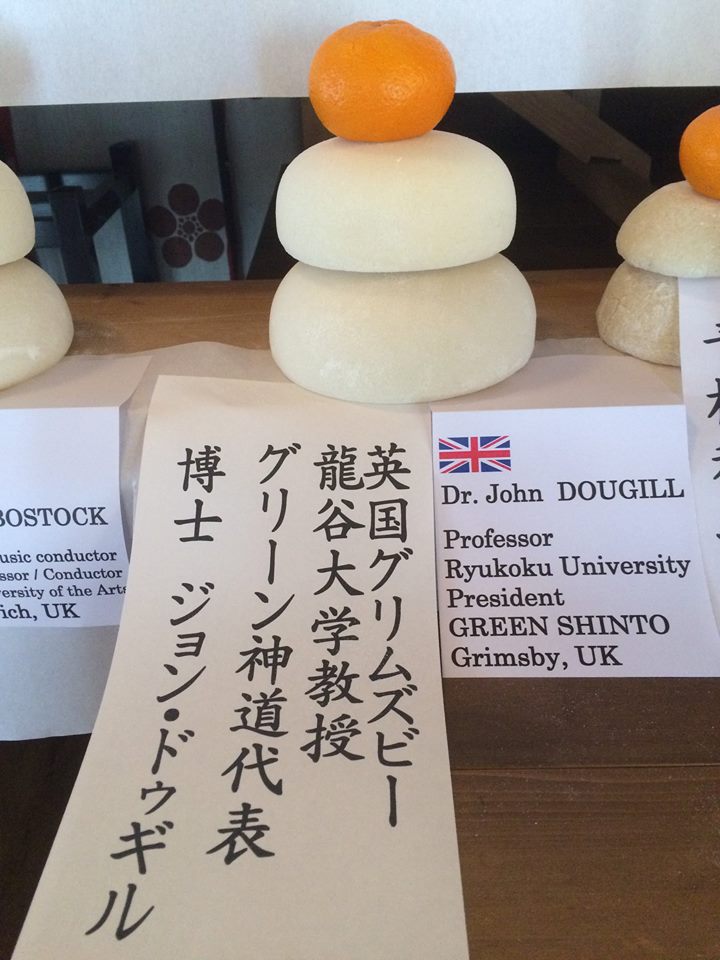

Kagami mochi offered to the kami at Yabuhara Jinja in Nagano Prefecture

Kagami mochi (mirror rice cake) is traditionally associated with the New Year. It consists of two rice cakes, a small one atop a larger one, surmounted by a daidai bitter orange. Rice was traditionally Japan’s sacred food, and it’s thought mochi was a food which gives strength for the coming year. It is offered to the kami in homes and shrines, and Green Shinto is delighted this year to have been honoured by the Yabuhara Shrine with a kagami mochi in the name of its owner, John Dougill. Also honoured was conductor Douglas Bostok, whose Shinto interests and altar were featured in an earlier posting. Our thanks to Masatsugu Okutani for this special privilege, who writes as follows:

Kagami-Mochi is the round shaped rice cakes which are traditionally offered to sanctuaries in Japan on the occasion of the New Year to wish all the happiness and good health among families (“Kagami” means mirror, and the white color of round rice cakes indicate pureness). This year, there were Kagami-mochi offerings from France and UK which is the first time since the foundation of the sanctuary in 680. We thank you very much for all the offers from France and UK as well as local offers.

****************************************

Wikipedia has this to say on the subject:

The kagami mochi first appeared in the Muromachi period (14th-16th century). The name kagami (“mirror”) is said to have originated from its resemblance to an old-fashioned kind of round copper mirror, which also had a religious significance. The reason for it is not clear. Explanations include mochi being a food for sunny days, the ‘spirit’ of the rice plant being found in the mochi, and the mochi being a food which gives strength.

A kagami mochi offering from France at the Yabuhara Jinja

The two mochi discs are variously said to symbolize the going and coming years, the human heart, “yin” and “yang”, or the moon and the sun. The daidai, whose name means “generations”, is said to symbolize the continuation of a family from generation to generation.

Traditionally the kagami mochi was placed in various locations throughout the house. Nowadays it is usually placed in a household Shinto altar, or kamidana. It has also been placed in the tokonoma, a small decorated alcove in the main room of the home.

Contemporary kagami mochi are often pre-moulded into the shape of stacked discs and sold in plastic packages in the supermarket. A mikan or a plastic imitation daidai is often substituted for the original daidai.

Variations in the shape of kagami mochi are also seen. In some regions, three layered kagami mochi are also used. The three layered kagami mochi are placed on the butsudan or on the kamidana. There is also a variant decoration called an okudokazari placed in the centre of the kitchen or by the window which has three layers of mochi.

It is traditionally broken and eaten in a Shinto ritual called kagami biraki (mirror opening) on the second Saturday or Sunday of January. This is an important ritual in Japanese martial arts dojos. It was first adopted into Japanese martial arts when Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, adopted it in 1884, and since then the practice has spread to aikido, karate and jujutsu studios.

*************************************************

For more about New Year decorations, click here. For New Year customs in general, see here.

A Wikicommons picture of a gorgeously decorated kagami mochi such that the actual rice cakes are barely visible, defeating the purpose one might say

Congratulations John. A well deserved honour. Green Shinto provides a wealth of information that would otherwise be inaccessible, wonderful photos and much food for thought.

A well-deserved honor for the on-going excellent resources, photos and information. Happy New Year!

Many thanks for the feedback, and I’m grateful to have such a readership for a blog which I never thought would attract so much interest. Blessed indeed…

Don’t forget to chew..

Mochi killed 9 people last year who choked to death on it..

Ha, thanks… Since it’s the year of the sheep, I think there’ll be a lot of chewing. Incidentally, there’s been a question from a reader about why the Japanese celebrate the year of the sheep on January 1st, but the Chinese in February. The simple answer is that the Japanese followed the lunisolar Chinese calendar until the Meiji Restoration, after which in 1873 they changed to the Gregorian system. It brought confusion regarding the new dates for seasonal events, which means that even now Obon gets celebrated in some places in July but most places in August. Though the lunar calendar is honoured in some aspects still (good fortune days for instance, and certain festivals), but Westernisation has imprinted itself on the Japanese consciousness so strongly that it’s natural for contemporaries to think of the ‘new year’ as Jan. 1 now. Politically it’s also useful in distinguishing a ‘Western’ Japan from its Asian neighbour.

新年 明けまして おめでとうございます^^