John Breen prior to his talk at Doshisha University for the Asian Studies Group

In a talk this week at Kyoto’s Doshisha University, leading Shinto scholar John Breen talked of postwar attitudes to the Shikinen Shingu rituals at Ise marking completion of the 20-year cycle of rebuilding. In particular, he focussed on the ‘the process of production’ in the 1953, 1973 and 1993 events.

Issues surrounding the event reflect on Shinto as a whole, the main one being whether the enormously expensive rebuilding programme should be funded by the state or through individual donations. The postwar constitution bans state support for religion, but there are those who argue it is more a national than religious institution. (13,000 trees are felled for each rebuilding, and hundreds of precious offerings handcrafted).

In the aftermath of the war, Ise was championed for the 1953 renewal as a cultural heritage in an attempt to distance itself from the legacy of State Shinto. The idea of a ‘people’s Ise’ was not favoured by the shrine establishment however, which emphasised Ise’s imperial rites.

The 1973 renewal saw expression of a move to restore the shrine’s prewar status, and a pamphlet by the fundraising committee said that its ceremonies ‘have inherited, without change, the traditions of prewar Japan’. The ideology was one of Japaneseness, with the shrine said to embody ‘an ethnic creed, a national will, that has always – moreover, naturally and deeply – flowed in the depths of the Japanese heart.‘

Ornamental sword, one of tne hundreds of re-created offerings for the 20 year completion rites

For the first time in recorded history, the number of visitors to the Naiku (housing Amaterasu) outranked those to the Geku (housing the food deity, Toyouke). This may have been due to changing perceptions, but Breen ascribed it at least partly to innovations in the Ise road design, thanks to which access to Naiku became physically much easier.

For the 1993 event another striking development took place, as the emperor not only personally initiated proceedings by asking the chief priest to start the rebuilding programme, but made the first donation to the costs involved. Amaeterasu’s role as imperial ancestress was seen as concomitant with that of protector of the nation as a whole. The official slogan was a haiku which in Breen’s translation reads as, ‘The resurrection/ of the Japanese heart:/ The rite of progress.’

Worshippers climb the steps leading up to the main Naiku building

With the 2013 renewal, the restoration of Ise’s prewar status was further solidified by the attendance of the prime minister and his cabinet – the first time since the 1920s. With the emperor represented by a personal envoy, the message was clear: here was an event not just of significance to the imperial line, but to the Japanese as a whole. Under the nationalist regime of prime minister Abe, Shinto is very much an affair of State.

What is one to make of all this? The best way to contextualise developments would be through a comparison with the past. Is Ise reverting to a time-honoured position, or simply to a post-Meiji situation?

Details of Ise’s historical role will come in a book that Teeuwen and Breen are currently preparing. It promises to be an exciting affair, revealing much that has never been published in English before – nor indeed, I believe, in Japanese.

By the time of the next Shikinen Sengu, we should be much better informed about what exactly is at stake in ‘the process of production’.

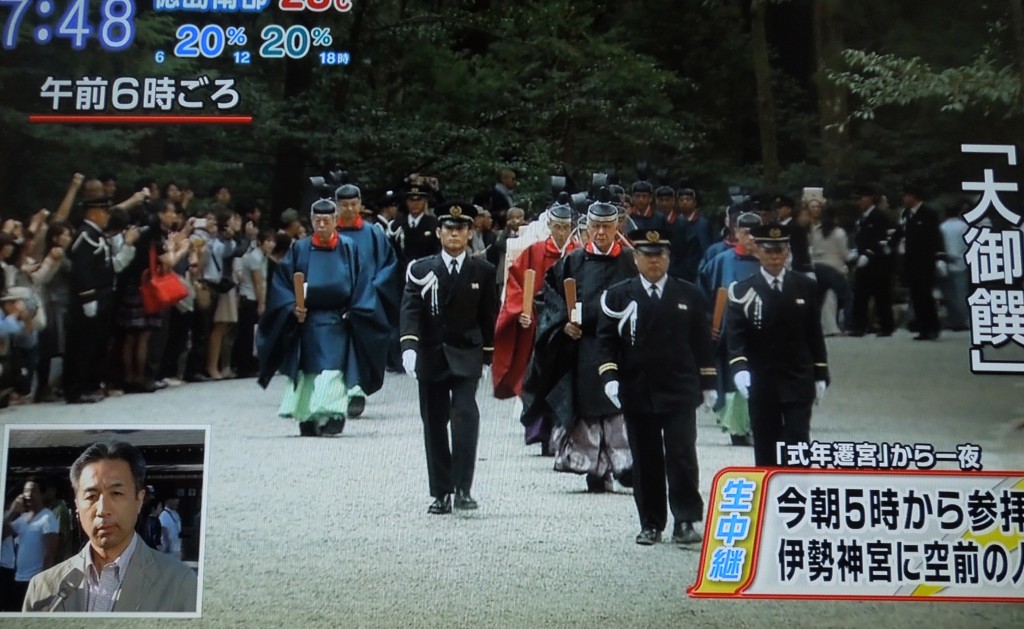

The procession of priests for the shkinen sengu ceremony, as shown on television

********************************************

For a firsthand account of the ‘shikinen sengu’ rites, see the report by Green Shinto reader Peter Grilli here.

Leave a Reply