Entering into another world

This is part of an ongoing series about the Shinto way of death, adapted with permission from an academic article by Elizabeth Kenney. It shows how traditional Shinto arrangements differ from those of the Buddhist funeral. Though the research was carried out in the 1990s and some of the information is dated, the fundamentals still apply. For the original article, see Elizabeth Kenney ‘Shinto mortuary rites in contemporary Japan.’

Conclusion

The Shinto funerals of today’s Japan are part of a crowded religious landscape unimaginable to the Edo Shintôists who first created funeral Shinto. Buddhist funerals are the norm, and most Japanese people find comfort in the familiarity of Buddhist rites. But the dominant position of Buddhism in the funeral establishment inevitably inspires opposition in a few Japanese.

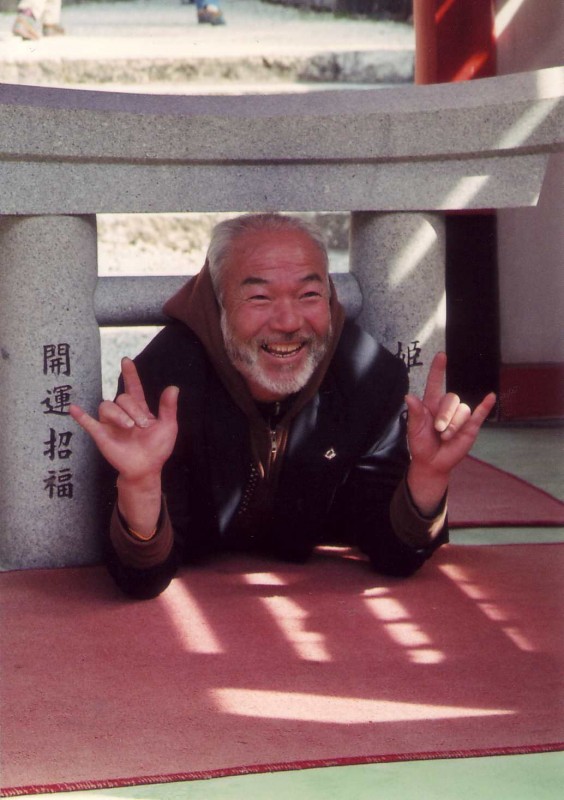

Buddhist graveyard with Shinto torii

Some of these people want to create a unique funeral that expresses their own vision of life and death. A few others are no-nonsense consumers who want to save money. But for most people who have a Shinto funeral it expresses their religious, cultural or family identity more than anything else.

(After all, there is no need to turn to Shinto if one is primarily seeking to avoid Buddhism. “Non-religious” funerals are socially acceptable and increasingly common. They tend to be solemn affairs, with a director of ceremonies instead of a priest. Incense-offering may still be a part of these non-religious funerals.)

As this article has outlined, Shinto mortuary rites follow the course set by Buddhism: 1. preparation of the corpse; 2. wake; 3. funeral; 4. procession; 5. cremation or burial; 6. grave; 7. posthumous name and memorial tablet; 8. memorial rites.

All the same, it is important to remember that many of these funeral practices are not inherently Buddhist but Japanese: giving a last sip of water; washing and laying out the corpse; covering the kamidana; offering food; purification after the funeral; the mourning taboos; ancestor worship. In fact, the Buddhist funeral dictionary classifies all the activities just listed as “traditional customs”, not as Buddhist rites.

To the Buddhist (or popular religious) elements, the Shinto funerals add one remarkable rite: the transfer of the spirit of the deceased from the body to the memorial tablet. In other parts of the funeral process, Shinto actions or objects are substituted for Buddhist ones.

Through a series of functional substitutes (of which tamagushi for incense is the most noticeable), a set of distinct Shinto meanings is established. The ritual is in place, available to Shinto priests willing to perform it and lay people wanting it. Ritual questions are answered, but (and not only to the outsider’s eye) other sorts of questions — about impurity, the afterlife, and more — remain open to individual resolution.

The tamagushi offering remains a distinctive mark of Shinto

Leave a Reply