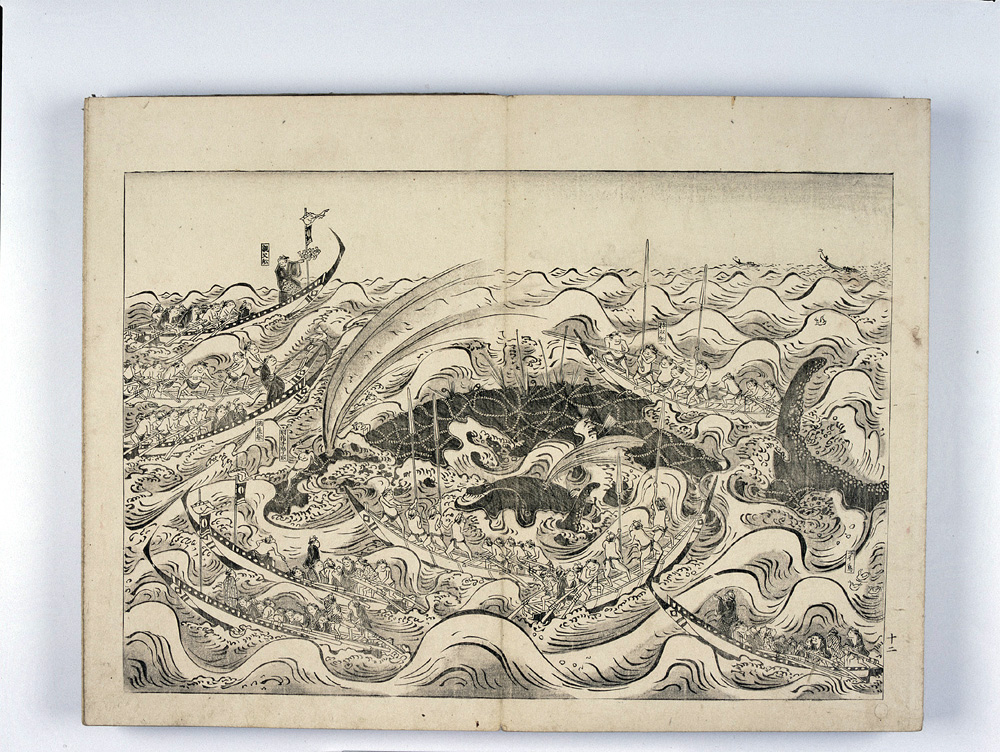

(courtesy of Nat. Geographic)

Green Shinto is vehemently opposed to whaling on the grounds of cruelty. Moreover, there’s a nasty ‘stink’ about every aspect of the Japanese whaling industry. The downright deceit. The hidden political subsidies. The ties to the yakuza. The nationalist subterfuge. The slow deaths. The slaughter of mother whales. The illegal imports from Norway. The feeding of contaminated meat to schoolchildren.

It’s often said that in keeping with shamanic practices, Shinto honours the soul of animals sacrificed for human need. Some even claim that this excuses the killing, for it is done with reverence unlike ‘materialistic’ cultures which consume living beings as if they were objects. It’s not an argument we find persuasive. If a murderer performs a ritual of placation for the soul of his victim, should he be forgiven for whatever brutality he carries out?

In a fascinating article in the Japan Times, the topic is taken up by Shaun O’Dwyer, an associate professor at Meiji University. The conclusion he comes to is instructive: “While most Japanese today rarely eat whale meat, some defend pelagic whaling out of a belief that Japanese eating habits should not be dictated to by foreign activists. But if such advocates could commune with the poets and whalers among their own ancestors, they would feel their dismay at the impious waste of whales’ lives in the name of “research whaling.”

In the thoughtful article below, you can read how he reaches such a conclusion.

******************************************************************

A Japanese poet’s whale elegy

In November 2011, while cleaning up tsunami debris as a volunteer in Miyagi Prefecture, I visited the tsunami-damaged port of Ayukawa. On that bleak day it was a desolate sight. Piles of rubble littered the shorefront, interspersed with gutted buildings and a collection of whale skulls — but little else to tell that this had been a prosperous whaling port five decades ago.

As I looked on, I remembered a verse from Misuzu Kaneko’s poem “The Whale Hunt”: “The whales no longer come here/And this coast has fallen on hard times”.

A native of the whaling town of Senzaki in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Kaneko knew the old whaling culture well. It features sometimes in the natural, spiritual world depicted in her poetry; a world she represented with the honesty and wonder of a child’s eye view.

Kaneko’s life, tragically cut short in 1930 by suicide, has been dramatized for television and film. Rather than dwell on her biography though, I will introduce another of her poems, “Whale’s Memorial Service”, which can give insight for whaling advocates and critics alike into Japan’s old coastal whaling cultures:

A whale’s memorial service comes

At the end of Spring,

In the season when they catch flying fish.

While the bell tolls at the beach-side temple

Its sound floating across the water’s surface

And while the town fishermen hasten

In their haori coats to the temple

A solitary whale calf cries offshore

To the striking of that temple bell;

He cries “Koishi, Koishi!”

For his dead mother and father.

But how far does the sound of the bell

Carry out to sea, I wonder?

I thought this was an anti-whaling poem when I first read it three years ago. But I was less sure after reading “The Whale Hunt”, which is a masculine, nostalgic celebration of the open boat whaling that began in the 17th century in towns like Senzaki.

We need to pause over the more enigmatic aspects of this poem to get at its insights. What was the purpose of whale memorial services?

