Is Shinto animism plus ancestor worship? Or is it ancestor worship plus animism?

There’s a big drive these days to pass Shinto off as a nature religion, but wherever you turn you’ll find the ancestral aspect can’t be ignored. Look through the newly published Shinto Shrines for instance, and the overwhelming majority of kami worshipped are ancestral in nature. In an earlier posting I wrote arguing that animism trumps ancestor worship (click here). Now I’d like to argue the exact opposite.

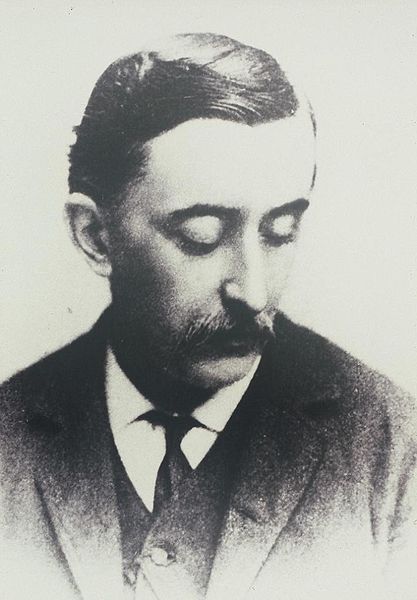

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904)

In Lafcadio Hearn’s Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation (1904), the Irishman makes a powerful case for seeing the whole of Japanese culture, not just the religion, through the lens of ancestor worship. ‘Almost everything in Japanese society derives directly or indirectly from this ancestor-cult; and that in all matters the dead, rather than the living, have been the rulers of the nation,’ he writes.

The book has some bluntly stated convictions. Early ancestor worship, based on a belief that ghosts were the spirits of the dead, is ‘the root of all religions’. It was a theory propounded by Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ as he was known. According to his thinking, ghosts came to be seen as spirits of relatives and ancestral figures that live on after death.

The ancestral spirits were ascribed superhuman powers, such as the ability to protect or punish the family household. Offerings were therefore put out for their well-being, and ‘hungry spirits’ who felt neglected by their heirs were thought to wreck havoc as a result. In other words, ghosts were turned into gods.

Hearn’s argument is that ‘the cult of the dead’ became deeply ingrained in Japanese thinking, such that it lies at the core of both Shinto and Buddhism. It found expression in three main spheres: the domestic, the communal and the national. In the domestic sphere, family ancestors (specifically the previous two generations) are honoured at a family shrine or altar. At the communal level, neighbourhoods join in worshipping their clan ancestors in a local shrine (ujigami). And at the national level, people honour the imperial ancestors.

In this way ancestral worship affects all elements of the culture. Individualism was suppressed as a result, because of the tendency to see oneself as part of a household, or as part of an ancestral line. Instead of putting oneself first, there was an emphasis on loyalty, groupism, self-sacrifice, hard work, honesty, purity and consideration of others. ‘Spirit eyes are watching every act; spirit ears are listening to every word [-] the heart must be pure, the mind must be under control..’, he writes. It was such thinking, Hearn argues, that shaped the charm, grace and selflessness of the Japanese female.

Hearn's house in Matsue, Shimane prefecture

According to Hearn, animism is a later idea than ancestor worship and was imported from China. The idea that animism preceded ancestor worship is ‘old-fashioned’, he claims. ‘The earliest Shinto literature gives no evidence of such a developed animism as that now existing,’ he goes on.

There’s much in Hearn’s book that has one nodding in agreement, despite the intervening 100 years of Westernisation. It’s a tribute to his perspicacity. He even seems at one point to be predicting the kamikaze spirit of WW2 as he writes of the fanatical desire for self-sacrifice to which the culture can lead, describing Shinto at the national level as ‘a religion of patriotism’. He offers an explanation too as to why Christianity has failed to make inroads in Japan, in that it has not accepted ancestor worship.

Even within a Westernising Japan can be discerned the unmistakable shape of ancestor worship, claims Hearn, comparing the situation to a topiary left to its own devices – though it becomes overgrown, the original shape can still be made out, fainter and less obvious perhaps but nonetheless clearly discernible.

One of my good friends, a Japanese university teacher, is a sophisticated woman with thoroughly Westernised tastes, who graduated from a Christian school and university. ‘It’s very strange,’ she said to me once. ‘I don’t believe in religion or gods or anything like that. But I pray to my father every morning, offer him food and tell him what’s on my mind. I don’t know why, but it seems natural to me.’

