of glowing lights they count.

Japan’s fox lore was derived predominantly from China, although the Japanese did add a “divine” connection between their fox and their local kami of rice, Inari. This gives the fox a dual character in Japan — both evil and sacred. This dichotomy is not found in China, where the fox is mostly evil. The fox’s divine connection to Inari is hard to discern, but the most accepted theory today involves Japan’s Yama-no-Kami 山の神 (mountain deity) and Ta-no-Kami 田の神 (rice-paddy deity). In Japanese folklore, the mountain kami was believed to descend from its mountain residence in the winter to become the rice-paddy kami in the spring, residing there throughout the growing season. After the fall harvest, the deity returned once again to its winter home in the mountains. All this probably took place at the same time that foxes appeared each season. As such, the fox naturally became known as the messenger of Inari.

In Japan, white foxes are closely connected with Inari, Benzaiten, Dakiniten, and the Tengu. Foxes appear often, along with white snakes, in artwork related to Benzaiten-Dakini. In fact, snakes, dragons, and foxes share much overlapping iconography in Japan — each of these supernatural creatures is, for example, associated closely with the wish-granting jewel.

Foxes were much persecuted in old China, mostly by smoking them out of their burrows (often located in caved-out old graveyards). This prompted Chinese authorities to forbid smoking foxes out of graveyards. Similar laws were later enacted in Japan during the reign of Emperor Mommu 文武 (697-707). Promulgated in 702 in Section VII of the Zokutō Ritsu 賊盗律 (Laws Concerning Robbers), these edicts warned against “smoking foxes and tanuki (Jp. = Kori 狐狸) out of graves.” The subject of the Japanese fox is so voluminous that Lafcadio Hearn described it as “ghostly zoology.” For much more on these fascinating topics, see:

Fox Lore in Old China http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/tanuki.shtml#origins

Fox Lore in Old Japan http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/tanuki.shtml#OldJapan

Comparing Fox in C & J http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/tanuki.shtml#TableOne

Benzaiten, Dakin, & Foxes http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/benzaiten.shtml#Dakini

Kitsune are not “fairies”. Neither are any other of the creatures called “fairy animals”. They are youkai. The only similarity between fae and youkai is that they are spirits/entities that have been seen to live on Earth, and they are supernatural beings. Nothing else in their lore is similar.

Youkai do not have a “Faerie” land nor do they have the same kind of etiquette that fae have. They do not exhibit the same weaknesses, nor the same behaviors or tastes, other than the fact that some specific types of Youkai are tricksters. Youkai are not fairies, youkai are youkai.

Thank you for that useful input…