Kyoto's Daimonji, a signal to the dead (courtesy of Aaron Williamson)

Today is Obon in Kyoto, when ancestral spirits are welcomed back home before being sent off with a grand fire ceremony called Daimonji, about which I’ve written previously. (See here.) The festival appeals to the syncretic sentiments of the Japanese, as can be seen by the Daimonji fires not only forming references to Buddhist teaching but to a Shinto torii too.

It’s sometimes said that ancestor worship is the true Japanese religion, underlying both Shinto and Buddhism. It’s such a strong component of national consciousness that Buddhism has become largely a funereal business centred around prayers at the family altar (butsudan) to deceased family members. Moreover, I’ve seen it argued that rather than a nature religion, Shinto is primarily a religion of ancestor worship.

When people think of the roots of ancestor worship, they often think of East Asia and China in particular. It’s not realised though that Britain too most likely had a flourishing ancestor worship of its own, probably around the same time as ancient China.

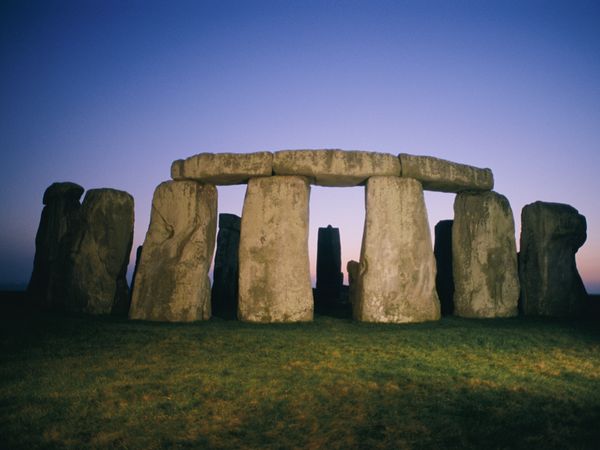

Stonehenge at dusk; ancestral gathering spot? (jphoto by Joel Sartore)

Megaithic mausoleums

The mystery of Stonehenge has attracted worldwide interest, and there are many theories about how and why it was built. The alignment with the solstice sunrise is well-known, but its use remains an enigma. Recent years have suggested though that it may have been a huge monument to the dead.

The National Geographic carries an article describing work carried out by Sheffield University’s Mike Parker Pearson, co-leader of the Stonehenge Riverside Project. ‘Latest discoveries by the project,’ writes the magazine, ‘appear to support Parker Pearson’s claim that Stonehenge was a center for ancestor worship that was linked by the River Avon and two ceremonial avenues to a matching wooden circle at nearby Durrington Walls. The two circles with their temporary and permanent structures represented, respectively, the domains of the living and the dead, according to Parker Pearson.’

“Stonehenge isn’t a monument in isolation,” he says. “It is actually one of a pair—one in stone, one in timber. The theory is that Stonehenge is a kind of spirit home to the ancestors.”

As for the massive Avebury stone circle which I recently visited, human bones found nearby point to some form of funerary purpose. These are not unlike the human bones found at similar sites. ‘Ancestor worship on a huge scale could have been one of the purposes of the monument and would not necessarily have been mutually exclusive with any male/female ritual role,’ says Wikipedia.

Our ancestors practised ancestor worship on a grand scale, it seems. Today in Kyoto the spirit of that past is still very much alive.

Avebury rocks!

Avebury rocks!

I began reading about Shinto about a year ago and as I read the first book, Understanding Shinto by C. Scott Littleton, I couldn’t help thinking that if European paganism had survived it might look very similar.

Hello Ken… It’s a good point. One of the attractions of Shinto is that many of the ancient forms have survived. I think that is what appeals to many people, and why Thomas Kasulis writes in his book on Shinto of a sense of ‘coming home’. There’s something in it, as Donald Richie said, that speaks to our innermost nature, as if a voice from our primordial past.

I enjoyed the Way Home. I’ve just discovered your site and enjoy it very much. I hope your next book is on the links between Shinto and the Neopagan revival in the West and how we, as westerners, would adapt Shinto, and vice versa. I live close, relatively close anyway, to the Tsubaki Grind Shrine in Washington State. I need to get up there and visit.

Hi again… Thanks for the input. I certainly want to write of Shinto and the Neopagan revival and am doing research to that end. But in the meantime I’ve got another project on World Heritage Sites in Japan which is taking up my time. As for the Tsubaki Grand Shrine, I’d certainly encourage a visit as it’s a place with a very special sense of atmosphere, plus the folks there are most welcoming. Look out for the Dougill bell when visiting!