Full marks to Hearn – I think he hit the nail on the head. There’s good reason that his books remain in print, and after enjoying Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation so much, I can’t help looking at him as a kind of kindred spirit. An ancestral spirit, indeed, of the non-Japanese community in Japan.

View towards Hearn's house in Matsue, where he first learned about Japan's ancestor worship

I have noticed that all of Asia seems big for ancestor reverence. Feng Shui was invented to bury the dead where they’d be happiest and most helpful.

And in West Africa, in Vodou and Santeria the ancestors are major players. Ditto for Heathens. And modern neopagans have tried like me to incorporate it as it seems universal.

But what if you hated your ancestors? What if they were rapists and slavers and cruel and harmed many? What if they abused you? And you know it meant they were abused, and so it’s inter-generational, how do you deal with that?

I have tried seeking for some mythical ancestors way way back but honestly I am not thrilled about my cultures with sexism and slaves, even though those were the norm for Pagan society, and yes, the Germanic and Irish women had it better than the Roman.

I can only go to what I imagine my blood line was doing pre-pastoral, pre-agricultural, when there were no slaves (but Newgrange obviously had slavery involved), no one had private land or possessions, gatherer-hunter-fishing-gardening ways. Pagan Europeans clear cut Europe. The whole invasions of Ireland myth is people clearing fields.

Both my parents are mentally ill so I raised myself. I am feral. My grandparents harmed my parents and their parents were worse if possible as they just did the Calvinist self hate thing and judge others. Rape and beat kids. Drink. Hide it all. Go to church.

I finally ended ties with my living family due to their abuse. I don’t want my ancestors who made them as awful as they are to me, I do not want them near me.

I think once upon a time my ancestors were loving, sane people. Being recent American immigrants and it not working out at all, I think there is a common Americana PTSD, a nation of refugees, slaves, poor huddled masses, all with intergenerational PTSD and no connection to the land where their families are buried. We have no Day of Dead, no visiting graves, no sleeping on their mounds for a vision. Americans I think have the hardest time with ancestors for these reasons. Many were embarrassed for having accents or different ways, like my family. Culture goes underground. Names change. We blend in a mixing pot til it is grey brown and homogenized. Even most of the Natives here do not live where their ancestors did being forcibly moved in the genocide that still faces them. African-Americans, who do they remember? While Americans can be all pro-IRA and say they are soppy drunks and brawlers because they are Irish, the exact things used to oppress the Irish, and Ireland makes its living on selling Ireland to 1/8th Irish-Americans, where can the African-Americans go? The back to Africa movement in the 20th century was small and brief.

When your ancestors are in the land where you are, it’s much easier.I also think that if you are in a culture or family where people helped and loved you you’d want them still guiding the family.

What no one asks is what if your ancestors should have been imprisoned (mine should have) and the layers of abuse are so deep there is no one dead you feel safe with?

I cannot get a good answer. I started an ancestor shrine, over 300 names of dead peace and justice movement ancestors. Joe Hill, Dorothy Day, Eugene Debbs, Ghandi, MLK, John Lennon, Joe Strummer, Bob Marley, Arne Naess, Sandanistas, Zapatistas, Muslim feminists, gay rights leaders, landless peasant leaders, farmers organized against Monsanto, conscientious objectors to the Revolutionary War, Civil War, WW1, WW2, Vietnam. None perfect humans but people I would like to guide me, protect me, aide me, comfort me.

Buddhists, like many religions, have the restless dead. It’s weird because the newfangled American “live like a monk to get rich” don’t pray for the restless dead. It’s glossed over when it is key to metta. The US is filled with restless dead, our land is soaked in blood, but it is land no one feels they belong to. American is more of a concept than a place, very large and united by cable TV. We are all ancestorless or if we know them, usually are not thrilled with them. We may have names but nothing else. They’re back behind the Rio Grande where we will never see them again as we work to send money home and avoid arrest and withstand violence and verbal attacks.

When I am in Ireland where my Grandma lived I feel very well. Where my Mom’s Grandpa lived I feel sick.

Hello, Heather…

You raise an interesting point about the disconnect with ancestors, and I’ve never come across anything in Shinto that is relevant to it. However, shamanism has a lot to say on the subject and has developed sophisticated rituals to go along with it… but no doubt you’re familiar with all that.

In Shinto I think the attitude would be to focus on gratitude for what is handed down (the miracle of life). In my experience, it prefers to deny, ignore or accept the negativity, but not to confront it. Many of the kami for example have an evil side which causes earthquakes and other disasters, but that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t honour them…