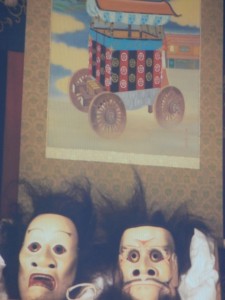

A festival tengu, remnant of Japan's early shamans

A news item recently caught my attention relating to the world’s oldest pair of trousers, found on some Chinese skeletons. The trousers were thought to be those of shamans.

It’s thought shamanism was widespread in early cultures, and Plato wrote in Phaedrus that ‘the first prophecies were the words of an oak’ (interestingly, this was the sacred tree of the Druids). Ancient people used to listen to an oak, or even a stone, he claimed, ‘as long as it was telling the truth’. Hah!! I like that!

Shaman masks now treated as 'treasures' of the Gion Matsuri

In the shamanic world there are ancestral spirits which watch over their descendants, and their are spirits in nature which inhabit animate or inanimate objects. The shaman is a person with special gifts able to mediate between the material world and the spirit world, typically in the form of trance or possession.

Shamanism developed with hunter-gatherer tribes and herding societies. With the move to agriculture, different forms of religious expression evolved which were more stratified and codified. In a paper on the subject, Dean Edwards writes that ‘A society may be said to be Post-Shamanic when there are the presence of shamanic motifs in its traditional folklore or spiritual practices which indicate a clear pattern of traditions of ascent into the heavens, descent into the netherworlds, movement between this world and a parallel Otherworld. Such a society or tradition may have become very specialized and recombined aspects of mysticism, prophecy and shamanism into more fully developed practices and may have assigned those to highly specialized functionaries.’

As Joseph Campbell has pointed out, with a settled existence shamans lose their power and ritualists take over, more concerned with social order and stability. These priests become organs of state, with a vested interest in support of the ruling class. Those with direct access to unruly spirits are demoted and reduced to the role of magicians, or marginalised to the mountains.

Spirit clothes, used in Korean shaman ceremonies

Something of the kind clearly happened in the case of Shinto, where kami are summoned by formal requests by licensed priests rather than induced by trance. The divine voice expressed once in oracle is now sold through fortune slips. Female shamans possessed by kami have been transformed into sales girls selling amulets and performing stately dances. It’s evident too in the animal statuary of Shinto. Power animals once helped the shaman in the transition between worlds – ‘memories of their animal envoys still must sleep, somehow, within us,’ says Campbell. Now they stand as immobile guardians at shrines, fossilised in stone.

In the taming of Shinto, I can’t help thinking there’s something of the Japanese penchant for taming (human) nature. Control, ritual and orderliness is the Japanese way. As Alex Kerr has pointed out in his book Dogs and Demons, the common boast of having a special connection with nature can mean in practice a cut flower in a tokonoma – contained and framed. Shamanism by contrast is much too wild!

Shaman dance in Jeju, Korea where shamanism remains a living tradition

Leave a Reply