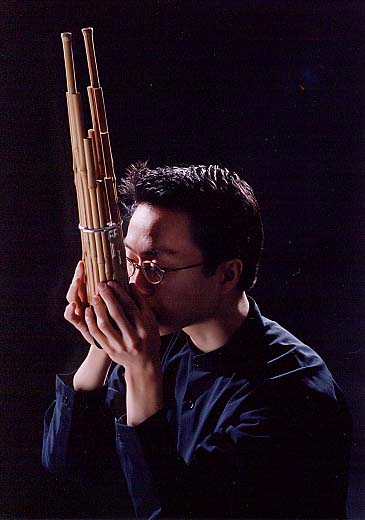

Musical adventurer, Dean Brodrick, who improbably put together a gagaku orchestra in Britain in the 1980s

1) A gagaku orchestra in 1980s Britain seems most unlikely. Can you tell us how that came about?

During the 1980s I was collaborating with musicians from diverse backgrounds, many of whom I had met through association with the LMC (London Musicians Collective). I helped to administrate this collective for most of a decade and was fortunate to meet and play with countless musicians in the free and experimental music scene. It was considered “normal” amongst such pioneers to seek out music from every nook and cranny of the recordable world.

This was a time of enthusiastic ethno-musicological research, a time just prior to the now familiar notion of “world music”. The compact disc had not arrived just yet, and a recording referred to either a piece tape or a piece of vinyl. My friends and I looked particularly outside the regular vistas of pop/rock/folk and classical. We went to the National Sound Archive to seek out the music of the indigenous and obscure folk recordings, field recordings of animals and birds and environments; we huddled around lo-fi records of free jazz and home made improvised music; we thrived on uncommerciality. We developed a taste for dissonance, oddness, and the uncategorizable.

A Japanese musician plays the hichiriki

I was at the Royal College of Art at this time and was exposed to a great deal of performance art, which frequently employed savage and uncompromising musical elements designed to shock and defy cultural norms. Some “members” of this collective even eschewed any conventional melody harmony rhythm or timbre and were even a little contemptuous of mass-produced cultural artifacts. At this time I was working regularly with two great shakuhachi players: Clive Bell and Adrian Freedman. Both had studied in Japan and introduced me to a variety of Japanese musics, one of which was Gagaku.

2) How many members were there and what instruments did they play?

I remember the first time i heard Gagaku. It was on record and i scrutinized the pictures on the album cover, woodcuts and drawings of Bugaku dancers perfoming in a palatial setting to a seated Emperor and his Court. The two hichiriki (oboes) cut through the ceremonial air sounding like air-raid sirens or Amazonian cicadas calling in the night, set against the delicate inhaled and exhaled crushed chords of the two sho (mouthorgans).

Demonstration of how to play the sho (mouth organ)

It was a music which began without apparent tempo, but is in fact lead by the long breaths in and out of the sho, and counts almost exclusively in four. Long intense melodies were suspended within the exotic Japanese Imperial Court tonality over sudden punctuations from a small bright shoko (gong) played with 2 horn beaters; a brittle tight kakko (hour glass shaped drum) played with 2 wooden sticks, and a thunderous tsuri-daiko (bass drum on a stand) hit with a padded stick.

Amid this wailing and clatter I heard the gentle plucked arpeggios of the gakuso (13 stringed zither) and the almost tuneless thwack of wood on wood and gut string which is the biwa (four stringed lute), sounding more like a shuttle on a loom than a guitar. Playing in the same register, and rubbing in microtonal intervals with the two hichiriki were the two ryuteki, (transverse wooden flutes) which created ear splitting difference tones that swooped across the frequency range like the electronic signal one might expect to hear if scrolling though a short wave radio receiver.

By the end of the first piece I had been transported back to eighth-century Japan. The music cut through me like a knife and dissected my brain. ‘Wow!’ we laughed. ‘How about trying to play that?’ we joked. But the joke proved the seed of reality, and apart from myself and Adrian Freedman (hichiriki) the circle of friends that came together to form the group were: Hugh Nankivell and Andrew Okrzeja (sho), Clive Bell and Clair Placito (ryuteki), Melissa Holding (gakuso), Stuart Jones (biwa), Jackie Brooks (shoko), Glen Fox (kakko), and Adrian Lee (tsuri-daiko).

3) How did people get their instruments and learn the music?

Jackie and myself bought fabrics, red silk shot with gold, and trimmings, and copied the designs of the gagaku costume and made one for each of the band. We made hats too and thought we looked amazing!. We went to Ray Mans, the Chinese musical instrument shop in Soho, and bought copies and Chinese equivalents of all the instruments of the orchestra.

Melissa already had a koto so we adapted that. Adrian and myself transcribed the music of several classic gagaku pieces, including Etenraku (which means: ‘music from the highest heaven’). We booked a room to rehearse at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, part of London University). We even asked a photographer to make a publicity photo of us all, posing with our instruments.

Procession of gagaku musicians at a shrine wedding in Japan

Musicians seated on the ground play celestial music, spanning the gap between earth and heaven

*************************************************************************

For Part Two of this article, please click here.

Leave a Reply