This is the third in an ongoing series comparing the pagan pasts and present of Britain and Japan…. For the previous two episodes please click here for Part 1 and here for Part 2. Part 1 compared the two countries in historical times, while Part 2 focussed on Yayoi Japan. Now we look at the British equivalent to the Yayoi influx of immigrants – the arrival of the Celts in the British Isles around 500 BC.

*********************************************************************************************************************************************

Like their Japanese counterparts, the Celts were good farmers, pottery-makers and weavers. Rather than rice, they grew wheat and barley, with a livestock of sheep, goats and pigs. They lived for the most part in scattered farming communities or hill forts surrounded by an earthen bank with wooden fencing and a ditch to keep out intruders.

Model of a Celtic hut at Glastonbury Lake Village

When the Romans arrived around the turn of the millennium, they found a land of Druidism with a study centre on the island of Anglesey. As in Japan, there were clans with their own ancestral gods, whose wish was interpreted by shamanic leaders. Shrines were built next to streams, which were regarded with reverence for their life-giving qualities and seen as a gift from Mother Earth. Animals were sacrificed to harness their power (in Japan horses were presented to the kami). Rituals were held to promote and give thanks for farm produce, in similar manner to the role of rice in Japanese rites.

Ancient Briton had its equivalents too to the three sacred regalia of Japan – the bronze mirror, sword and magatama beads which were handed down by Amaterasu to her grandson Ninigi no mikoto to take to earth. (According to tradition they still exist: the mirror at Ise, the sword in Atsuta Shrine and the magatama in the imperial palace.)

In Briton, highly polished and decorated bronze mirrors were valued for their spiritual power. Swords were regarded as symbols of the warrior to whom they belonged, as if the human spirit had entered into the weapon, and they were ritually buried with their owner. The role of Excalibur in the Arthurian legends clearly owes itself to such beliefs.

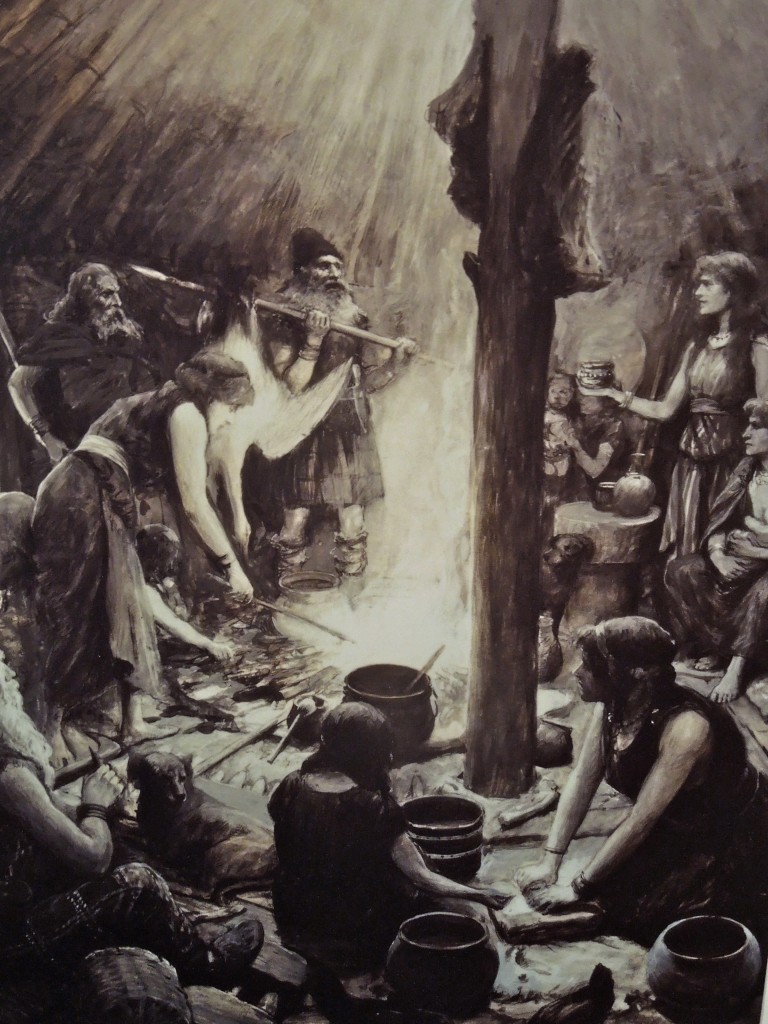

Artist's impression of Celtic life in the Glastonbury Lake Village (300BC - c.100AD)

Offerings to deities were made in both cultures by throwing objects of value into ponds and wells, considered to be openings into the otherworld (the practice is the origin of modern day wishing wells). In Britain cups, shields, swords, mirrors and other precious items have been retrieved by archaeologists from watery depths; in Japan too mirrors and other goods have been retrieved from sacred ponds.

The practice was incorporated into Arthurian legend in the famous passage where Bedivere returns Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake. (Anthropologist C. Scott Littleton maintains that the King Arthur story shares common roots with the Yamato Takeru legend in Japanese myth, especially the use of magic swords and death by an enemy after giving up the sword to a female figure. Littleton presumes a common origin for the stories in north-east Iran.)[1]

As in Japan, the religious practice of the Celts followed an animistic religion in which outdoor worship was performed in temporary structures. People worshipped spirits of nature, often in wooded groves or beside streams and springs. Rituals were carried out by priests called Druids (the name derives from the Celtic word for oak, a sacred tree). The priests wore white robes, as in Japan symbolic of purity, and the training could take up to twenty years. Practitioners were expected to be conversant in law, learning and customs, while bards provided song-poems of epic deeds.

Seasonal festivities were based around the farming lifestyle, which because of animal husbandry had more of a year-round feel than the spring-autumn rites of rice cultivation. The four great Celtic festivals comprised Samhain in autumn, when animals were slaughtered before the onset of winter; Imbolc in early spring, which heralded the time of lambing; Beltane in May, when cattle were sent out to graze between lighted fires; and Lungnasad in late summer, which was held as the crops ripened.

[1] Littleton, C.S. ‘Yamato-takeru: An “Arthurian” Hero in Japanese Tradition’ Asian Folklore Studies Nanzan University Vol. 54, No. 2 (1995), pp. 259-274

Coming from a strong Celtic background and tradition and recently delving into Shinto, it was curiosity that began the search for established links made by others. Thank you. I’m looking forward to delving deeper.