This is the 500th posting for Green Shinto, and I’m happy to say that it’s by one of my favourite writers on Japan, Michael Hoffman. In a piece for the Japan Times, he writes of the role of swords in Japanese culture. Swords of course played a significant role in early Western myths and beliefs – one only has to think of Excalibur to realise that – and in Shinto mythology too the sword holds a symbolic role. It’s one of the three sacred regalia, along with the mirror and the magatama bead, that was supposedly handed down through Ninigi to Jimmu and the imperial line. While the mirror is said to be housed in Ise and the magatama in the imperial palace, the sword ended up at Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya.

In the piece below, Hoffman reflects on the cultural significance of the Japanese sword. (The full article can be accessed here.)

*************************************************

Only in Japan could a sword be ‘life-giving’

Only in Japan could a sword be ‘life-giving’

Michael Hoffman Japan Times

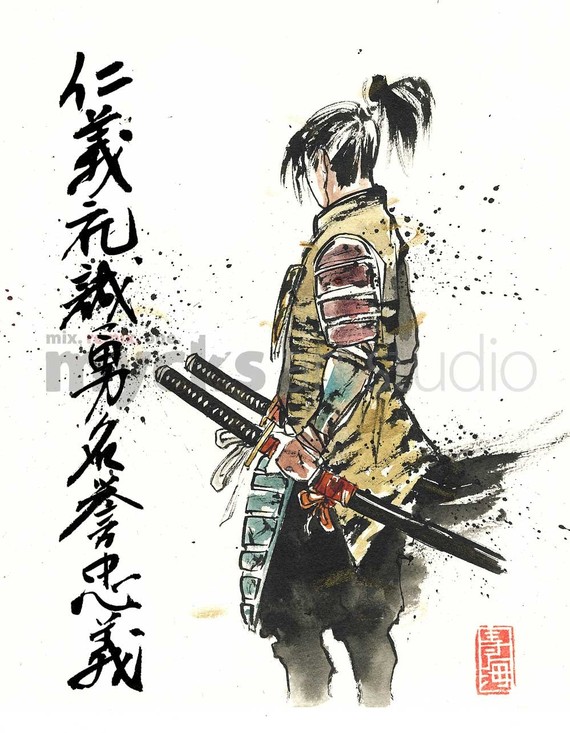

“The sword is the soul of the samurai” — such was the proud declaration down the centuries. It is a weapon common to most early civilizations, but “there is no country in the world where the sword has received so much honor and renown as in Japan,” wrote Yokohama-based English diplomat Thomas McClatchie (1852-86), one of the first foreign students of Japanese martial arts.

The sword figures in the earliest myths. Susano’o, the storm god, slays a people-devouring monster, extracting from its forked tail the sacred sword that became, together with a sacred mirror and a sacred jewel, one of the regalia of Imperial authority bestowed by the gods upon the nation’s first human ruler.

Down to modern times, “The swordsmith was not a mere artisan,” wrote the Christian scholar Inazo Nitobe in “Bushido” (1900), “but an inspired artist, and his workshop a sanctuary. Daily he commenced his craft with prayer and purification.”

The Japanese knew of firearms as early as the 1540s, when Portuguese traders brought them and did a very brisk business selling them. In Japan, though, the gun never displaced the sword, as it did in the West. Why? Numerous material factors can be cited — the shortage of firearms relative to the number of fighters; the unrelenting warfare of the time that favored tried and true techniques over uncertain experimental ones; the inconvenient length of time it took to reload a gun between firings.

But the sense of the sword as more than a weapon — as a “soul” — was surely decisive.

Old Japanese literature — philosophical, religious and military — refers frequently to “the life-giving sword.” Why “life-giving”? The sword is a lethal weapon, none more so than the Japanese sword, whose technical excellence is the marvel of connoisseurs worldwide. No one talks of the life-giving pistol, the life-giving atomic bomb, the life-giving drone. Where is the life in a death-dealing sword blade? The modern mind struggles to understand.

Religion and martial ardor meet in the person of a Zen priest named Takuan Soho (1573-1645). An accomplished swordsman himself, he served as spiritual guide to the outstanding martial artists of his day, whom he taught along such lines as these: “The enemy does not see me. I do not see the enemy. Penetrating to a place where heaven and earth have not yet divided … I quickly and necessarily gain the desired effect.”

That “desired effect” can only be the death of his opponent, but the death of a master swordsman at the hands of a master swordsman, tradition has it, is not death — certainly it is not murder — because the religious enlightenment that is prerequisite for true mastery places one beyond the illusory distinction between birth and death.

“As long as a student of Zen entertains any kind of thought in regard to birth-and-death, he falls into the path of the devil,” explains a Zen master quoted anonymously by Zen priest Daisetz T. Suzuki (1879-1966) in “Zen and Swordsmanship.”

Foremost among Japan’s master swordsmen is Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), who lives on long after death in kabuki, bunraku (puppet theater), novels, manga, movies and television dramas.

Musashi fought his first duel at age 13 and spent much of his life roaming the country matching skills with other masters. Japan’s centuries of civil wars were over by 1615. Peace held until 1894. But the “life-giving sword” was not to be suppressed by peace. Musashi fought 60 bouts in all, most of them fatal to his opponents. Does that make him a killer? Emphatically yes, in the eyes of some. He “elevated killing to a fine art,” writes historian Beatrice Bodart-Bailey in “The Dog Shogun” (2006). “His famous ‘Book of Five Rings’ consists of detailed instructions on how to kill quickly and effectively.”

Bodart-Bailey will have none of the “life-giving sword” mysticism — but Musashi himself wrote, “I was unbeaten because I gave no thought to my life.” He was a dedicated student of Zen; also a poet, tea master, landscape gardener, town planner, writer and painter. To him, the artist was in a state of religious transcendence and all arts were one. Swordsmanship, to Musashi, and indeed to all swordsmen, was an art. In the Japanese tradition there is no “Thou shalt not kill.”

If the 1876 anti-sword law stripped the samurai of their soul, it did not — nor did it intend to — pacify the national spirit. The notion of the “life-giving sword,” extended to embrace modern weaponry, survived into the 20th century. “There is no choice,” wrote Zen scholar Tomojiro Hayashiya (1886-1953) in 1937, “but to wage compassionate wars which give life to both oneself and one’s enemy.”

Congratulations on your 500th blog entry John! I can understand why Michael is one of your favourite writers. This piece is both informative and insightful.