Gunther Nitschke, taking time out from his talks for the Ando Institute for a drop of Starbucks coffee

Kyoto is now becoming quite a centre of English-language Shinto studies, and today I happened to run into Gunther Nitchske at my local Starbucks. Gunther specialises in architectural and urban studies, and he is the author of the fascinating From Shinto to Ando: Studies in Architectural Anthropology in Japan (1993).

Thanks to his contacts and professional expertise, Gunther has been able to gain unusual access to Shinto sites and ceremonies. Two of the articles he’s written that I found particularly informative concern the Daijosai ceremony for the enthronement of new emperors and the Miare festival at Kamigamo, which is off-limits to outsiders.

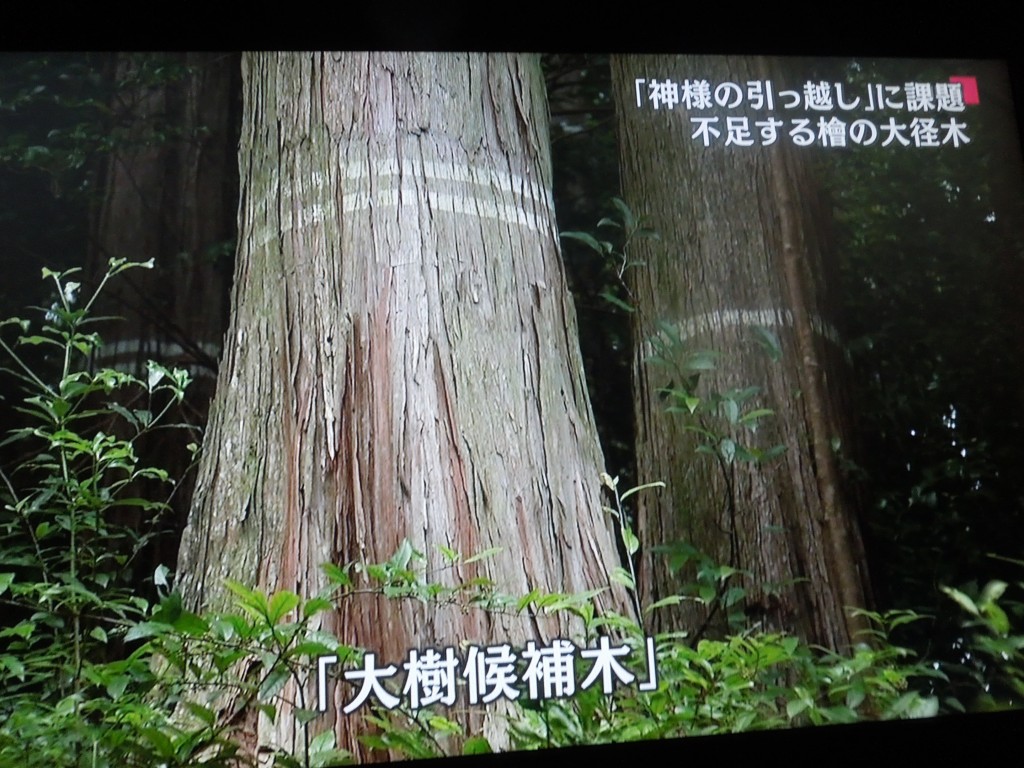

In discussing the recent shikinen sengu at Ise Jingu, Gunther mentioned a couple of interesting points. One was that a grand total of 14,500 trees have to be cut down for the wood needed in the 20-year renewal of the buildings. That’s a staggering amount when you think about it, and makes you wonder just how ‘green’ the renewal might be. Apparently the trees have to be 200 years old and new ones have been replanted this year to be harvested in 200 years time.

Trees, Gunther pointed out, are literally at the heart of the Ise enterprise. Special rites are used when the trees are cut down, and many are transported in special fashion to Ise with villagers and tourists anxious to touch them or get a piece of the bark. And the real ‘heart’ of the shrine, Gunther asserted, was not the goshintai mirror which serves as the spirit-body of Amaterasu, but the shin no mibashira (heart august pillar) around which the new shrine is constructed, though it serves no functional purpose. Presumably this is an example of the axis mundi that in shamanic religions lies between heaven and earth.

A final point worth mentioning from our discussion. In the face of mankind’s basic existential angst at the passing of time, Gunter pointed out that there were two basic responses. One was to build monuments in stone which were meant to last forever, such as the pyramids or the great European cathedrals. These were an attempt to triumph over time by asserting a legacy of permanence. Another way represented by Ise was to use perishable materials but engage in ongoing renewal so as to triumph over decay. This could be seen as working with nature, in the sense of following the pattern of renewal built into the seasonal round.

Wood, trees and drawiing down the spirits are intertwined with the 20-year cycle of rebuilding at Ise

That was verry interesting. But your article, Mister D., doesn’t mention where Mister Nitschke articles were published.

I’m curious about the Daijô-sai. ^^’