The mighty sanmon gate at Tofuku-ji, largest and oldest Zen gate in the whole of Japan

Look at the picture above. It shows the classic arrangement of structures in a Zen monastery, with lotus pond, ceremonial gate and Teaching Hall (Hatto) perfectly aligned on a central axis which runs from south to north. Through the middle of the three openings in the gate is framed the main altar area, inside which a statue of Shaka Nyorai (the historical Buddha) is flanked by two attendants and fronted by four guardians.

It’s all very imposing, very symmetrical and very Chinese. The floors are stone and you keep your shoes on. The deities are represented in physical form. The ideology is conceptual and predicated on an afterlife. It’s all very, very alien to Shinto. And yet, surprise, surprise, to the right of this ceremonial gate is a Shinto shrine, guardian of the spirit of place. In fact the shrine predates the temple, which incorporated it into its design and for some eight hundred years has preserved and cherished it. Does Zen cultivate belief in kami?

In his book about Zen and Japanese Culture, D.T. Suzuki claimed that Zen lay at its core and ascribed to it many well-known aspects such as archery and the tea ceremony. Yet it seems to me that if Zen shaped Japanese culture to some extent, it’s also the case that Shinto shaped Zen to a certain extent. The imported religion derived from Chinese Chan Buddhism, but after its arrival in Japan it took on practices and forms not found in the country of origin.

For the next few months I’ll be investigating the development of Zen in Kyoto, and while doing so I’ll be looking out for the influence of Shinto and the role it’s played in the religion. One interesting item to note is that the Shinto shrines housed in Zen temples usually date from two distinct periods. One, such as here at Tofuku-ji, is from a time before Zen was introduced to Japan in the late twelfth century.

Other shrines were added after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Shinto was made the state religion and Buddhism fell into disfavour (over 20,000 temples were destroyed). Many temples erected shrines at this time to appease the authorities who considered Buddhism a threat to the emperor-centred regime. (The religion had been a mainstay of the Tokugawa shogunate, for every citizen was required by law to register with their local temple – even Shinto priests!)

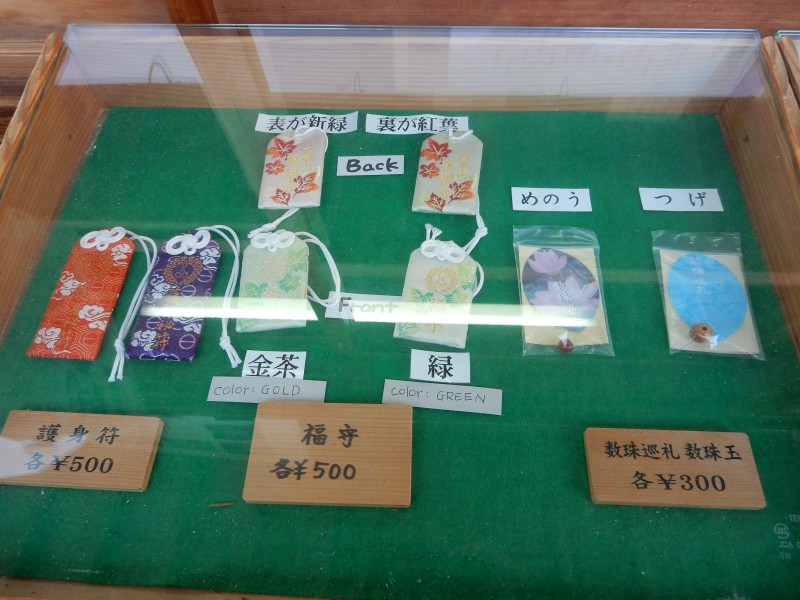

As well as temizuya (water basins for purification), Zen temples sell ‘omamori’ protection amulets. Like the traditional Shinto amulets, these are for protection and happiness. There’s a single bead too, part of a rosary which is put together by visiting different temples.

A Zen altar in a subtemple at Tofuku-ji in Kyoto. What has that got to do with Shinto? Well, the New Year offering seen in the picture is a ‘kagami mochi’ usually associated with Shinto and placed on the kamidana. No one is quite sure of the origin, but one theory has to do with honouring the rice spirit. The mirror of course is sacred to Amaterasu as a symbol of her spirit, but the mirror too is commonly found in Buddhist temples as a reminder to keep the soul spotless and free of dust.

The Gosha Jokyuju (aka Gosha Myojinsha) shrine was erected by a powerful member of the Fujiwara family, Tadehira, in 925. It incorporates five tutelary shrines of Tofukuji (Iwashimizu Hachiman, Inari, Kamo, Kasuga and Hiyoshi). Its festival, known as Shoshasai, was once as brilliant as the Gion Festival but is defunct. Now an annual Fire Burning Festival called Hitakisai is held in Nov.

The shrine houses a curiously coloured rock, presumably the ‘goshintai’ (sacred body) of the rough bear spirit, Arakuma. It was donated by the Mizuguchi Organisation of Fukuoka Prefecture

A pair of dosoujin. These fertility symbols would once have acted as territorial markers, but now they rest beneath a tree, evidently cared for still by the Zen monks.

The dry landscape garden by Shigemori Mirei was laid out in 1939 and is acclaimed for combining modern style with traditional sensibility. The rocks here represent the Isles of the Immortals from Chinese mythology, but the simplicity, purity and spiritually charged rocks may well owe something to the native tradition.

I’ve noted a number of Shinto features appear related to chinese folk religion (Iconigraphy of Sarutohikonomikoto and Guan Yu, for example) and Folk Taoism. Taoism clearly shaped Chan in many ways. And then was shaped by Chan in turn. Its all an exciting and potent mix.

Thank you for the input, and you’re right to point to the decisive influence of Taoism. It was formative on both Zen and Shinto, so it would be surprising if there were not elements in common between them. The suspicion of language and rationalisation is one key aspect, for instance. ‘He who knows does not speak… ‘ So I will say no more!

I’m really looking forward to your future articles on this subject. I have often wondered if the native Shinto traditions and concepts predisposed the Japanese to the influence the Chan Buddhism and when it was imported from the continent.

Thanks for the thought. I’m not sure if it predisposed Japanese to accept Chan Buddhism… after all, other forms of Buddhism had already taken root and prepared the way. But perhaps there was something in the native tradition that harmonised with the ideas of Chan Buddhism… It’s certainly worth considering.

Likewise, I’m looking forward to your future articles on this subject. Your first instalment has already enlightened me. Strange as it may seem, I have found Zen one of the trickier types of Buddhism to get a handle on, particularly as it relates to the elements (earth, air, fire, water and ether/void). So far I have not been able to find as direct links as, say, in Shingon Buddhism. I will be delving deeper into these connections in the coming months. Any pointers would be appreciated. :-)

I think, Jann, with the amount of material you’ve amassed about the use of elements in Japanese culture that it’s you who will be teaching me one or two things!

Nice of you to say so John. We can do a tally at the end of my time in Kyoto!