*********************************************************************************

Imported and amalgamated kami

These deities came either with the immigrants who had worshipped them in their own land, or by way of Buddhism which brought with it Indian, Chinese, and Korean traditions (including Daoist and Confucian elements). Some of the deities are called by the generic term banshin. Such gods as Gozu Tenno of Yasaka Jinja originated outside Japan. Buddhist deities were also called banshin, but in later times the term was most often applied to deities worshipped by Korean immigrants.

In most cases deities were not simply imported, but amalgamated and mixed with native traditions to the extent that they became “original Japanese” deities.

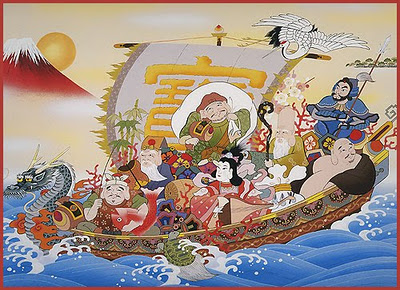

One particular grouping of imported and domestic gods came to be known as the shichifukujin (“seven lucky gods”), which are worshipped at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines alike. They are originally individual deities that were brought together as a group in the fifteenth century, probably under the influence of the Daoist tale about the “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove.” They are often depicted together, riding in a treasure boat (takarabune), and are the most visually represented kami in terms of paintings and sculpture.

As in other parts of the world, in Japan seven is an auspicious number, and a shichifukujin pilgrimage (shichifukujin meguri) is conducted around the New Year to pray for happiness and prosperity. The pilgrimage, which predates the popular first shrine visit of the year (hatsumode), is usually a short route of seven shrines or temples that can be completed easily in a few hours. The deities are so well known and loved in Japan that a more detailed description of them follows here.

The Seven Lucky Deities

Bishamonten: This is another Buddhist-absorbed Hindu god, which was originally called Vaisravana. Bishamonten is one of the “four heavenly kings” (shitenno) that guard the four directions. He is a fierce warrior god who expels demons and protects worshippers of the Lotus Sutra. He is often depicted holding a spear in one hand and a pagoda in the other. The pagoda represents the treasure house that he protects and the treasures that he distributes. Considered a god of fortune, the deity is also known as Tamonten.

Daikokuten and Ebisu, a happy pair of good fortune deities

Daikokuten: The deity started as the Hindu god Mahakala, depicted as a black, multi-armed deity. In China he was adopted into Buddhism as a deity of the kitchen. The Chinese characters used for his name mean “big black.” In Japan he also became associated with Okuninushi no mikoto, in which case he is called Daikoku (“great land”) sama. A god of wealth and the bountiful harvest, he is usually depicted sitting or standing on bales of rice while holding the mallet of plenty in one hand and a sack of treasure slung over his back with the other. He is also a god of fertility and often depicted as a pair with Ebisu.

Ebisu: The only original Japanese god in the grouping, Ebisu is a deity of fishermen and good fortune. His origin is ambiguous, but he was always found in fishing communities and is strongly related to a bountiful catch. He is depicted holding a fishing pole and a sea bream, which is called tai in Japanese. The fish is associated with good fortune because the expression omedetai means auspicious or joyous. Ebisu is the happiest of gods and reflective of the simple joys of the common people. He is sometimes considered the son of Daikoku.

Fukurokuju: A Chinese sage of good fortune, probably originating in Daoist tales. Associated with wealth and longevity, he is always depicted with an elongated, phallic-looking forehead, long beard, a staff and a scroll of the Lotus Sutra. He is not amalgamated with Buddhist or Shinto deities. As a god of wisdom, good fortune, virility, and longevity, he expresses typical concerns of the Daoists.

Jurojin: Another Daoist sage, Jurojin is most likely the same god originally as Fukurokuju. Though he is not usually depicted with an elongated forehead, all of the other physical aspects and associated myths are identical. He is a god of longevity and usually depicted with animals that represent long life such as a white stag. He carries a staff and a scroll of knowledge.

Hotei: Based on a popular tenth-century Chinese sage named Pu-tai (or Budai), he is identified with the Buddha of the future, Maitreya. As a god of happiness, he is portrayed as a “jolly fat man” with a big belly sticking out of his open robe. He has a bald head and huge earlobes—signs of good luck and happiness. He carries a huge bag endlessly full of gifts together with a “wish-fulfilling fan.”

Fukurokuju, Jurojin and Benzaiten

Hotei in all his pot-bellied splendour

Leave a Reply