As an animist religion, Shinto sees the spirit world as underpinning that of the physical. This is true too of the traditional swords, thought to have a spiritual presence. ‘The forging of a Japanese blade typically took weeks or even months and was considered a sacred art,’ says Wikipedia.

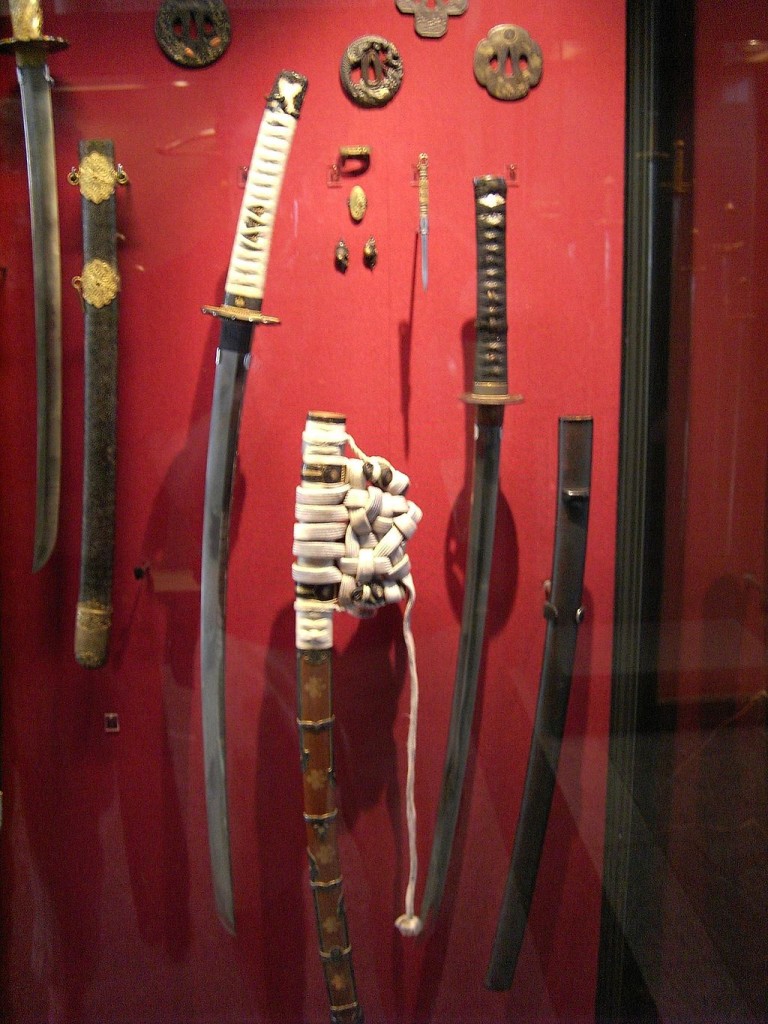

Traditional Japanese swords (courtesy Wikicommons)

Writing of the blacksmith in Bushido, The Soul of Japan, Inazo Nitobe commented, ‘Daily he commenced his craft with prayer and purification, or, as the phrase was, “he committed his soul and spirit into the forging and tempering of the steel.” Every swing of the sledge, every plunge into water, every friction on the grindstone, was a religious act of no slight import. Was it the spirit of the master or of his tutelary god that cast a formidable spell over our sword?’

Where did the religious reverence come from? Mircia Eliade was probably not the first to point out that metal as a gift of Mother Earth had a spiritual fascination for ancient humans. ‘The blacksmith and the shaman come from the same nest,’ runs an old Siberian proverb.

The extract below is taken from the magazine Sacred Hoop issue 86. In ‘The Spirit of the Blacksmith’ Nicholas Breeze Wood writes of the Mongolian-Buryat blacksmith spirit. Given the links of early Shinto with Siberian shamanism, the traditions of the Buryat Mongolians may help shed light on the special nature of the Japanese sword.

***************************************************

THE SACRED BLACKSMITH

In Hindu mythology, Tvastar, or Vishvakarma as he is sometimes known, is the blacksmith of the gods, whereas Vulcan (Hephaestus) holds that role in Greek and Roman mythology, using as he does a volcano as his forge. In ancient Irish mythology, the sacred smith is Goibhniu, and in Wales he is Gofannon. Both of these names mean blacksmith in their respective languages. In Anglo-Saxon Northern Europe, Wayland the Smith, who is known in Old Norse as Völundr, is the heroic blacksmith, who has many legends associated with him.

