A Hollywood production; a living scroll; an eye-popping kaleidoscope of costumes; a celebration of heritage – Kyoto’s Jidai Matsuri (Festival of Ages) is all this and more. It takes place on Oct 22, and such is the enormity of the event that preparations are already under way.

An article yesterday in the Japan Times brings to light the sheer size of the festival and the elaborate care that goes into the costumes and make-up. The historical pageant is a magnificent tribute to the ancient capital, but what does it have to do with religion? Ah, there’s the rub… It’s a question that brings up the shamanic roots of Shinto and its concern with fostering the cultural heritage of the nation. In celebrating the Festival of Ages, Japanese are celebrating their roots.

As Shinto spreads abroad, it’s an aspect of the religion that is sure to raise some interesting issues. Non-Japanese may wear yukata to carry mikoshi in the style of the Japanese, but whose culture and whose heritage will they be celebrating in their festivals?

**********************************************************************************

Ladies in medieval-style clothing | by Angeles Marin Cabello

Jidai Matsuri: Sad-eyed lady at the festival of the ages

BY STEVE JOHN POWELL AND ANGELES MARIN CABELLO

SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES OCT 4, 2014

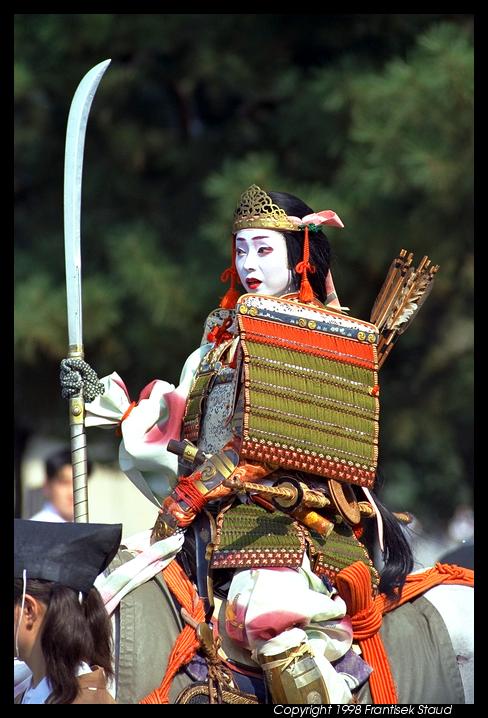

The young lady sitting on the bench nearby straightens her wig and applies the finishing touches to her makeup — face porcelain-white, lips blood-red and heart-shaped. She is wearing multiple kimono, one on top of the other, and must be boiling. It’s only 10.30 a.m., but already it feels like a stifling 30 degrees Celsius. It may just be my imagination, but her countenance seems to hint at some inner torment. What secret sorrow haunts this sad-eyed lady of the lowlands? The answer is as poignant as it is surprising.

To her right, a couple of men dressed as samurai warriors take off their helmets, sit down and tuck into multicolored bentō (boxed lunches). From time to time their horses whinny with impatience.

All around us, benches are laden with swords, quivers full of arrows, helmets, animal skins and rope sandals. Beyond the benches is a profusion of carts, carriages, large tansu (wooden chests), even a couple of oxen. I feel like we’re on the set of some Cecil B. DeMille historical epic.

(courtesy ishama.com)

In a sense, we are, but this isn’t Hollywood. We’re in the vast gardens of the Imperial Palace in the ancient city of Kyoto, where people are gearing up for the annual Jidai Matsuri — the festival of the ages. Along with the Gion and the Aoi festivals, it’s one of the three most important events in the city’s calendar.

The Jidai Matsuri was first held on Oct. 22, 1895, to inaugurate the completion of the magnificent Heian Shrine and celebrate the 1,100th anniversary of the day when Emperor Kammu entered Kyoto in 794 and established the city as the capital of Japan, back when Kyoto was known as Heian-kyo (literally, “capital of peace and tranquility”).

The shrine was built to worship the deified spirits of both Emperor Kammu, Kyoto’s first emperor (who reigned from 781-806), and Emperor Komei (reigning from 1846-67), the last emperor to sit on the throne in Kyoto before the capital was relocated to Tokyo in 1868, at the start of the Meiji Restoration.

“The people in Kyoto felt sad over the removal of the Emperor at that time,” journalist and Kyoto resident Masahiro Nakata tells me. “This was a nostalgic moment for them.”

Aside from commemorating the building of Heian Shrine, the Jidai Matsuri was also conceived as a morale-booster to raise the spirits of the people, still dejected after having their capital city status and Imperial Court taken away. The matsuri thus became a celebration of Kyoto’s glorious heritage, with participants in the parade dressed in sumptuous costumes representing the evolving historical periods of the city’s 1,100-year-long reign as Japan’s capital — from 794 to 1895.

