Shrines for the Chinese zodiac at Hakusan Jinja, Hiraizumi

Over the past fortnight I happen to have come across the Chinese zodiac in various guises. A set of 12 small shrines (hokora) for each zodiac year at Hakusan Jinja in Hiraizumi. A full set of 12 zodiac ema (votive tablets) at Toshugu Shrine in Nikko. A set of eight protective Buddhas for the 12 zodiac years at a temple near Utsunomiya. And now back in Kyoto, seven protective kami at my local shrine of Shimogamo.

Now here’s an odd thing: why do the Buddhists have eight protectors, whereas Shimogamo Shrine has seven protective kami? Eight is a number which traditionally signifies limitlessness (as in ‘eight myriad kami’). Seven on the other hand is a magical number, much treasured in Daoism (as in the 7-5-3 festival). Could the numbers have something to do with it?

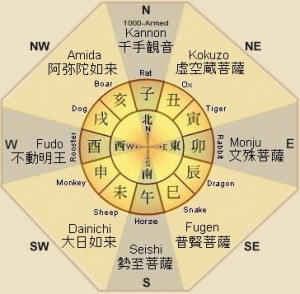

For an understanding of the Buddhist situation I turned to Mark Schumacher’s excellent onmark website. “The Zodiac’s popularity in Japan peaked during the Edo Era (1600-1868 AD), by which time each of the 12 animals were commonly associated with one of eight Buddhist patron protector deities (four guarding the four cardinal directions and four guarding the four semi-directions; the latter four are each associated with two animals, thus covering all 12 animals). At many Japanese temples even today, visitors can purchase small protective amulets or carvings of their patron Buddhist-Zodiac deity.”

Buddhas for the four directions and four sub-directions cover the 12 different zodiac years (Illustration taken from the onmark website)

The Seven Shinto kami

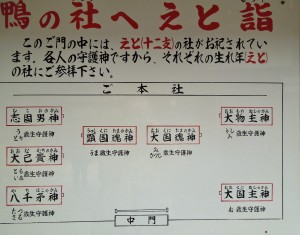

Given Japan’s syncretic tradition, one might assume that Shinto would simply have eight kami equivalents of the Buddhist deities. However, at Shimogamo that is not the case and the shrine boasts seven ‘hokora’ (small shrines) in front of the main shrine. I’ve been visiting mine (Ushidoshi) for the past fifteen years. Recently I’ve noticed that, following major renovation at Shimogamo, the diagram below has been pinned up to guide worshippers to their relevant birth sign.

The chart tells us that the seven protective kami are as follows;

1) Shikoo no kami (Rabbit and Rooster) 5) Ookunitama no kami (Snake and Sheep)

2) Oonamuchi no kami (Tiger and Dog) 6) Oomononushi no kami (Ox and Wild Boar)

3) Yachihako no kami (Dragon and Monkey) 7) Ookuninushi no kami (Rat)

4) Utsushikunitama no kami (Horse)

Layout of the seven guardian kami

Now it’s difficult to see much rhyme or reason to this. Why do the rat and horse get a kami to themselves? What joins the rabbit and rooster together? And what kind of kami are these figures anyway?

If one looks at the traditional order of the Chinese zodiac, it begins with the rat, followed by ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and wild boar (pig in the original Chinese). Applying the order to the Shimogamo shrines, as I’ve done in the pictures below shows an interesting paired sequence that runs 2 – 12; 3 – 11; 4 – 10; 5 – 9; 6 – 8. Number 1 and number 7 are singled out, perhaps because they mark the beginning of a half-cycle? Intriguing… or is this simply a red herring?

Puzzled, I made enquiries at the shrine where a miko shrine attendant told me that there were various theories, but no one knew for sure. Later a priest told me over the telephone that the shrines were thought to date back to Heian times, and that the division into seven guardians likely derived from Chinese yin-yang and the 5 elements. The seven protectors were in fact seven different names for one and the same kami: Okuninushii. Perhaps as guardian of the unseen world, he was seen as responsible for whatever spirits guide the zodiac.

Like much else in the Shinto tradition, the original rationale has been lost in the mists of time, but the custom of lives on regardless. After all, only a foreigner would ever think to question it!

The year of the rat (traditionally No. 1)

Ox and Wild boar (nos. 2 + 12)

Tiger and dog (nos. 3 + 11)

Rabbit and rooster (nos. 4 + 11)

Dragon and monkey (nos. 5 + 9)

Snake and sheep (nos. 6 + 8)

Horse (no. 7)

Leave a Reply