Photo courtesy raynoah.com

Mountains are a vital part of Japan’s identity. They are also a fundamental part of the country’s spiritual heritage. Mountain worship is widespread across East Asia, and recognition of their sacred qualities has long been part of Chinese and Korean culture. Physically they reach up towards heaven, and figuratively they draw the human spirit closer to the divine. Many people have written of their inspiring nature, and how mountain climbing brings one closer to the awesome wonder of life. Shugendo (mountain asceticism) has made ‘entering the mountains’ a religious rite.

For Shinto, mountains play a special role in being the abode of kami. Some are even worshipped as kami themselves. Many shrines are placed at the base of mountains, with their Okunoin (Inner Sanctuary) higher up or on the summit. It’s usually where worship on the mountain began.

In the piece below, a Yomiuri staff writer goes in search of the self, which in essence means rediscovering the nature of human nature. You don’t need to be a religious nut to appreciate the spirituality of mountains. You just need the right attitude and a pair of boots. As the old saying goes, one mountain many paths….

*********************************************************

By Takashi Oki Japan News August 31, 2014 (Photos below taken from the original article)

SAIJO, Ehime—Mt. Ishizuchi is a sacred mountain where Kobo-Daishi (774-835), the high-ranking priest who established the Shikoku pilgrimage, trained. Today, many ascetics, conspicuous in white robes, come together to reach its 1,982-meter summit in early July, when rituals are held during a ceremonial opening of the year’s climbing season.

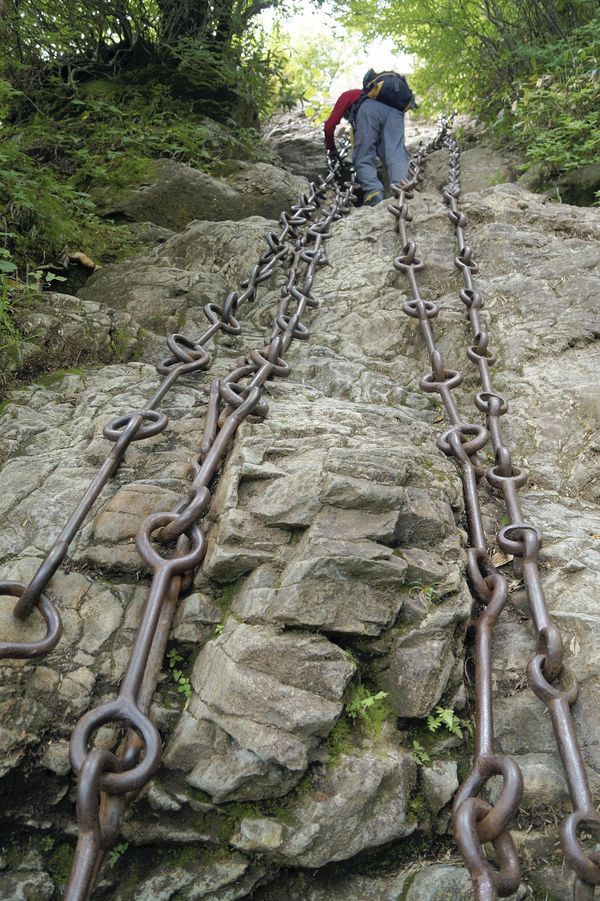

The mountain, the tallest in western Japan, is particularly known for its climbing route with several sets of heavy metal chains dangling down a rocky cliff path leading up to the summit. In “Eien no Ko,” a novel by Arata Tendo, children seeking spiritual salvation struggle to climb the mountain by gripping the chains for support. I decided to reach the summit myself, hoping to find a different self there.

The Ichi no Kusari set of chains dangles on the cliff. There are four sets of chains for climbers on Mt. Ishizuchi, including Tameshi no Kusari (test chains).

On July 17, I visited Saijo, Ehime Prefecture, at the foot of the mountain. To build up stamina for climbing the next day, I ate a popular pasta dish called Teppan Napolitan, a local specialty that is served on a hot iron plate.

At 8 a.m. the next morning, I took the day’s first ropeway service to Ishizuchi Shrine’s Chugu Jojusha, one of the shrine’s worship facilities, located 1,450 meters above sea level. Unfortunately, clouds hid the summit from view.

I began climbing from there, my mind on the weather. After climbing for about 90 minutes through a beech forest, I reached the Yoakashi-toge mountain pass about halfway up the mountain. The forest ended here, and my field of vision suddenly expanded. “You can see the summit,” nature observation guide Yoshiyasu Imagawa, 38, said excitedly. I had asked him to climb with me.

