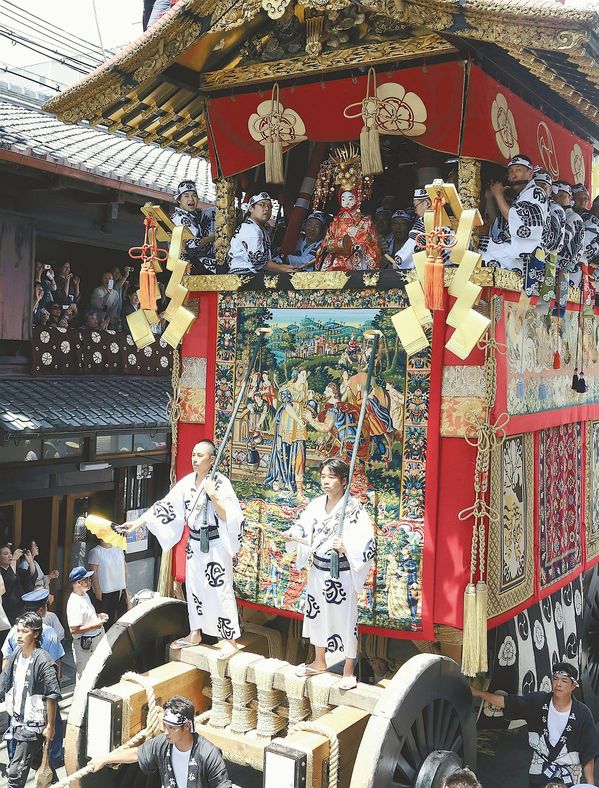

A tapestry on the front of the Kanko-boko float at the Gion Festival in Kyoto is thought to depict scenes from Genesis in the Old Testament.

In Kyoto, the Gion Festival season has opened and interest is being directed to different aspects of this ancient and most fascinating festival. One little-known point is how much Western input there is, and an article from The Japan News details how this came about.

**********************************************************************************

Western influence on Gion Festival / Popular Kyoto event has crosscultural element

July 2, 2013 Yuji Washio / Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer

Kon kon chiki chin, kon chiki chin–When the quaint sounds of little gongs begin to be heard in central Kyoto, it’s time for the Gion Festival, one of the most popular summer events in Japan.

Amid the festive atmosphere, the festival’s climax on July 17 is marked by 32 gorgeously decorated floats parading through central Kyoto. In some cases, the floats’ elaborate ornamentation includes apparently Western tapestries hanging from their sides.

Model of one of the floats on display in the days before the parade

Kyoto is a center of the nation’s weaving industry. Artisans in the Nishijin district have manufactured many tapestries for the festival.

So, why are there Western tapestries at the festival?

The festival started as a ceremony at Yasaka Shrine in 869, when Kyoto was the capital of Japan. As plagues and natural disasters were prevalent in the country that year, 66 pikes symbolizing the 66 provinces of Japan at that time were put on display to wish for peace. These pikes later became larger and more decorated until they evolved into the floats seen today.

The floats are called moving museums, as they are painstakingly made craftwork pieces. Due to their high profile, they are often regarded as the festival’s centerpiece, but they are actually meant to herald the festival’s sacred palanquin, which travels around the area where the shrine’s worshippers reside.

The 32 floats are called either yama, which means mountain, or hoko (or boko), which means pike. Of them, five use Western woven tapestries: Kanko-boko, Niwatori-hoko, Hakurakuten-yama, Koi-yama and Araretenjin-yama, that were brought to Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867).

The Kanko-boko’s tapestry, 273 centimeters by 220 centimeters, bears two different scenes on its upper and lower parts, one depicting a man receiving a large jug from a woman and the other depicting a man giving a bracelet to a woman. It is said that the scenes depict a story of the search for a wife for Isaac in the Old Testament.

Lanterns on one of the Gion floats in the evenings before the parade

According to old documents, the tapestry was donated by a local wealthy merchant in 1718, at a time when Christianity was outlawed. Yet an artwork depicting a Bible story traveled around the town–how was it possible?

“The jug is so big that it looked like a sake container. So people of the time probably thought the patterns were very suitable for the festival,” said Masutaro Matsumiya, vice director of the organization maintaining the float.

The tapestries for the four other floats are themed on the Trojan War.

Local pride

Shigeharu Sugita, director of the organization maintaining Koi-yama, said that the use of these tapestries signified the pride and power of machishu, or local citizens, mainly wealthy businesspeople who were community leaders.

“As towns holding floats were getting more and more wealthy and began competing with each other, they collected novel items [to add to their floats],” Sugita said.

Susumu Shirai, an adviser to Tatsumura Textile Co. in Nakagyo Ward, which made reproductions of tapestries of the Kanko-boko and Niwatori-hoko, said: “The originals are very elaborately made. The weavers used silk threads to give glossy texture to the patterns of clothing worn by people in the tapestry. They are expensive masterworks. I felt they represented local people’s enthusiasm for the festival.”

It is also said that the tapestries depicting the Trojan War were a gift from the pope to Hasekura Tsunenaga, who was dispatched as an envoy to Spain and Rome about 400 years ago by Date Masamune, lord of the Sendai domain.

Meanwhile, the tapestry used on the Kanko-boko was reportedly one of the gifts from the Dutch Empire to Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651), the third shogun of the Edo government, requesting the start of diplomatic relations. The piece is said to be the one recorded in a list of gifts as a “Dutch-made carpet.”

Although there is no definite evidence to support these stories, these tapestries are regarded as highly valuable.

The festival has been interrupted many times by wars, including the Onin civil war from 1467 to 1477. It was also affected by a fire in the Kinmon no Hen civil war in 1864. Only two floats, Hashibenkei-yama and Ennogyoja-yama, paraded at the following year’s festival. Nevertheless, some more floats joined the festival the next year and the number increased over the years that followed.

In 1988, with the rejoining of the Shijo-kasahoko, the current festival with 32 floats was established. The Ofune-hoko, which was destroyed in the 1864 civil war, is scheduled to rejoin the festival parade in 2014.

One of the floats with a tapestry displayed on the side below the musicians seated above, playing the characteristic Gion bayashi music

Crowds mill around the lit-up floats each year on 'yoyoyama' (July 15) and 'yoyama' (July 16) - a good time to visit Kyoto.

Very interesting! Coincidentally, I just finished reading a new fantasy novel set in present day Japan, “Eight Million Gods” by Wen Spencer, and part of the action takes place at Gion Matsuri…

Fantasy novel called ‘Eight million Gods’ and taking place at Gion Matsuri… how fascinating. Intrigued, I had to look up Wen Spencer and found this description on her website. Not my cup of tea, but please let us know what you think of it, Eric…

“Nikki is a young woman suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and a powerful mother who thinks she’s dangerously insane. To escape being involuntarily committed to a mental hospital, Nikki flees to Japan. There she’s using her compulsion to write horror novels to good use. With the money she makes writing, she can stay hidden. Her fragile peace is disrupted when she’s arrested for murder. A man has been killed with a kitchen blender, copying a character’s murder that she had posted online.

Unable to trust authorities, Nikki races to find out if she has a deadly stalker. She starts to question her sanity as her investigation expands to include Japanese monsters, gods and goddesses.”