Whaling shrine at Arikawa Shinkamigoto (wikicommons)

Kaneko’s old-time whalers led superstitious lives, just as old time fishermen the world over have. Their folk-Shinto world was filled with spirits inhabiting places and things, both living and inanimate. Correct rituals had to be observed to appease these spirits, for the things received from nature, and nothing was to be wasted.

Buddhism overlaid this animistic piety with rites for memorializing whales, such as the ceremony referred to in Kaneko’s poem. Buddhist rites for animals used as food and for scientific experimentation are in fact common in Japan, and many Japanese hold Buddhist ceremonies for their departed pets. But rites dedicated to whales were sometimes special.

In the old Japanese whaling towns Buddhist temples house stone memorial monuments (kuyo-to) to whales and practiced (or still practice) annual whale memorial ceremonies, sometimes with an elaboration usually reserved for departed human souls. The wearing of formal haori coats indicates the seriousness with which they were taken.

At the Kogan-ji Temple in Kaneko’s hometown, whale fetuses discovered inside slaughtered whales were buried in a special tomb. The temple also holds a remarkable nonhuman funerary register (kakocho) recording the spiritual names (kaimyo) given to whales caught by whaling crews in the 19th century.

Anthropologists explain that these rites accorded such respect to whales’ spirits to express gratitude for what was taken from them and to console them.

In the uncertain, dangerous world the whalers inhabited, declining catches and disasters were also seen as the revenge taken by angry whale spirits, so performing memorial services could help guarantee good future hunting seasons.

Modern coastal and pelagic whalers still observe some of these rituals, seemingly reinforcing arguments that modern and pre-modern whaling share in the continuity of a tradition.

Yet Kaneko’s poem invites us to delve deeper into the spiritual worlds of the old whaling towns. For the imagined grief of the orphaned whale calf momentarily distracts the child narrator of the poem; it is as if, for a short while, ritual alone will not compensate for the calf’s loss.

And here I think Kaneko reached beyond cultural traditions to a universal sense of conscience. In the minds of very young children, there is not yet a firming up of the boundaries of what philosopher Roger Scruton has called the “moral community,” through which societies distinguish those (mostly human) beings whose lives must be cherished, respected and protected from those beings which may be treated more simply as resources.

In a number of her poems, Kaneko faithfully captured the disquiet of sensitive children as they become aware that their sustenance requires the taking of animals’ lives. This is not to say that such children, in Japan let alone anywhere else, will become vegetarians.

What “Whale’s Memorial Service” hints at is the role that memorial services played in allaying such disquiet in people whose livelihoods depended on the taking of whales’ lives.

Buddhism in particular gives room for flexibility over how the moral community’s boundaries are to be drawn, and for spiritual disquiet over how they are drawn.

So for people like the child narrator of Kaneko’s poem who observed that, rather like humans, whales raise and keep their young close to them, that they can be courageous and strong, and that they suffer and bleed copiously when harmed — the Buddhist rites, I believe, were also meant to ease their guilty consciences if they arose.

What on earth could industrial factory ships in the Antartic have to do with traditional whaling? (courtesy Taiji action group)

This is also the opinion of anthropologist Kato Kumi. The priest at the Kannon-ji Temple in Ayukawa agreed when I spoke to him recently, though he did not specifically address the narrator’s standpoint in Kaneko’s poem.

He stated that “in addition to consoling whales’ spirits, the meaning of memorial ceremonies includes one’s own guilt and apology for killing them”.

Assuming that Kaneko’s poems take us into the spiritual hearts of the old coastal whaling traditions, we can draw some conclusions from the insights they yield.

First, modern environmentalists are not alone in treating whales as “charismatic megafauna.” Kaneko and her old time whalers did so too, in their own way.

Second, there is a spiritual depth in the old coastal whaling traditions that whaling opponents should acknowledge. Understanding it, critics will no longer stare in bafflement at monuments commemorating the souls of whales, as some activists visiting Taiji do in the documentary “The Cove.”

Third, however, it is obvious that today’s pelagic whaling industry, with its corrupt influence peddling and its mountains of warehoused, surplus whale meat, has very little in common with the traditional whaling practices Kaneko remembered. Coastal whaling communities may better claim such a connection, but their way of life is dying.

While most Japanese today rarely eat whale meat, some defend pelagic whaling out of a belief that Japanese eating habits should not be dictated to by foreign activists. But if such advocates could commune with the poets and whalers among their own ancestors, they would feel their dismay at the impious waste of whales’ lives in the name of “research whaling.”

A creature of beauty - but not when butchered and diced into pieces

(photo courtesy of Society for the Advancement of Animal Welfare)

********************************************

The Animal Welfare Institute works to reduce the pain inflicted on animals by humans. See here or here.

But whaling is in the Kojiki, and dolphin hunts are attested at the earliest Japanese Paleolithic sites. I am always confused, when it is argued that religious principles should be given up, why people don’t simply abandon religion altogether.

Thank you for the comment, Avery, though I’m not sure I understand your points. The Kojiki is not a Bible written by God, it’s a collection of myths and stories compiled by humans to bolster the authority of the Yamato king. I can’t imagine there’s any sane purpose in Shinto circles who would seriously advocate carrying out the practices contained in it. Would you be in favour of incest, say, because it’s mentioned in the Kojiki?

As for dolphin hunts, would you seriously argue in favour of slavery and human sacrifice being practised today because they were carried out in Paleolithic times?

Times change, religions change, and traditions change. If humans didn’t change their mind over time, it would suggest they don’t have one.

I am pleased to see Green Shinto take a stand on this horrific practice and the industry on the whole.