Green Shinto previously carried a review of last year’s Heldt translation of Kojiki by Quin Arbeitman. He noted that the new translation was “A much needed development, as the Basil Hall Chamberlain translation is generally considered a needlessly difficult read, and the well-regarded Philippi translation sells for hundreds of dollars due to the fact that reprints are prevented by legal squabblings over his estate.”

Green Shinto previously carried a review of last year’s Heldt translation of Kojiki by Quin Arbeitman. He noted that the new translation was “A much needed development, as the Basil Hall Chamberlain translation is generally considered a needlessly difficult read, and the well-regarded Philippi translation sells for hundreds of dollars due to the fact that reprints are prevented by legal squabblings over his estate.”

The Japan Times this weekend carried another review of Gustav Heldt’s translation by Stephen Mansfield, whose writings on Japan are to be commended. Mansfield praises the translation for its ‘beauty of language’, though his main concern lies in the way the mythology lends itself to nationalist feelings.

It’s pertinent to point out here that until the Edo period Kojiki was a little known work, considered more or less to be the family history of the imperial lineage. Only through the exhaustive work of Motoori Norinaga, a chauvinistic figure who hated China and upheld the superior qualities of the Japanese, did the book become more widely known.

In the review below, Mansfield considers the political usage that the Kojiki has been put to in the past. Indeed, since Meiji times the Kojiki has been upheld as Japan’s prime piece of mythology, though by all accounts it is the Nihongi, published eight years later in 720, that presents a more balanced and objective view. It is for that reason that Green Shinto hopes that Gustav Heldt, or someone like him, will do a similar job for Japan’s other great work of mythology.

********************************************************

The origin myth that beat the drums of war

BY STEPHEN MANSFIELD SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES FEB 28, 2015

Since the 18th-century — the age of English historian Edward Gibbon — Western theories of history have held that the past consists of causes, effects and events; there are no determining laws or theorems, and no divine purpose. This is the opposite of the view held by the classic Chinese historians, who saw history as preordained but manageable by decree; its purpose was to legitimize the current dynasty. The Kojiki is closer to this view of history — a past that can be used to validate the present.

Izanagi and Izanami, primal creators of Japan according to the 'Kojiki'

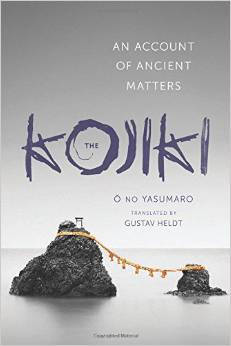

It is interesting to conjecture whether the earliest readers of the Kojiki, a complex work compiled in the Nara Period (710-794), understood the contents of this work as historical documentation or as a great hanging mirror — a surface of symbols and fictive events. Gustav Heldt, the latest scholar to translate this “account of ancient matters,” hopes it will grant the contemporary reader a broader understanding of the foundations of Japanese history, religion and literature.

Far from being a chronicle obscured by the blur of time, Heldt regards the Kojiki as a “monument to the human imagination, worthy of inclusion in the pantheon of world mythology,” finding in it parallels with sacred books such as Hesiod’s Theogony, the Hebrew Bible and the Popol Vuh. In his elegantly crafted introduction, Heldt establishes his credentials not merely as a translator, but a writer. This enabling gift is significant: It is what makes, for example, Junichiro Tanizaki’s modern rendering of The Tale of Genji so engaging as literature.

If you thought the casts of literary classics such as John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga or Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude were difficult to follow, the Kojiki will be an equally demanding read. Heldt’s decision to name practically all the locations, spirits and human figures in the narrative requires readers to stay on their toes. Many of these names, however, such as Moorland Elder, Flickering Flame and Root Splitter are distinctive enough to stick. And how could anyone forget the name Water Gushing Woman?

Susanoo slays the eight-headed monster, Orochi, part of the Izumo cycle of stories in Kojiki

The well-formed structure of the account helps in its negotiation: the first book focuses on the spirit world, the second on mortals and the third on complex succession issues. The clarity of the narrative improves considerably when figures from the Kojiki are linked to events, such the exploits of heroic warriors, or the journey of the mythological first emperor, Jimmu (who supposedly lived 711-585 B.C.), from Kyushu to the vale of Yamato. Or when the realm of spirits coexisting with legendary figures is superseded by the elemental and human. In a section of song, translated by Heldt as “Withered Moor / was burnt for salt / the charred remains / made into a zither,” we understand implicitly the transformative influence exerted by mortals over nature.

The first translation of the Kojiki into English was made by Basil Hall Chamberlain in 1882. When I asked Heldt if he felt any competitive pressure producing a fresh translation of the work, he expressed satisfaction at having created a more accessible version of the work, one that, unlike its predecessors, is defined by more textually nuanced content.

The co-opting of the Kojiki in the 1930s and ’40s as a text to validate — even sanctify — the political ideologies of the far right, was perhaps inevitable given that the Emperor was regarded as a god until as recently as the end of World War II. It is not surprising to find that in a 1940 film version of the Kojiki, Japan’s mythological Sun Goddess, Amaterasu Omikami, is seen benignly casting the light of civilization over Asia, or at least the nations under the heel of Japan’s imperium.

Butoh rendition of Ame no Uzume, whose provocative dance lures Amaterasu out of her cave

My review copy of this book turned up a few days before Kenkoku Kinen no Hi (Foundation Day), a national holiday that suggests the Japanese still take their creation myths seriously; not perhaps literally, but as a component of their national heritage. When asked what he considered to be the relevance of these ancient accounts today, Heldt highlights the ongoing reappropriation of its characters and stories in forms of popular culture that are now spread across the world.

Of particular interest was his remark concerning the relevance of the myths in the Kojiki to a resurgent Japanese nationalism. Heldt cited the name Izumo, which is used for the country’s first helicopter carrier warship constructed for the Maritime Self-Defense Force. According to Heldt, this associates the helicopter carrier with the WWII battleship Yamato — Izumo and Yamato being major rivals in the Kojiki. As Heldt puts it, “Izumo’s mythical, cultural and historical ties with the eastern coast of the Korean Peninsula also signal Japan’s growing concern over its maritime border with the continent.”

Ultimately, mythology is what might be termed pure fiction, or original literature. Like faith, it requires an immense suspension of disbelief if the reader is to plunge into the narrative and be buoyed along unimpeded by doubts — the skepticism associated with the rational, inquiring mind. For the reader willing to surrender his or her empirical insistencies — to luxuriate in the beauty of language — the Kojiki is time well spent.

Okuninushi, lord of Izumo, who according to the Kojiki was forced out by the Yamato lineage and became master of the underworld. It's said that Izumo Shrine stands on the site of his palace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_fVADGrSdg

If a country’s population don’t study it’s myths, it will fall apart, because they will loose sense of national identity.

As for me, I believe the Eternal Return is true. And I also believe “天” exist (because 天 is way to subtle to not exist, it’s completely different than proving God don’t exist).

And I also think divine purpose can’t be proven wrong, because even the Monotheist God there is no proof he does not exist, even if we admit Maimonides was right (and thus that the Creationist dudes are wrong).