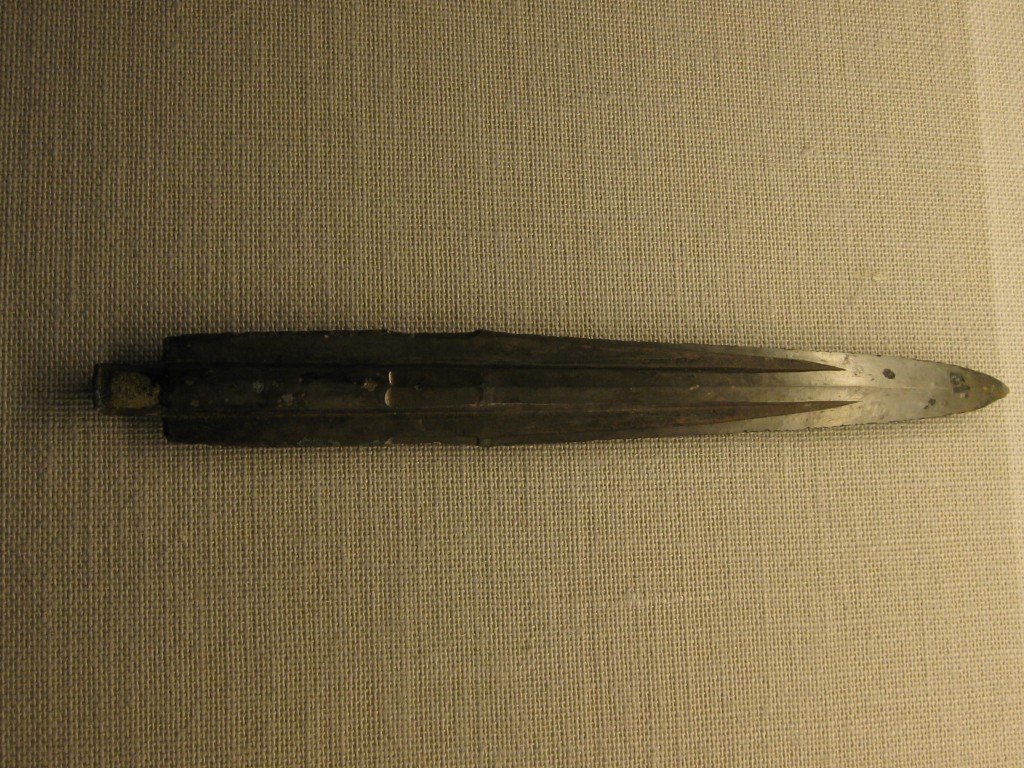

Yayoi sword (in Kokugakuin museum)

Traditionally in Siberia and Central Asia, the blacksmith is a very important person, closely related to the shaman; one Siberian saying is – ‘the shaman and the blacksmith are from the same nest’ – which sums it up well.

The blacksmith makes many of the shamans’ tools and pieces of equipment. He is the armourer of the shaman, and the iron objects fixed onto shamans’ coats or carried by them, are their armour and weapons. In Buryat tradition, such a smith and maker of shaman’s objects is called Dorligtoixun – ‘a person with Dorlig.’

According to Buryat legend, blacksmiths were taught by spirits from heaven called tengers, who were sent down to the earth to train human beings in the blacksmith’s art. They descended, carrying a hammer, tongs, and bellows ‘the size of a meadow’ to the peaks of mountains. The first people to be trained by the tengers handed down their skills to their descendents. Thus the role of smith became a hereditary one, generations of blacksmith families making the shamans’ ‘armour’, tools and weapons, being honoured for their work and their skill.

Iron was considered magical in its own right, but the smiths worked with other, non-ferrous, metals too. These smiths, like shamans, are divided into two groups: ‘white’ and ‘black.’ Blacksmiths generally forge articles from iron, the ‘black metal’, and their work includes domestic items, such as axes, knives and parts for horses’ harnesses, as well as shoeing horses. They also make the shamans’ items related to Damjin Dorlig such as metal parts for the shaman’s costumes, and iron parts for drums.

