The entrance gateway to the Founder’s Hall (Kaisando) at Kennin-ji, where Myoan Eisai is buried

My second outing into the world of Zen was a visit to Kennin-ji, oldest Zen temple in Kyoto. It’s located in the heart of Gion, the city’s largest geisha district. As a result it is neighbour to the pleasure quarter with its drinking bars and love hotels. Tourists focus their cameras on the geisha, unaware that within feet are temple treasures and gardens of outstanding beauty.

The mix of worldly and otherworldly pursuits is characteristic of Japanese religion, meaning that the temple teahouses with their spartan furnishings stand alongside geisha teahouses where customers are plied with drinks and flirtation. The ‘floating world’ of Buddhism here merges with that of ‘the water trade‘, and, as the wits have it, paradise can be found on both sides of the temple wall.

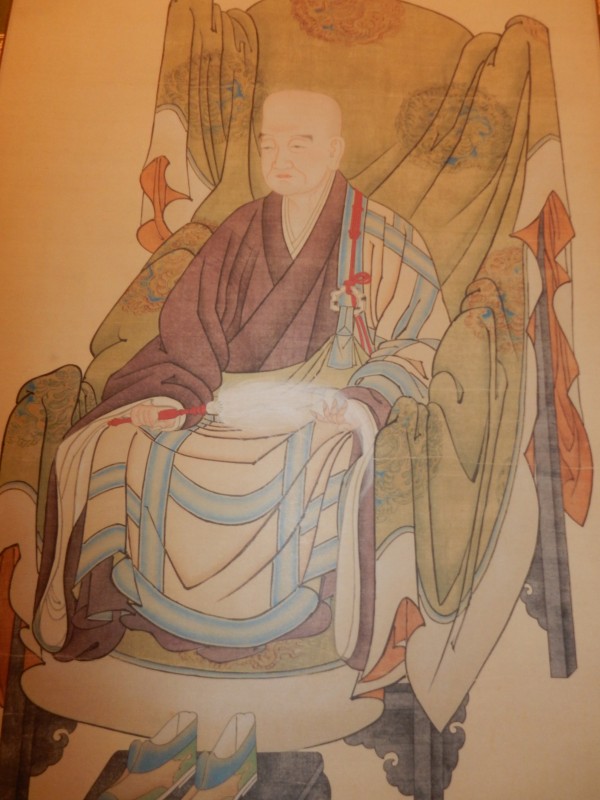

Myoan Eisai (1141-1215)

Interestingly, the temple’s founder, Myoan Eisai (1141-1215), was the son of a priest at Kibitsu Jinja in Okayama. Brought up in a Shinto household, he was sent away to study Buddhism at the tender age of three and was later ordained into the Tendai sect on Mt Hiei. As the man who introduced Zen to Japan, it’s surely not without significance that Eisai’s upbringing was shaped by the native tradition and Shinto values. (It was an age when Shinto and Buddhism were seen as complementary and fused into one; Eisai’s contemporary, Kamo no Chomei, writer of Hojoki (1212), dropped out of being a priest at Shimogamo Jinja to become a Buddhist hermit.)

After visiting Kamakura and securing patronage of the shogun, Eisai established Kennin-ji as his base. Although he taught and practised Zen, he remained a Tendai priest to the end of his life. Tendai was a very pragmatic sect and its founder Saicho had encouraged worship of the native kami, particularly Sanno, mountain spirit of Hiei where the head temple of Enryaku-ji stood. The sect had close ties with tutelary guardians and protective shrines (chinju). In the case of Enryaku-ji, it was Hiyoshi Jinja at the foot of the mountain. Eisai carried on the tradition, and the guardian shrine of Kennin-ji was the nearby Ebisu Jinja.

Myojouden, the small Shinto shrine in the eastern part of the temple precincts honouring Raku Daimyojin

Eisai preached that Zen aims to diminish the ego and that it promotes purity, sincerity and unselfishness. It was therefore good for the country and for a harmonious, peaceful society. This is remarkably close to Shinto teaching when you think about it. Rather than the individual ego, Shinto is community oriented and encourages suppression of self for the greater good. For the sake of harmony, selfish impulses should be nullified.

Eisai lies buried in the Founder’s Hall of Kennin-ji, and close to the hall stands a small Shinto shrine, Myoujouden. Legend has it that when Eisai’s mother went to worship at Kibitsu, she had a vision of a bright star and subsequently became pregnant (sound vaguely familiar?). The child turned out to be Eisai, marking him out as special. The kami associated with her vision was Raku Daimyojin, which in syncretic terms equated to the boddhisattva Kokozo Bosatsu, a guardian of learning and knowledge. Consequently the small shrine tends to be popular at exam time with students.

Shrine offerings were well maintained and kept free of birds

Shrine building, housing the spirit of Raku Daimyojin

Once a year there’s a ritual carried out here conducted by one of the Zen monks. Such shrines and activities are not included in the official figures as ‘Shinto’. In other words, there are literally many thousands of temple shrines throughout Japan that are overlooked when people give numbers for ‘shrines’. My feeling is that such syncretic shrines should definitely be included and that the official statistics should be disputed. The true religion of Japan is not neatly divided into Shinto and Buddhism, as people pretend.

