The International Shinto Foundation has a centre in midtown Manhattan, and in the article below Stacy Smith reports on a purification and explanation session that took place one New Year. It’s instructive not only for what it has to say about purification but about Shinto in general.

**************************************************************

Learning the Meanings Behind the Rituals of Shintoism (by Stacy Smith)

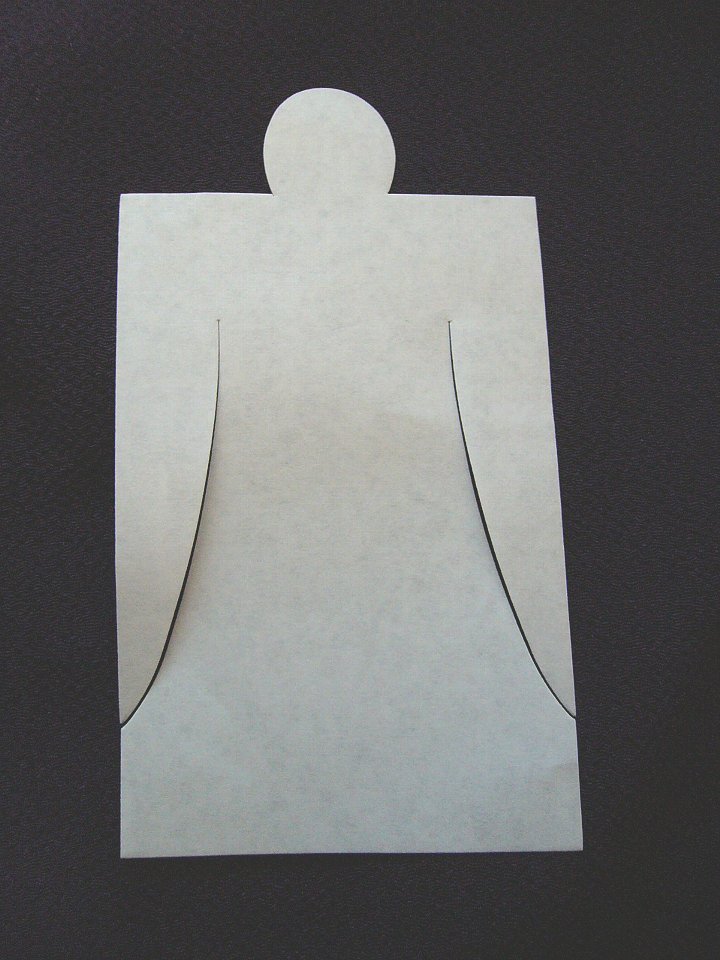

Priest Masafumi Nakanishi purifies the 'hitogata' paper dolls (courtesy ISF)

In the Shinto religion, a large-scale purification ceremony takes place every six months, and this event is held every New Year’s Eve at the International Shinto Foundation in midtown Manhattan. Last year I joined a mixed crowd of about 20 people who were listening attentively to the explanation from Shinto priest Masafumi Nakanishi. He shared how it cleansed participants of the two types of heavenly and earthly sins.

In the ceremony, hitogata (paper dolls), on which you write your name, age and sex, are used to absorb your sins. You can also use them to rub a body part that is ailing you and then blow on the paper three times to eliminate this pain. I passed the paper over my whole body and somehow felt instantly absolved.

Nakanishi then collected the dolls and began their purification before reciting the great purification prayer, or norito, with the group. The ceremony was concluded with a sip of saké for all participants, celebrating the fact that the sins from our respective bodies had been transferred to the paper. Then, Nakanishi will eventually bring the hitogata to Japan, scattering them into pieces and strewing them in a river to finalize the process.

Hitogata paper doll which is rubbed on the body to absorb 'pollution'

In order to learn more about Shintoism, I asked Nakanishi a couple of basic questions and got some surprising answers. This religion is unusual in that one does not need to publicly profess belief in Shinto to be a Shintoist. In Japan, the local shrine automatically adds a child’s name to its list when he/she is born, so people who are Buddhist, Christian, etc. would have to ask to be removed.

Shinto is considered to be a religion with wide interpretations, not one that dictates what its followers should do. As Nakanishi said, “Even though at your household altar you are supposed to give the deities an offering of uncooked rice, if you are moved to give your favorite dishes instead, that’s fine.” He emphasized all that matters is the feelings behind one’s actions.

Despite its lack of prescriptiveness, this is not to say that Shintoism does not have certain rules. For example, when you visit a shrine it is imperative that your mind and body be purified for the gods. Ideally you would bathe at the water basin near the entrance, but since this is not socially appropriate it is recommended that you wash your hands and mouth. At the shrine building, after making an offering (only optional), you bow and clap twice each and then finish with a deep bow.

Visitors to shrines may also buy a fortune known as omikuji. There are five levels ranging from super luck to bad luck, but even if the overall fortune is not to your liking, Nakanishi said it is best to focus on the details of the section (i.e. love, work, academics) that you most care about and take it as advice regarding that. He also added that it is important to think of what you desire before you pick your fortune, as the results will speak to your wish. It is said that the fortune you pick during hatsumoude, a New Year’s visit to the shrine, determines your fate for the upcoming year so people always select very carefully at this time!

I was able to give it a try as there were omikuji at the ceremony, and was happy to get the highest level and a special charm for traffic safety. At the shrine, you can either keep your omikuji or tie it to a branch. I opted for the latter as they had a provisional tree set up at the foundation, but decided to take my charm home.

A stand for fortune slips at Suwa Taisha in Nagano

Leave a Reply