The extract below is taken from “Hawaii’s Domestication of Shinto’ by Dr. James Whitehurst, who was professor of religion at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington. The article first appeared in the Christian Century November 21, 1984, p. 1100. The full article can be accessed here.

*******************************************************************************

Izumo Taisha in downtown Honolulu

I discovered that Shinto had come to Hawaii with Japanese workers looking for jobs on the sugar plantations a little more than a century ago. When they found they liked Hawaii and decided to stay, the workers sent word home for brides. Parents arranged marriages, and soon boatloads of “picture brides,” as they were called, landed in Honolulu. Although marriages had been meticulously planned, the missionary-educated Hawaiians had qualms about their legality. To satisfy the public outcry, hasty weddings were arranged. At the Izumo Taisha shrine in downtown Honolulu, there were as many as 100 weddings a day. From these unions issued a population explosion that soon flooded the islands.

The immigrants brought with them their godshelves (kamidana) and the numerous festivals (matsuri), primarily associated with the agricultural cycle. As they became prosperous and moved to the cities, they constructed Shinto shrines. Their celebrations, especially the New Year’s festival, became a part of the Hawaiian landscape.

America prides itself on its religious pluralism, its hospitality to all races and religions. But how did a religion which was so much a part of the distinctive Japanese way of life manage to survive on U.S. soil?

My search for an answer took me first to an investigation of the postwar status of Shinto in Japan. In an interview with Professor Naofusa Hirai at the Kokugakuin University (a Shinto institution) in Tokyo, I learned that Shinto is a religion of nature; its deities (kami) are personifications of natural forces such as rivers, seas, mountains, fire and wind — powers that create a sense of awe and wonder in the human spirit.

Daijingu Shrine in Honolulu

Professor Hirai regrets the way Shinto became a tool of the state, a part of the war cult. “Shinto is eager,” he said. “to shake off these nationalistic accretions and move strongly in the direction of internationalism.’’ He, with other Shinto leaders, would interpret the phrase Hakko Ichiu (the world under one roof) as pointing to the goal of democratic world government. Far from being supernationalistic, Shinto priests today are often active in peace movements.

In returning to Hawaii, I wanted to see how this new interpretation was working in the States. I interviewed Bishop Kazoc Kawasaki, head priest of the Daijingu Shrine on Pali Highway in Honolulu. Kawasaki was himself a victim of wartime prejudice and spent most of the war years in the relocation center at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. From him I learned how easy it is for Shinto to adapt to new situations, since one of its major teachings is just that: to blend with the social and cosmic environment.

Kawasaki, a skillful communicator, employs numerous Western teaching methods such as flip charts and object lessons to get his point across. Although Shinto has generally been viewed as polytheistic, Kawasaki’s flip charts show a decidedly monotheistic emphasis, which undoubtedly communicates better to a Western-educated audience. One Creator God, Hitori Gami. is shown as the source of all lesser kami manifestations.

Kawasaki held up a fun-house mirror at the center of the sanctuary near the large, round mirror that symbolizes Amaterasu, the sun goddess. “We should be perfect mirrors, clean and without blemish,” he said, “and not distort things as this fun-house mirror does.’’ Later he displayed a group of billiard balls in a triangular rack and showed how each ball moves in relation to the others. Comparing them with a display of square blocks, he said. “These cubes are too individualistic: they can’t move well with their surroundings.” A beautiful illustration of accommodation!