Seeing such a dignified mountain, I felt refreshed and invigorated, ready to climb to the summit. Climbing a little farther, we reached Ichi no Kusari, and the first set of chains running down the side of a cliff came into view. The thick chains run 33 meters down the cliff. Each link in the chain consists of a short iron rod with a ring a little larger than 10 centimeters in diameter at each end.

Gripping the rings one by one while groping around for toeholds, I climbed up the cliff little by little. It was tough for my arms to support the weight of my backpack and my own body, which has a little too much extra fat.

During the climb, I looked down and was seized by fear. It felt like I was dangling from the cliff. If I lost my grip and my feet slipped, I would fall straight down. The thought made me so frightened that I held fast to the chains with both arms. It is said that even primary school children can climb, but it felt almost impossible for me. I managed to finish the climb, but when I reached the top of the cliff, I felt dazed. I may have pushed myself too hard.

In Saijo, Ehime Prefecture, there are many artesian wells called uchinuki. Their water originates from Kamogawa river, some of the water in which originates on Mt. Ishizuchi, infiltrates underground, accumulates and springs up in the wells due to positive pressure.

After a while, we reached Ni no Kusari, the second set of chains. These run as long as 65 meters. “The part we can’t see down here is difficult to climb,” Imagawa said. I gave up on climbing this part. Fortunately, however, there is a detour route for climbers like me.

San no Kusari, the final set of chains, was under repair. I was relieved to hear it and continued going on the detour route. I saw some pretty flowers along the route, and Imagawa told me their names are ishizuchi mizuki and miyama daikonso. “Ryu-ryu-ryui, ryu-ryu-ryui,” cried a bird in the distance. “It’s the meboso mushikui [arctic warbler]. I hope we can see it,” Imagawa said, looking for the bird among the trees.

About two hours and 45 minutes after climbing from Jojusha, we finally reached the summit. Although it was not clear and sunny, I could see a foggy range of mountains in the distance. “I did it!” I found myself crying out.

At the shrine’s Okunomiya Chojosha worship facility in the summit area, I saw Atsuki Yamashita, 60, and his wife Riemi, 59, being given an incantation. Yamashita told me that he had just turned 60 on the day. “I wanted to start a new life at Ishizuchi,” he said.

However, I had further to go in seeking my new self—Tengudake peak, which is the true highest point of Mt. Ishizuchi, which can be seen just across the summit area. It projected sharply through the fog like a fang.

The route from the summit area to Tengudake was rocky, but I had no alternative than to just keep going. I slithered forward little by little on my stomach on the rocky path. I knew it was pathetic for me to be so full of fear while climbing, but I couldn’t help it. After a while, however, I finally reached Tengudake. When I stood at the highest point of western Japan’s tallest mountain, my surroundings became enshrouded in mist, enveloping me in what felt like a divine atmosphere.

I realized I can’t change myself so easily, but I found myself fully enjoying a sense of accomplishment all the same.

Travel tips

Iyo-Saijo Station, near the foot of Mt. Ishizuchi, is about 105 minutes from Okayama Station by express train. Visitors who fly into Matsuyama can reach Iyo-Saijo Station from Matsuyama Station in about an hour by express train. To climb Mt. Ishizuchi from Matsuyama, there is also a route from the Tsuchigoya starting point of the trail up the mountain. For more information, call the Saijo City Tourism Association at (0897) 56-2605.

Hi John, I’m not one to believe in coincidences. Your last two posts have both had strong connections with Shikoku. At the same time that I happen to be reading ‘Japanese Pilgrimage’ by Oliver Sattler. A story that describes the 88 temple pilgrimage on Shikoku. It’s an excellent read. Shikoku is the only one of the four main islands of Japan that I haven’t visited. Something tells me that I should. Interestingly, Deguchi Onisaburo equated Shikoku with Australia in his world map. Another reason to go there perhaps?

Hi there, Jann… Since you posted your comment, there has been another blog item about Shikoku so I guess that it must be calling to you pretty loudly by now. Not sure why it would equate to Australia, but that’s something you may be able to figure out from down under… Friend Amy Chavez has written a book about running the 88 temple pilgrimage, and another friend Ted Taylor has finished a manuscript about it, I believe. I also have another friend Steve Wolfe, who has done the pilgrimage three times I believe, including in reverse order. Perhaps you’ll have to set aside a couple of months for your next visit to Japan, Jann!

The full 88 temple pilgrimage is one of those activities I’ll probably experience through reading rather than actually doing it! We’ll see. I’d still like to visit Shikoku though – one place I’d particularly like to see is the temple with the rock carvings close by. It would be special to see all of the elemental gorinto expressed that way. Visiting Shikoku may also help tease apart why it was associated with Australia all those years ago.