An article in the Bangkok Post by Phil Cunningham shows the dilemma that Shinto faces, as well as Japan as a whole, by fcussing on two influential figures – finance minister Taro Aso and celebrated anime maker, Hayao Miyazaki.

Taro is a former prime minister and leading nationalist, who recently suggested Japan should follow Hitler’s lead in revising its constitution. Needless to say, he’s an ardent advocate of ministerial visits to Yasukuni and the reinstitution of the trappings of State Shinto. Miyazaki on the other hand has based several of his films on Shinto themes, in particular nature spirits and folk beliefs. (For an overview of Shinto in his films, click here. For an academic article on Shinto in Spirited Away, click here.)

The two men thus provide very different perspectives on Shinto. One seeks to reinvent an inglorious past. The other offers ecological guidance for a polluted world. In their clash of worldviews lies the battle for the soul of Japan.

The nationalist Finance Minister, Taro Aso

**********************************************************

Published: 3 Aug 2013

Unresolved issues of history continue to haunt and distort the present, all the more so when hidden from view. Historical controversies need a good airing from time to time, not so much to salvage the the past as to save the future from repetition of past mistakes.

Japan’s militarists pose a case in point. There’s no shortage of foreign media noise when ludicrous denials are made about issues such as the Nanjing massacre and comfort women, or when war criminals are glorified at the Yasukuni Shrine, but more attention needs to be directed to Japan’s ongoing argument with itself.

The latest domestic flare-up is between Japanese defenders and detractors of the Peace Constitution, known as such for its war-renouncing clause. The 1947 constitution was conceived under US guidance as an antidote to militarism, and it remains in force today, a remarkable testament to both its peaceful vision and practical durability.

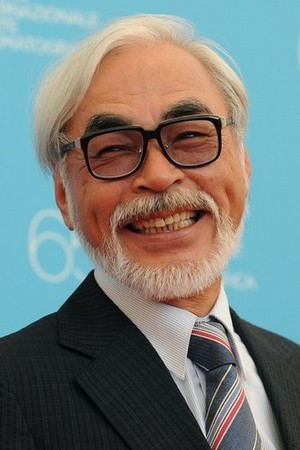

On the one hand you have the gentle and reclusive Hayao Miyazaki, anime auteur extraordinaire and Japan’s answer to Walt Disney, who broke with his characteristic reticence to state: “Taking advantage of low voter turnout and changing the constitution without giving it serious though is unacceptable. I am against it.”

On the other hand you have Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso, tough-talking political blueblood so impatient to revise the Peace Constitution that he carelessly invoked the Nazi perfidy of changing the Weimar Constitution before people realised what was going on, saying: “Why don’t we learn from that method?”

The two latest salvos cut to the quick in the battle for the hearts and minds of Japan in this moment of national disquiet. It’s an argument between those whose find strength in peace versus those who find strength in war, a battle between the better and lesser angels of Japan’s sometimes militaristic nature.

Although both men were mere toddlers during the Pacific War, seven decades later it continues to haunt them. Tokyo-born Miyazaki was left with a life-long fascination of airplanes – tales of daring aviators… The provincial Mr Aso, who was a crack shot with the rifle as a youth, a shooter in the 1976 Olympics and something of a Yasukuni crackpot in old age, had a career trajectory shaped by the guiding hands of an elite family with links to both war criminals and postwar elite. The family firm Aso Cement, which he helmed in the 1970s, had a history of exploiting Allied POWs for unpaid slave labour during the war.

On a lighter note, Mr Aso has been dubbed Japan’s number one manga fan, based on frequent media sightings of him reading boy’s comics, an association further bolstered by his claim of reading 10 or 20 manga a week, including Golgo 13 and other teen fantasies about assassins and warriors.

Around the same time, Miyazaki penned the apocalyptic manga series, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which launched his lifework of creating morally nuanced animated films laced with themes of flight and escape.

Miyazaki is an ardent defender of the Peace Constitution, but he is no more willing than his political nemesis Mr Aso to consign to the dustbin of history the entire war generation of Japanese men and women, many of whom were hapless ordinary folk doing their best to survive. It is precisely this kind of nuance that animates Miyazaki’s best work; his characters are idiosyncratic, individualistic, stubborn and even odd, but rarely does one encounter villains of the cardboard cutout variety. Indeed, his latest film, The Wind Rises, is about the decent, hard-working men who created the Mitsubishi Zero, as fine a piece of aviation engineering as any American aircraft of that era.

What Miyazaki’s films teach us is that there are all kinds of people in every society, and decent people can be found in the worst places at the worst of times, despite nationalistic posturing and the daunting social pressure to conform.

[For the full article, see here.]

Leave a Reply