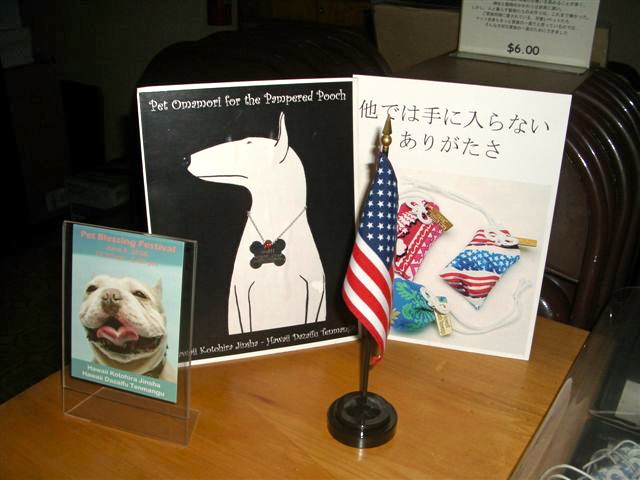

Shinto adaption to the American love of pets: advertisement for pet omamori

In the shrines of Hawaii, I found many examples of survival through adaption. Shinto has not yet succumbed to the Sunday-morning service, as has Buddhism; it celebrates in the evenings on specified days of each month, such as the 10th, 15th and 29th. But a sermon has been added to some services; wooden chairs often replace tatami mats with rounded pillows on the floor: tape-recorded music sometimes replaces the sound of drums, wooden blocks and bamboo flutes. Instead of a bamboo dipper at a basin of flowing water for purification at the entrance to a shrine area, one finds a water faucet, paper cups and a paper-towel dispenser! So far, there is no sign of Bingo, but shrines do regularly have their raffles. Stacks of rice flower, sake and fruit are often placed at the altar; after the gods have consumed the “essence,’’ the food is given away at the end of the services as door prizes.

Through such adaptions, Shinto has made itself at home in its American setting. But Americanization is usually a two-way street. Is there anything to be learned from a religion as alien as Shinto?

Through the years, I have come to respect and appreciate it in ways that would seem impossible for one who grew up during World War II. For one thing, Shinto offers a needed corrective to our domineering attitude toward nature; it maintains a fine-tuned sensitivity to the “ground of Being,” an intuitive awareness of the mystery which created and sustains us. Shinto shrines, with their unpainted surfaces and natural beauty, conjure up a feeling of sacred space as well as provide a place for quiet withdrawal.

Passing under a torii arch and washing one’s hands creates an atmosphere of readiness and receptivity. And when one arrives at the portal of the shrine, the simple clapping of the hands and bowing deeply helps one to restore a cosmic balance. Note that it is not an attuning of oneself to nature, as though nature is something outside the self; the Japanese have no word for “nature’’ in that sense. Yet it would be overly romanticizing to say that everything in modern Japan shows a perfect blending of humans and the environment; that is more likely a private achievement, expressed more in one’s enclosed garden than in the public arena — witness the beer bottles littering the pilgrim’s path up Mt. Fuji!

Car purification in Hilo: Shinto has little trouble adapting to modernity or the American way of life

Is nature mysticism impossible in a secular age then? Alfred Bloom of the University of Hawaii’s religion department thinks not. He insists that Shintoists. for all their love of nature, are still firmly grounded in the mundane world of business and economics. A Shinto priest sees nothing incongruous about waving his harai-gushi (purification wand with paper streamers) over the nose cone of a Boeing 747 and blessing it for secular use. Even in the machine he senses something that is more than just machine, since the divine is at the heart of all matter, even the technological products humans create. Perhaps there is something here that Westerners can appropriate.

If there is something to be gained from Shinto, there is also a pitfall to beware of: the peril that comes from too closely associating religion and culture. Shinto now regrets its close wartime associations with an imperialistic state, when it was used as a tool by the warlords.

Traditional Hawaiian sacred site and palace; could that be a torii?!

Hakko ichiu – One world! The sun rises on all alike...

Dear John,

First let me say that I follow your blogs daily. So I found it of interest that you posted excerpts from an article that is thirty years old. Will you be writing an updated article about Shinto in Hawaii?

Hello Hana, thanks for your message. I posted the article because it gives a lot of useful background information about Hawaii… I visited there myself about seven years ago. I’ll see if I can put together a piece about it.

Even if this article is a bit old, I am glad you posted it– there is very little about this shrine available online.

I think it to be a shame that you see the only two options as extreme nationalism or Orwellian world government. Shinto is concerned with immediate surroundings, and not the affairs of other people half way around the world. The only way that things can best be governed is by local government, made by people who actually know the area. Some bureaucrats in New York City should keep their hands out of a local community’s business.

Thanks for the input, Michael. I think we basically agree. I don’t advocate Orwellian world government at all, but universalism in the sense the local is global. As an ecologist, I believe in grass-roots community power. However, it’s important to realise that these are not special in themselves but part of a world community. Think global, act local remains the guiding slogan…

Aloha from Hawaii.

I frequent three of the four shrines here on Oahu – Hawaii Daijingu, Ishizuchi, and Kotohira and if you have any questions I will do my best to answer them or find out the answers for you.

Dajingu Temple of Hawaii and Hawaii Kotohira Jinsha both have websites which provide limited information but it’s a place to start. Unfortunately Ishizuchi and Izumo do not have active websites.

Aloha and thank you for the comment… Since you frequent three different shrines, you’re in a unique position to give your impression of how Shinto is faring in Hawaii these days. Do you think it’s in decline, or is it gathering new interest? When I visited Ishizuchi, for instance, I found nearly all those attending to be elderly. Also is there any spread to non-Japanese, and if so in what form?