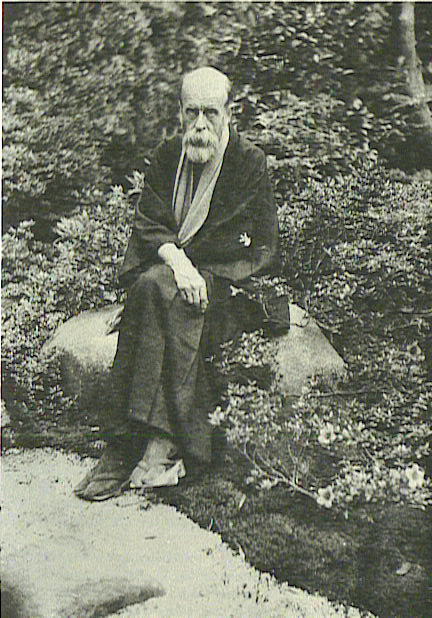

The cricket-loving, scarf-wearing Shinto expert Richard Ponsonby-Fane (1878-1937)

An aristocrat with a penchant for cricket who went native, wore Japanese kimono with a scarf, and became the twentieth century’s foremost expert on Shinto. Richard Ponsonby-Fane (1878-1937) was the archetypal English eccentric, with a hatred of modernity that extended as far as trains and electric lights. He also clung fervidly to the notion of the Divine Right of Kings, a doctrine that had gone out of fashion in the seventeenth century after Charles I lost his head.

Prewar Shinto studies involved remarkable men. W.G. Aston, B.H. Chamberlain, Lafcadio Hearn, Percival Lowell, Jean Herbert. Some explored deep into linguistic and cultural mysteries at a time when there were no guides of any sort. Their dedication is astonishing, and more should be known about them.

Of all the experts, none went as far as Richard Ponsonby-Fane in glorifying the religion. This great British scholar, born to a sizable family estate deep in rural England, forsook his family birthright for far-off lands, eventually settling in Kyoto where he delved into Shinto history and shrine lore to become such an authority that his books are still used today for research and Wikipedia entries.

The list of Ponsonby-Fane publications is remarkable, and they were collected after his death and published in six volumes by the Ponsonby-Fane Memorial Society. They are prized items. He wrote in Japanese too, and he achieved widespread respect among shrine figures. When I visited Ise once, a priest there on hearing I was from Kyoto asked if I knew of Ponsonby-Fane.

So who was this extraordinary person? Well, it turns out that he escaped the confines of British upper-class society by joining the colonial administration first in South Africa and then Hong Kong, where he became interested in Japan and started learning Japanese. Like many an expatriate, his discomfort in his native environment may have had to do with his sexuality. A confirmed bachelor, he distrusted women and in Japan lived for sixteen years with ‘a secretary’ called Sato Yoshijiro, much as Somerset Maugham in his French abode.

After he settled in Japan in 1919, Ponsonby Fane thought he had found refuge from a modernising rationalistic West. He also hated Western democracy, which he despised as government by an ‘ignorant and self-seeking mob’. Like many a reactionary, he was drawn to Shinto by its idealisation of a leader invested with divine authority. Devotion, loyalty and unswerving self-sacrifice are the virtues Ponsonby-Fane treasured in a faith he clearly found sympathetic (though he remained a high church Christian).

Like Hearn, Ponsonby-Fane sees the essence of Shinto as lying in the patriotic spirit it fostered through the person of the emperor. ‘What this country really owes to Shinto is patriotism,’ he writes, ‘for no real Shintoist can fail to be patriotic when his sovereign is also his deity… the world over the Japanese are regarded as the very incarnation of patriotism.’ Ponsonby-Fane was writing in the run-up to WW2; Hearn had written in similar vein with even greater prescience some thirty years earlier.

Ponsonby-Fane was to develop close ties with Japan’s imperial family. In 1921 he acted as interpreter to the Crown Prince (future Emperor Hirohito). He was the only foreigner invited to Hirohito’s coronation at Kyoto’s Gosho palace, and being a tall figure who stood out among the relatively short Japanese he astonished the crowd by getting down on his hands and knees in respect before anyone else. In 1930 he sailed on the same ship to Europe with Prince Takamtasu, Hirohito’s younger brother, and was invited to attend all the prince’s receptions in England. And the scarf which he insisted on wearing everywhere with his kimono was apparently knit for him by Empress Teimei, widow of the Taisho emperor.

Ponsonby-Fane succeeded to his family estate, a large property in Somerset, and could have gone home any time he wanted to live the pleasant life of an English country gentleman, but he chose to remain in Japan and dedicate himself to Shinto studies. His final eight years were spent at the house he built for himself near Kyoto’s Kamigamo Shrine. It incorporated shrine elements into its design, finished off with his family crest on the eaves. He was friends with local priests, and at the Kyoto Middle School where he taught he was known as Dr Ofuda (ofuda hakase) because of his collection of shrine talisman. He died shortly before his sixtieth birthday, spared the dilemma in World War Two of having to choose between the stately home where his ashes are buried and the country he so eagerly embraced.

Thank you for your tribute to this forgotten genius.

Now I know why you ran away at the Hailstone ‘Cities of Green Leaves’ event in June 2011 somewhere near Kamigamo. It was Ofuda-hakase’s house you were shown that day, right? Fascinating account, although slightly sad that he became so estranged from his own country. It was not as easy then as it is today to flit between the two worlds.

I was looking for something about Ponsonby Richard (Fane) and ran into your website. This was because my grandfather’s elder brother used to be an assistant for this gentlman’s research on Japan. It seems my grandfather used to drive around to shrines and temples for Mr Ponsonby (his research) and also attended to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Yappu Island etc while Kyoto was in the severe cold season of winter.

Hello Yumi… how very fascinating!! I read about the man who assisted and drove for Ponsonby Fane. Did he marry in later life? I wonder if you heard anything about what happened to him from your grandfather….

Very interesting. I just purchased an old book, “A Study of Shinto,” by Genchi Kato, signed by the author and apparently gifted to “Ponsonby-Fane” when it was published in 1926. I wonder if I’ve come upon a book from this man’s book collection?

“But it is worthy of note that the Nihonshôki specially records that the Emperor “in person” carried out the priestly functions, a point that Père Martin, the latest interpreter of Shinto to foreigners, in his book Le Shintoïsme, seems to overlook; for when discussing whether the Sovereign of Japan was also the High Priest, he says, “au Japon, rien de tel.” It would seem to me, and evidently did also to the late Mr Aston, that in the early days the Sovereign was beyond question regarded as Priest Emperor, though in an ordinary way he entrusted the affairs of worship to the Nakatomi and Inbe [clans].”

— Studies in Shinto & Shrines, first chapter (the Shinto Theogony), by R. A. B. Ponsonby-Fane

Clearly, Ponsonby-Fane was not as confused by the notions of Regnum, Imperium, Divus & Deus, and Pontifex & Pontifex Maximus, as are modern & postmodern folks inducted either by the Siècle des Lumières or by Cultural Marxism, if not both of them, as is proven by the ridiculous interpretation they give of the Ningen Sengen (and also what they understand by “Humanism”). Maybe that’s because we are not affected by such preposterous ideas that I and Ponsonby-Fane “cling fervidly to the notion of Divine Right of Kings” even though it is “out of fashion”, and as been replaced by Democracy, which is to say a “Telluric-Chtonnian daemonic right of the Mob” form of Greek Athenian Paganism.