Monkey magic: Saruiwa (Monkey Rock) is a jagged offshore rock resembling a monkey that the gods used

to “peg” Iki Island in place. (Photo Edan Corkill)

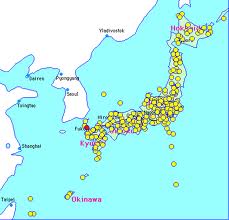

I stopped off once briefly at Iki while island hopping my way from Korea to Japan. There are ferries that go direct between Busan and Fukuoka (Hakata Port), but there are also ferries that stop at Tsushima, close to Korea, then at Iki, closer to Japan.

I didn’t stay long on Iki because I was in a hurry to get on with my journey into the Kyushu mythology of the Kojiki. However, an article in the Japan Times yesterday suggested that I should have. It has one of the largest concentrations of shrines in Japan. Because of its strategic position, it was an important place for stopping off for trade and diplomatic missions between Japan and the continent. And it’s mentioned in the mythology as one of the eight original islands of Japan.

**************************************************

Iki Island: the stones and stories that keep paradise from floating away

BY EDAN CORKILL

Despite its picturesque, rocky coastline, Iki’s geography is characterized by gently rolling hills — the highest peak reaches just 212 meters.

Despite its picturesque, rocky coastline, Iki’s geography is characterized by gently rolling hills — the highest peak reaches just 212 meters.

Architect Kisho Kurokawa took advantage of this landscape when designing the Iki City Ikikoku Museum, which appears to be dug into one such hill. Opened in 2010 (Kurokawa died in 2007, before it was completed), the building is located in Iki’s southeastern corner, about 20 minutes drive south of Ashibe Port. With grass laid over even the top of some of the structure, it would almost be invisible, but for a lighthouse-like observation tower that juts out from the top and, on a clear day, offers views over most of the island.

The museum was built to house Iki’s many prehistoric artifacts. Because of its location between the Chinese mainland and Japan, Iki has long been a stop-off point for traders, and a vibrant human community has existed there for at least 4,000 years.

One of the museum’s key attractions is a series of highly detailed scale models of an Iki village during the Yayoi Period (200 B.C. to A.D. 250). Some of the models are several meters long, and they detail such activities as fishing, trading, playing, hunting and fortunetelling. Many of the characters move at the push of a button and, extraordinarily, all of their faces have been modeled on the faces of contemporary Iki residents.

The museum also houses many artifacts from the slightly later Kofun Period (250-552), which were unearthed at large burial mounds (called kofun) that dot the Iki landscape. These include impressive ornaments for saddles, bridles and stirrups, and also decorative sword handles.

Once you’ve poured over the kofun’s former contents at the museum, you can also stop by the kofun themselves and, in some cases, actually crawl inside.

Kakegi Kofun, which is located in central Iki, appears to be an almost perfect dome — resembling a grass-covered igloo. Entering from a low stone-framed doorway at one side, visitors can move through three separate vaults, each constructed from giant stone slabs. While there is nothing left inside, it is possible to see the stone “coffin” where the body of an ancient Iki citizen — evidently one of nobility or wealth, considering the grandeur of his burial arrangements — once lay.

The primal pair, Izanagii and Izanami, gave birth to eight islands (eight as a number meaning 'a lot' in ancient times). Seven of the islands are strung around the south-west of Honshu, which was the eighth, and were significant as being on sailing routes for the Yamato clan.

Iki has many other attractions of a spiritual nature. In fact the island has a particularly important place in Japan’s Shinto religion. According to the nation’s creation myth, the god-couple of Izanagi no Mikoto and Izanami no Mikoto had eight children, each of whom became the eight “major” islands of the archipelago and, sure enough, Iki was one of them. In fact, as the story goes, little Iki is the older sibling even to Honshu, which is of course now home to Tokyo and more than 100 million people. (For the record, Awaji came first, then Shikoku, Oki, Kyushu, Iki, Tsushima, Sado and Honshu.)

Now the island has one of the greatest concentrations of Shinto shrines (jinja), with 150 in total registered and many more unregistered.

One of the most prominent of the registered jinja is Kojima Shrine, which some have dubbed Iki’s Mont Saint-Michel, because it is situated on a small island that is linked to the main island (in the south) by a thin isthmus that disappears at high tide.

Locals say that not only is the small wooden shrine on the dome-shaped island’s peak sacred, but the island itself is sacred, bestowing good fortune in love to those who visit. But woe betide any traveler who decides to take a branch or rock from the island as a souvenir — misfortune will befall them, the locals warn.

A collection of Jizo at Rokkakudo in Kyoto

Also connected to religious beliefs are seven little jizō (stone statues of a Buddhist deity) that are lined up on a semisubmerged stone plinth at Ashibe, in the island’s east. The Harahoge Jizo, as they are known, are curious because of the small holes in their stomachs. Dozens of stories are told as to why these little beings ended up like this — the holes might have been made to place offerings for ama (diving women) who died at sea — but what is certain is that the little statues like their watery home.

Citing conservation concerns, the local government moved them to dry ground a few years ago, only to be flooded with complaints from elderly locals saying that the jizo had visited them in their dreams asking to be returned to the water. The government complied.

********************************************

Getting there: Ferries and Jetfoils run daily from Hakata Port in Fukuoka to Iki Island (travel time by ferry is two hours 15 minutes). Iki -> Tsushima: 2 hours by ferry. Daily flights also operate from Nagasaki Airport to Iki Airport.

One way prices:

Hakata -> Iki, 3720yen first class, second 2670yen, ordinary 1870yen

Hakata -> Tsushima, 7160yen first class, second 5240yen, ordinary 3580yen

Leave a Reply