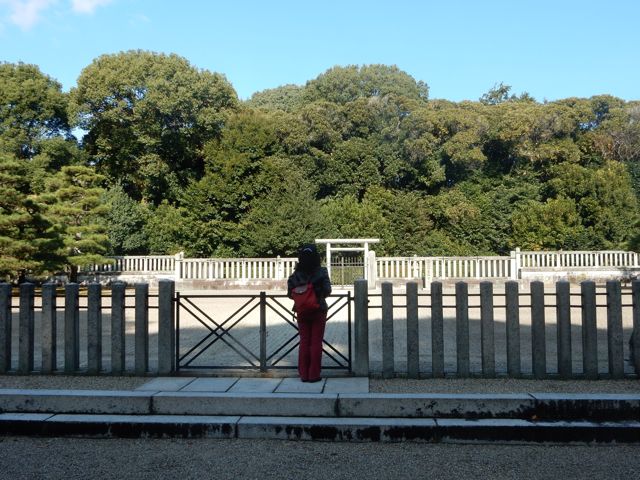

The modest entrance to the burial mound of Kyoto’s founder, Emperor Kammu. In the background is Hideyoshi’s Momoyama castle (rebuilt in modern times in concrete).

In the south-east corner of Kyoto, between the railways stations of Tambabashi and Fushimi Momoyama, is a peaceful wooded area containing the burial mounds of the first and last emperors to reside in Kyoto. In less than an hour, you can traverse over 1000 years of history. There are historical associations and untouched nature, yet few people visit this parkland despite its proximity to the famous Fushimi saké area.

The Hailstones Haiku Group recently did an outing to the area, starting with the burial place of Emperor Kanmu, a mere fifteen minute walk from Tambabashi station. Only the occasional jogger passes by to pay respects, but personally I find it an awe-inspiring site. Firstly, as the founder of one of the world’s great cities Kanmu surely deserves the gratitude of those who have inherited the benefits of his visionary act in 794.

The city that Kammu founded in 794

Here is the man who pretended to set out on a hunting expedition while scouting for a new location for his capital just ten years after relocating from Nara to Nagaoka-kyo. Latest research suggests the site was prone to flooding, and so he determined to move again.

According to tradition, from the vantage point of Shogunzuka he looked out with Wake no Kiyomaro over the river basin of Kyoto and saw that geomantically it was perfect – mountains on three sides, a body of water to the south (Lake Ogura), rivers to east and west, and mighty Mt Hiei guarding the Devil’s Gate in the north-east.

A second reason for awe is that his grave, like others of its ilk, typifies the blending of ancestral worship and animism that form the twin pillars of Shinto. In the planting of the corpse into the earth, and in the nourishing of the plantation that grows above it, is an interlinking of human and nature made manifest in the lush evergreen growth. In this way the deceased evolves into the landscape, and the trees that reach up to heaven are imbued with human essence. The posthumous spirit is thus transformed into a true spirit of place. Ancestral and animist are one and the same.

Sunlight spotlight

Kammu’s final resting place –

Ripe, ripe persimmon

Autumn leaves

Scattered in a wreath –

Kammu’s mound

A twenty minute walk through pleasant woodland brings one to the much more substantial grave of Emperor Meiji. Here is evident the pomp and glory of State Shinto, as the Restored Emperor at the centre of the Meiji regime was given a full-scale burial designed to impress. You only have to stand at the bottom of the huge stairway leading up to the shrine to realise the grandeur by contrast with that of Kammu.

Stairway to heaven – the steps up to the burial mound of Emperor Meiji

Meiji was born as plain Mutsuhito in Gosho (Former Imperial Palace), and a plaque there marks the site of his Parturition Hut. (Birth being considered a form of pollution was traditionally done outside the palace proper.) He was the last emperor to be born in the city, and the last who could be considered a Kyoto man. His father died when he was 14, making him emperor, he was ‘restored to power’ at the age of 15, shifted the capital to Tokyo and married at 16. Quite a start to life by anyone’s standards!!

Previous emperors in the Edo Period had been buried at the Shingon temple of Sennyu-ji in south-east Kyoto, and the imperial cemetery there is known as Tsukinowa. Meiji was something of a poet, and after paying respects at the grave of his father, Emperor Komei, he penned the following:

When I visited

The tombs at Tsukinowa

On my sleeves

Old needles from pines

Kept falling

Like Victoria, Meiji reigned over an age of astonishing changes – in industry, commerce, social composition, politics, foreign relations and military standing. Small wonder that so many clung to him as the one unifying factor in such turbulent times.

On the evening of Sept 13, 1912, a cart decorated in gold leaf and lacquer, drawn by a team of oxen, left the Imperial Palace in Tokyo with a procession of people carrying banners, torches and ceremonial arms. The coffin was loaded onto a train, which left in the cover of dark for the emperor’s state funeral and final resting place. He had apparently asked specifically to be buried on the green hills that he remembered visiting from his childhood. The place was known as Kojosan (Old Castle Hill) because it was the site of Hideyoshi’s Momoyama Castle. Now it’s known as Momoyama Goryo (Burial Mound).

Emperor’s mound –

The sound of birdsong

Like gagaku

Out of view, and discretely located to one side, is the burial mound of Meiji’s chief wife, Empress Shoken who died two years later. She had no children of her own, whereas her husband had fifteen by his concubines, or official mistresses. Unlike Jewishness, it’s the male line that counts in Japaneseness, and so she adopted the son of one of the other ‘wives’ and brought him up as heir apparent (later to become Emperor Taisho).

Dead pine

At Shoken’s grave –

Ever green oaks

Not far away from the imperial mounds, just ten minutes walk, is the shrine of Meiji’s most devoted servant, General Nogi, who served as governor of Taiwan.

Nogi was the last person (together with his wife) to commit junshi, ritual suicide to follow one’s master into death. He first came to prominence in the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 (known to filmgoers for the final battle in The Last Samurai). In charge of the emperor’s banner, he was horrified when it was seized from him and he suicidally plunged into the enemy ranks to win it back until ordered to desist.

Count Maresuke Nogi (1864-1912), known in Japan as Nogi taisho (General Nogi)

After distinguished service against the Chinese in 1894, he was made commander of the forces who took Port Arthur from the Russians a decade later, thus helping cement victory against the Europeans in the 1904-5 war. He was appalled however at the loss of life of those under him and sent a letter to the Emperor requesting permission to commit suicide. Though the request was refused, he was apparently mindful of this when he and his wife took their lives in 1912 immediately following the funeral of Emperor Meiji. Some praised him highly for epitomising Japanese values of loyalty and devotion; others saw it as a retrograde act of feudalism in a modernising age.

There are five Nogi shrines altogether, with the main one in Tokyo at the place of his suicide. The Kyoto shrine was built in 1916, and because of the general’s love of horses there are a pair in front of the Worship Hall overshadowing the komainu guardians. There’s also a small museum of his life and a scene of his humble upbringing in Edo, as pictured below.

Last blue butterfly

fluttering behind grass –

thoughts of times gone by

That’s a cool story, been at that shrine and wondered what it was all about

Thanks. I hope to get up a special posting about Nogi Jinja. It’s a curious place and full of interest.

Thanks for the post and the poems John. Very fitting for a haiku walking tour. The shrines you visited and wrote have about opened up a new aspect of Japanese history for me. I look forward to reading more about it.

Thank you for the input. I strongly recommend the area when you are visiting Kyoto, if you are in need of a quiet retreat from the crowds at more famous tourist places. It is one of those fringe places in Kyoto, close to nature, which make living in the city such a blessing.