White smiths are those who tend to work with non-ferrous and precious metals, and their shamanic work would include making brass and bronze ritual mirrors, and the casting of amulets and bells.

Japan's imperial regalia, as described in the mythology

Thanks John, that’s really interesting. I wasn’t aware of the link between shamans and blacksmiths. Brian Cox featured a Japanese sword maker in the second episode of his current series ‘Human Universe’. It was fascinating to watch the process of the sword being made and the skill of the artist making it.

Thanks for that, Jann… I don’t know the series Human Universe, but certainly the spiritual nature of traditional sword making in Japan is very striking…

I’m glad I dropped in! You always have such inspiring articles.

I have a friend in Siberia, who happens to be a Shaman of the sacred Baikal island of Olkhon. In fact, I have a book he wrote in Russian, and gave me permission to translate. It has been so many years, however, I’m sure he has delegated the task to someone else in the mean time. I started a translation for the Kompira annual publication, but they were not interested, and I lost that work subsequently to a computer failure. (I took it as a divine order to desist.)

He said having a metal-worker in the family was one of the requirements to be a shaman.

I brought him a Shinto amulet once, a bell on a rope from Komitake Jinja on Mt. Fuji. He led me into his house to his kamidana, where he had the exact same amulet of the same size. The bells were of a different shape, but otherwise the amulets were identical. He also spoke with some amazement at receiving an arrow from Yasukuni Jinja, which had significance in Shamanism as well. The Buryat traditional dances at temples appeared to have similarities to shrine dances in northern Japan, such as the lion dances I’ve seen at shrines in Okutama.

I wanted to pursue this, but was subsequently denied visas.

Thank you for the input, Pat, and I share your interest in the similarities of Buryat shamanism and Shinto. The dance connection is intriguing – I hadn’t come across that. But what a great pity your project to translate the Russian book has never come to fruition. I for one would be fascinated to read it… I wonder if there’s any chance of the project being revived?

John, I owe a thanks to Claude for drawing my attention to your reply! I really should come visit your site at least weekly.

I will try to contact Valentin (I sent a message to a mutual friend) and either get permission again, or see about obtaining a copy if he has had the translation done by someone else. The title is “Shamanism I Mirovie Religii,” which translates as “Shamanism and World Religions.” I’ll run a search on that.

I just found this site, that mentions his book (but not a translation) and gives a good description of the author, Valentin Khagdaev. The book is apparently not available on the Net. I’ll do what I can to contact Valentin.

http://wings.buffalo.edu/ARD/cgi/showme.cgi?keycode=3146

And now Valentin has his own website here: http://valentinhagdaev.narod.ru/ in Russian. And I could contact him directly! Hopefully, we will get something going.

Thank you for the links, Pat. I tried to meet Valentin Khagdaev when I visited Baikal but he was away. There was virtually no information about him on the internet at that time (some eight years ago). Now I see that there are plenty of links about him, and quite a few Youtube videos about Siberian shamans too…

There are numerous kami related to Japanese Swords and swordsmithing.

It seems the most ancient kami of Metallurgy is Ame-no-Ma-Itotsu-no-Kami (Heavenly One Eyed Deity), related to other smith gods from other religions and cultures. Like Héphaïstos. According to Mircea Eliade, those gods often have one eye and / or one leg.

It is also known the most ancient iron weapons and tools came from meteoric iron.

For those archaic societies, smithing meant to harness the power of the Nature, star gods who fell from the skies. Iron was power. And still is. Probably, after creating the first iron sword, they started to look for other stars falling from the skies in the night, traveling and increasing their territory and their might.

Finnally, Ame-no-Ma-Hitotsu-no-Kami traveled to the most eastern region and couldn’t go further, he then stayed their, just as many other ancient gods, just like the hindu gods under the name of Hotoke, just like Buddhism. They stayed and endure the passing of time, the Terror of History. Shinkoku, not the land of the gods, more like the graveyard of the gods, where they fell asleep and slowly fade away.

Modern shintoists are wrong to not worship this ancient god who taught them blacksmithing.

Fascinating… Thank you for the input.