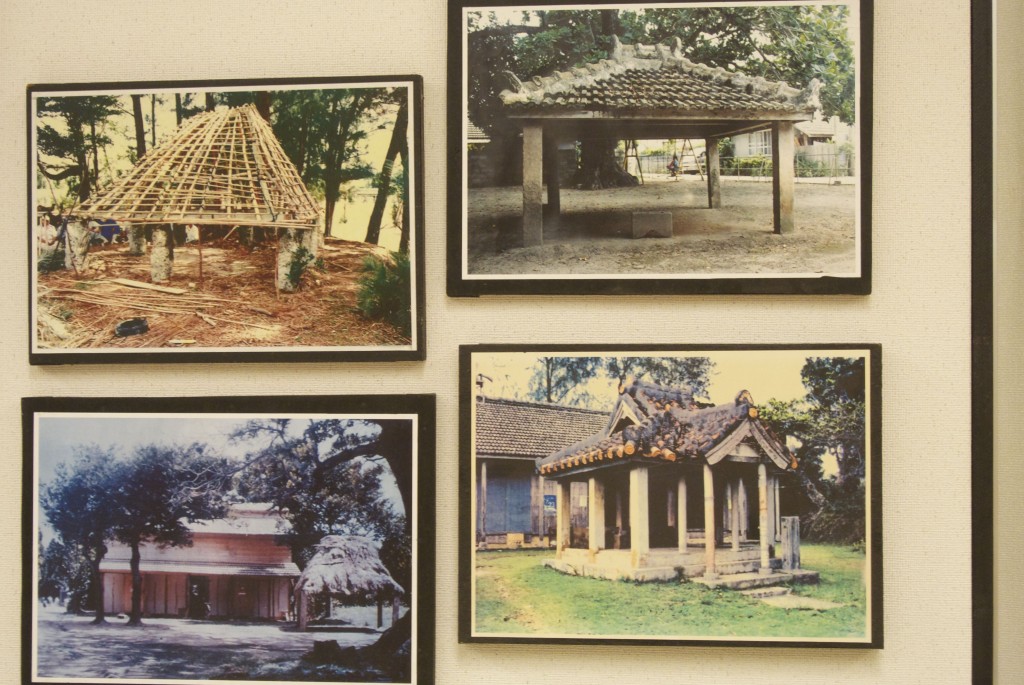

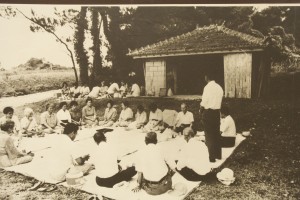

An Okinawan village shrine (photo in the Nakajin Castle Museum)

Different styles of village gathering places

At Nakijin Castle on the Okinawan main island, there is a museum with an exhibition of Ryukyu practices. It includes pictures of kamiasagi, which are gathering places for religious ceremonies. These are not to be confused with the more widely known utaki sacred sites. So what’s the difference?

The utaki were special sites where the spirits dwelled or into which they descended. As such they were off-limits to ordinary folk: only the priestesses could go there for special rites. These numinous sites were often copses or springs, far beyond the village boundaries.

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.

In response to my question about how far Ryukyu religion was still being practised, the woman running the museum told me that ordinary people still continued former practices but that the noro (priestesses) were slowly dying out. In her own village for instance, the noro was eighty years old and with no one likely to succeed her.

Once the noro had received an official stipend, but this had been stopped in Meiji times and now they had to make do as they could. For the young it was not an attractive proposition, and the daughters of noro who used to take over the family tradition often choose to move away or take up other career paths.

All dressed up at Futenma Shrine for the 7 – 5 – 3 ceremony

But even without the noro, Ryukyu practices live on. I came across an interesting example at Futenma Shrine, where 7-5-3 celebrations were in full flow. which was established as an outpost of Honshu’s sovereignty in Edo times, dedicated to the Kumano kami, and is considered one of the eight major shrines of the Ryukyus.

While most visitors carried out prayers in the conventional Shinto manner, two locals squatted before the shrine and directed their prayers in a different direction. It turned out that they were worshipping more ancient gods than those of the Jinja, for the shrine is built above an extensive cave (280 meters long), which was sacred to locals before the coming of the Satsuma invaders.

Eerie and atmospheric, the cave has a numinous quality that makes one wonder why it is kept locked up (you have to get permission from the shrine office to visit). It’s used once a year for a ceremony at which some 800 people attend, and it honours two ancient kami, Megami and Sennen (The Old Mountain Man).

Megami was a beautiful but pious woman, who wished not to be seen. However, the husband of her younger sister caught sight of her when he peeked into her house, as a result of which she rushed out and took refuge in the cave, never to be seen again. (A very Taoist tale, methinks, with overtones of Amaterasu’s Rock Cave myth.)

The legend of Sennen, the Old Mountain Man, has to do with the incarnation of a spirit who visited a poor woman, whose life was one of sacrifice and deprivation. As a test of her honesty, he gave her a wrapped item which he told her was valuable and asked her to keep it for him. Despite his disappearance, the woman did all she could to find and return the item to him, as a reward for which he presented her with gold. As a token of their gratitude, she and her husband built a shrine in the cave to the Sennen.

The cave, and the shrine above it, stand right next to the fenced gateway of the US military base at Futenma. It’s an odd juxtaposition. Here in a nutshell the history of the island is laid out, from the myths of Ryukyu times, to domination by Satsuma, to integration into Japan, and to American hegemony.

A shrine that speaks to another world turns out to have much to say about this world too.

The Futenma cave: a special space only opened on request

Haunting and atmospheric: the Futenma cave is right next to the US military base

Meanwhile, above the cave the 7-5-3 ceremonies were being carried out in true Shinto style

Leave a Reply