Wild boar at the Marishiten Hall with lots of little boar ‘omikuji’

The small Shinto shrine lies on the eastern side of the Zen temple’s grounds. Over in the south-west is a much bigger and thriving complex within the Zenkyo-an subtemple. This is the Marishitendo (Marishiten Hall), dedicated to an imported Indian goddess (originally Marici). Like Japan’s kami, Marishi Sonten was a guardian deity of Hindu/Buddhism who was adopted by practitioners in China. A priest who had made a small statue of her in clay brought it with him as protection in 1327 when he travelled to Kennin-ji as a teacher.

According to the Zen priest I talked to, Marishiten is Queen of Heaven, a particularly powerful deity with a radiance that dazzles those who look upon her like the sun. Consequently she was popular with warriors, who sometimes carried a statue of her in their helmet in order to dazzle the enemy. According to the priest, so powerful was the goddess that she overcame Kennin-ji’s previous spirit of place and took over its role as guardian of Kennin-ji.

Marishiten is known for bringing luck to devotees, and geisha come to make prayers to her. The subtemple is covered in images of wild boar, which is her messenger, and she is depicted as riding on a set of seven golden boars (in India the animals are known for their wiliness as well as their bravery). Japan has three main Marishiten temples – a Nichiren temple in Tokyo and a Shingon temple in Kanazawa in addition to Kennin-ji.

As I talked to the Zen priest in his shop with Marishi-related goods, there was a steady trickle of visitors and people praying at the shrine. Zen has an austere, atheistic image in the West. Here at the shrine of Marishi Sonten in the corner of Kennin-ji, the atmosphere was altogether different. I had a strong feeling that such deities offered a personal means of connection for the worshippers that ‘just sitting’ and looking inwards may not.

Raijin, the thunder god, is surrounded by drums on which he bangs. Fujin (wind god) has a billowing scarf full of air as he speeds along below his companion.

The temple is famous for paintings by Tawaraya Sotatsu of Raijin (thunder deity) and Fujin (wind deity) – personifications of unseen forces.

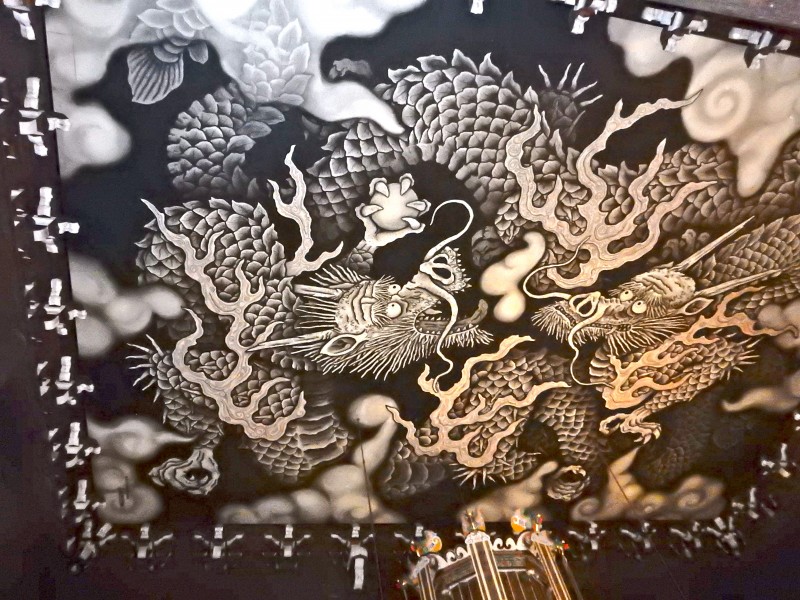

Another of the temple’s most prized items is an early twenty-first century painting of twin dragons on the ceiling of the Lecture Hall (Hatto). Most temples have one dragon, but here there are two in the A-Un pose of temple and shrine guardians (one with mouth open, one with mouth shut to symbolise Aum – Om). Shinto too adopted the Chinese dragon as a guardian figure, not only in the form of the deity Ryujin but as a popular motif for spouts at shrine water-basins.

Omikuji fortune slips, surely borrowed from the native tradition, here in the form of monkeys or tigers (Bishamonten’s familiar)

As at Shinto shrines, good luck charms or protective amulets are also sold at the temple (these are for victory). Did the practice come with Buddhism, or was it already part of the native shamanic tradition?

Well written, interesting history too

Thanks, Hugo… The temple is often overlooked because of its drab appearance compared to some of the grander monasteries, but I found it most appealing and the artwork is stunning…

Thank you so much for your blog! I just came across your site while researching Hata clan while reading Shinto Shrines book (which you also co-authored!) We are travelling to Kyoto in

January and are thrilled to have found such a rich and well-researched cultural and historical info here.

Thank you for writing in… It means a lot to get such feedback and encourages me to keep on posting.