The Jidai Matsuri started as a modest event with just six sections representing six era’s from Kyoto’s history, but it has grown in size and popularity with residents and visitors alike. Today, there are around 20 sections and more than 2,000 participants, who form a 2-km procession that wends its way along a 4.5-km route from the Kyoto Gojo, or Imperial Palace, to Heian Shrine. It’s due to start at noon, and won’t arrive at Heian Shrine until around 2:30 p.m.

In the words of Friedrich Nietzsche: “It is autumn all around, and clear sky.” My wife, Angeles, and I are surrounded by men, women and children dressed in an eye-popping kaleidoscope of costumes as we stand under the welcome shade cast by the towering ancient pine trees in the grounds of the palace — which was the Emperor’s residence when Kyoto was capital. The participants’ elaborate silk robes glisten in the morning sunshine, and some make final adjustments to their garments.

(courtesy Frantisek Stoud)

As a fashion designer, Angeles is thrilled by all this sartorial satori (sudden enlightenment) — “I’ve never seen so much silk!” she exclaims. “And in such lovely, vivid colors.”

Indeed, it’s like being backstage at a David Bowie concert, circa 1972. Except it’s far more sedate. Here, the multicolored multitude quietly chat and sip green tea as they wait.

Meanwhile, a swarm of photographers bobs and weaves among them, cameras clicking away. Angeles joins in and does the same. Yet no matter how many times the participants are called on to face this way or that, they respond with unfailing good cheer, like actors on the red carpet. And just like actors, they are constantly in character. When asked for a picture, they don’t smile and flash the peace sign, but pose with all the dignity and bearing of their social rank. Participants practice wearing their costumes for weeks before the festival, which can only be worn in public on the day of the parade.

With noon approaching, the park is quickly filling up with people hoping for prime viewing spots. Many are already seated on blue tarps along both sides of the wide, gravel driveway. Luckily, we have tickets for seats on the raised viewing platform — row 2, seats 28 and 29, again, just like a concert, a perfect spot from which to enjoy the parade. As we show our tickets, a pretty girl in a uniform hands us a pamphlet.

“How many people are you expecting today?” Angeles asks.

“Around 150,000,” she says.

Finally, the procession gets underway, emerging slowly from the grounds of the palace and out onto the streets of Kyoto. It’s only now that we begin to appreciate the stunning scope of the event. The parade is divided into sections representing each historical period, starting with the Meiji Era (1868-1912) and ending with the Heian Period (794-1185); it’s like watching a living history of Japan scroll past us.

The whole procession takes an hour and a half to pass by. Every imaginable rank and office from 1,000 years of Japanese society is represented here: from emperors and their consorts, courtiers, nobles, commanders and samurai warriors to flower-sellers, foot-soldiers and servants. There are artists, armies, oxcarts, palanquins, horseback archers and more than 70 horses, which trot past with dressage-like elegance.

(courtesy mboogiedown)

The astonishing accuracy of each period’s costumes beggars belief. Clothes, footwear and hairstyles have all been faithfully reproduced in painstaking detail. Even the dyeing of the costumes is done in the traditional way. Everyday objects and military weapons, such as the long-handled samurai swords or Meiji Era rifles, are equally authentic.

Yet, the Jidai Matsuri is far more than a parade of historical garments. Beyond the gorgeous costumes and authentic artifacts, the procession also displays a touchingly human face, thanks to the inclusion of real-life historical characters from each era. These range from the two renowned authors of the Heian Period — Murasaki Shikibu (who wrote “The Tale of Genji”) and Sei Shonangon (“The Pillow Book”) — to the great 16th-century lord and warrior Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

And what of the sad-eyed lady, the one we saw putting on her makeup at the start of this story? She turns out to be Kazunomiya, the poet princess, half-sister of Emperor Komei, one of the two Emperors honoured in Heian Shrine. Her tale is one of the most touching of all the characters in the parade. When she was just 16, her family broke off her engagement to a childhood friend, Prince Arisugawa Taruhito, and forced her to marry shogun Iemochi Tokugawa, in an attempt to unite the Imperial Court and the Shogunate in the era when the Meiji Restoration was rapidly changing Japan.

Belying her tender years, Princess Kazunomiya initially refused the arranged marriage and only acquiesced after insisting on certain conditions. In Kathryn Lasky’s novel about the princess, “Prisoner of Heaven,” Kazunomiya declares, “No matter how they cut me up to serve their purposes, within me there shall always remain a little spark, a small piece that is my essence and cannot be destroyed.”

Princess Kazunomiya’s half-brother, Emperor Komei, together with Emperor Kammu — the last and the first emperors to reside in Kyoto — bring the Jidai Matsuri to an emotive conclusion, as two mikoshi (portable shrines) containing their spirits are paraded through the streets.

Yet for all its pomp, this is very much a people’s festival. It is said that if you ask one student from Kyoto University to volunteer to help with the preparations, 100 will immediately offer their services. As a result, the world can still marvel at Kyoto’s proud history and heritage — a century after it ceased to be Japan’s capital — in this magnificent pageant that captures the soul of the city.

Leave a Reply