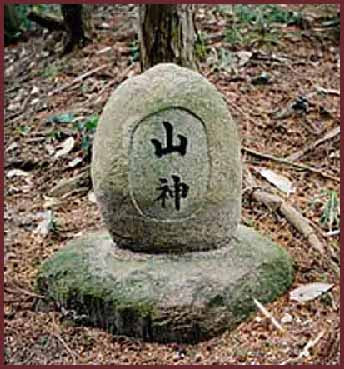

A shrine to Yama no kami (photo by Lee Ratt)

Green Shinto has featured before the writings of naturalist Kevin Short, who combines his research of Japanese flora and fauna with explorations into folklore. In a recent column for the Japan News, which can be accessed here, he writes of the tradition of ‘yama no kami’ (mountain kami) and ‘ta no kami’ (ricefield kami). These are linked to Japan’s rice culture, held to underpin the very essence of early Shinto.

The usual understanding is that the mountain kami morphs into the rice-field kami in spring, descending with the nourishing mountain streams to feed the rice-paddies as it were. In autumn, following the harvest, it returns to the hills where it spends the winter. However, as Kevin Short points out, there is another form of mountain kami which remains in her realm throughout the year. This is the one worshipped by hunters and foresters.

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan*s shrines were realigned along imperial lines and many of the rural shrines honouring nameless ‘yama no kami’ or ‘ta no kami’ were merged into larger entities. Though not so common now, they can still be found however, and the concept remains a living tradition in rural parts as Short’s article makes plain.

************************************************

Man’s survival is an age-old matter of flattering the Mountain Goddess

By Kevin Short / Special to The Japan News August 19, 2014

One of my favorite Japanese folklore themes is the Mountain Goddess and the Devil Stinger. This is a story that is widely told in southern Kyushu, but has similar versions in other areas of the country. The Mountain Goddess, or Yama no Kami, is a Diana-like ruler of lands where men live by hunting wild boar or black bear, or by felling trees or gathering herbs. Men who work in the mountains revere the Yama no Kami as the ultimate life force animating the forests and the plants and animals that live there.

The great storywriter and folklorist Muku Hatoju once accompanied a traditional wild boar hunter on a trip deep into the mountains along the border of Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures. “The wild boars we hunt do not belong to us.” The old hunter explained. “They belong to the Mountain Goddess. When we go boar hunting, we humbly ask the goddess to share some of her bounty with us.”

A yama no kami marker (courtesy fudosama.blogspot - see link below)

But ruling over the mountains and forest creatures are not the Mountain Goddess’ only task. In early spring, when the rice paddies are ready for planting, she morphs into the Ta no Kami or Rice Goddess. The Goddess leaves the mountains and takes up residence on the dikes between the paddies. Here she stays, watching over the precious rice crop, until the harvest is completed in early autumn. Then she returns to her mountain domain.

Rice farmers usually engage in celebrations, including dancing, music and sometimes theater, to welcome the Goddess into the paddies in spring, and to send her back to the mountains in autumn. The Mountain Goddess is a folk superheroine that blesses the lives and livelihoods of both rice farmers and traditional mountain folk.

In Japan, local kami are asked or thanked for their blessings with food, drink and entertainment. Beautiful fish, such as pink sea-bream (tai) are favored by most kami. The Mountain Goddess, however, must be handled with extreme delicacy.

Although kindhearted and with a true feeling of empathy for the people, she is subject to fits of almost manic depression, during which the natural order begins to break down in both the mountains and the paddies.

The Mountain Goddess gets particularly despondent about her looks. She is, if you will, a bit funny looking. If you presented her with a sea bream, she would only feel sadder; because the beautiful fish would stand in sharp contrast to her own strangeness. The only way to coax the Goddess out of a funk is with a fish that makes her feel better about herself. To qualify, the fish would have to be even stranger-looking than the Goddess.

Devil Stinger found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans (courtesy oceanwideimages)

The fish selected for this grave honor is the oni-okoze, called Devil Stinger in English. The oni-okoze is one of a dozen or so species of very similar-looking fish in the genus Inimicus, found in the warm tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific region. All these fish are ambush predators. They lie camouflaged on the ocean floor until a smaller fish passes close, then thrust upwards at incredible speed. The passing fish is sucked into a wide vacuum-cleaner mouth, and swallowed whole before it even realizes what happened!

The oni-okoze is truly one very strange-looking fish! The heavy body is designed to lay still either on the ocean bottom or just inches above it. The huge, bulging eyes are on top of the head, and the big mouth opens nearly straight up. Bits of skin hang down from the jaws and face, made to look like pieces of algae attached to a rock. The lower two rays of the pectoral fins can rotate freely, and are used as stiltlike supports for “walking” along the sea bottom.

To protect themselves, devil stingers are armed with a row of long, hard, sharp spines along their dorsal surface. These spines can be made to point straight upward and contain very powerful poisons in sacs at their base.

Swimmers and divers sometimes accidentally step on or touch camouflaged oni-okoze. Poison symptoms range from excruciating pain and severe swelling and reddening, to partial paralysis, and even to breathing difficulty and eventual heart failure.

In Japan the oni-okoze live from inshore up to about 200 meters deep, as far north as Niigata and Chiba prefectures. The devil stinger is considered to be delicious, and in some areas is even raised in aquaculture pens.

A phallic looking yama no kami in Niigata (Wikicommons)

Depictions of the Yama no Kami are rare, but stone statues of the Ta no Kami are common throughout the rice paddy countryside of eastern Kagoshima and southern Miyazaki. An amazing chance to see four of them in Tokyo is in front of a small Suitengu Shrine at Ikebukuro Ekimae Park, just a short walk northeast from Ikebukuro Station.

Ta no Kami usually carry a rice ladle and a bowl of steamed rice. They wear unusual hoods or hats that are actually part of a neat deception. Viewed from behind, the hood or hat becomes the head of a classic male phallic symbol. The wish embodied in the stones is for fertility and abundance, not only in the rice paddies, but in the farmers’ homes as well.

“”””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””

Short is a naturalist and cultural anthropology professor at Tokyo University of Information Sciences.

For more on Ta no kami and Yama no kami, see http://fudosama.blogspot.jp/2006/04/ta-no-kami.html

Leave a Reply