Prime minister Abe, campaigning in white gloves to show 'purity' (courtesy Reuters)

News comes today of the resounding re-election of prime minister Abe Shinzo, a self-declared nationalist. He and his supporters, who include both conservatives and those on the far right, promote what are called ‘Shinto values’ in a nostalgic wish to return to the state religion of prewar times.

These right-wing politicians belong to the Shinto Association for Spiritual Leadership, which has an office in the Jinja Honcho building (Association of Shrines). An article in Saturday’s Japan Times illustrates how closely connected it is with the agenda of the resurgent rightwing, and how worrying this is for those who favour tolerance, reconciliation and international harmony.

*****************************************************************

Abe’s base aims to restore past religious, patriotic values

by Linda Sieg Reuters

As Prime Minister Shinzo Abe promises voters a bright future for Japan’s economy, key parts of his conservative base want him to steer the nation back toward a traditional ethos mixing Shinto myth, patriotism and pride in the ancient Imperial line.

Proponents say such changes are needed to revive important aspects of Japanese culture eradicated by the U.S. Occupation after World War II and to counter modern materialism.

Critics say they mirror the Shinto ideology that mobilized the masses to fight the war in the name of a divine emperor. The legacy of that war still haunts ties with China and South Korea nearly 70 years after its end.

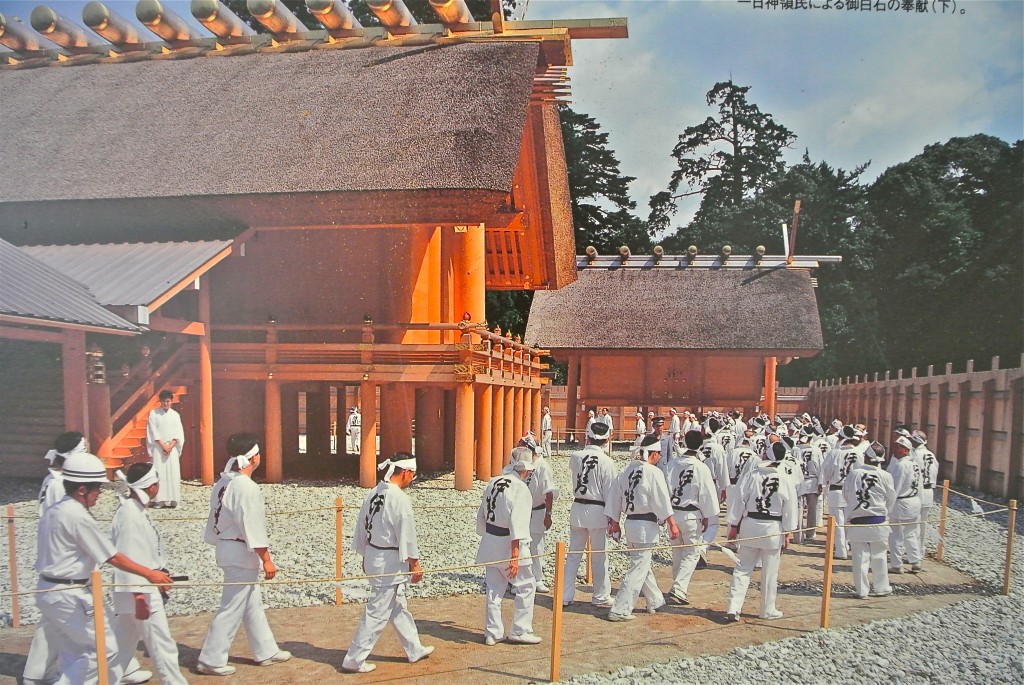

One of the ceremonies in last year's Shikinen Sengu renewal at Ise Jingu. Prime minister's Abe's attendance carried huge political significance.

A predicted landslide win by Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party in Sunday’s general election, which is being called a referendum on his economic growth policies, and prospects Abe may become a rare long-term Japanese leader have given his ardent supporters their best chance in decades of achieving their goals.

“We really have trust in him,” said Yutaka Yuzawa, director of the Shinto Association of Spiritual Leadership, or SAS, the political arm of the Association of Shinto Shrines. The group, which counts Abe as a member, is one of a network of overlapping organizations sharing a similar agenda. “The prime minister’s views are extremely close to our way of thinking,” Yuzawa said in an interview.

Among the key elements of the SAS agenda are calls to rewrite Japan’s U.S.-drafted, postwar Constitution, not only to alter its pacifist Article 9 but to blur the separation of religion and state. Education reform, to better nurture love of country among youth, is another top priority.

“After the war, there was an atmosphere that considered all aspects of the prewar era bad,” Yuzawa said. “Policies were adopted weakening the relationship between the Imperial household and the people . . . and the most fundamental elements of Japanese history were not taught in the schools.”

Similar concerns drive other organizations such as Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), a broader lobby group for which Abe serves as a “supreme adviser.” Experts see parallels between these groups and the U.S. Tea Party movement, with its calls to restore lost American values.

“Nippon Kaigi and the Shinto Association basically believe the Occupation period brought about . . . the forced removal of Shinto traditions from public space and public institutions,” said University of Auckland professor Mark Mullins. “For them, this was authentic Japanese identity . . . and to be an independent and authentic Japan again those things need to be restored.”

Yasukuni Jinja. PM Abe has made prime ministerial visits to the shrine a test of nationalist virility

Abe has long been close to such groups, but they have increased their reach since his first 2006-2007 term as leader. Membership data show 301 members of the Diet, mostly from the LDP, are affiliated with SAS, including 222 in the 480-seat Lower House before the dissolution. A Nippon Kaigi caucus had 295 members, including some opposition MPs. Members of the groups are central to Abe’s administration.

Nippon Kaigi supporters accounted for 84 percent of Abe’s Cabinet after it was shuffled in September and almost all of the ministers were affiliated with the SAS. Eighty-four percent also belonged to a separate caucus promoting visits to Yasukuni Shrine, seen by critics as a symbol of Japan’s past militarism.

Abe’s December 2013 visit to Yasukuni sparked outrage in Beijing and Seoul. Far less attention was paid to what some see as his equally symbolic participation in October that year in a ceremony at Ise Shrine, the holiest of Japan’s Shinto institutions.

The ritual is held every 20 years, when Ise Shrine is rebuilt and sacred objects representing the Emperor’s mythical Sun Goddess ancestress are transferred to the new shrine. Abe became only the second prime minister to take part in the centuries-old ritual, and the first since World War II. “Without anyone blinking an eye . . . it became a state rite,” said John Breen, a professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto, commenting on Abe’s participation.

The far right are firmly behind Abe's desire to promote love of country and prewar 'Shinto values'

The lobby groups are also active at the grass roots. On Oct. 1, they launched the “People’s Council to Write a Beautiful Constitution” to boost support for revising the charter in 2016.

Amending the Constitution faces big hurdles even if the LDP succeeds in winning two-thirds of both chambers, since a majority of voters must then approve the changes in a referendum. But other parts of the conservative agenda are moving ahead, such as making “moral education” part of the official school curriculum with government-approved textbooks, a change slated to take effect in 2018.

That follows a revision to a law on education during Abe’s first term to make nurturing “love of country” a goal.“ Things related to patriotic education are getting pushed through and institutionalized so they are shaping the next generation, whether parents know or think about it or not,” the University of Auckland’s Mullins said.

Leave a Reply