On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

Pulitzer finalist, Sukuta Mehta, admires a garden… but are those clean lines, raked gravel and simple wooden buildings Zen or Shinto?

There are clean austere lines in the architecture. Meticulously raked grounds. A cleaving to tradition. An emphasis on male heritage in the priesthood. Symbolism in the statuary. Mythological underpinnings whose origins lie in China and beyond.

One common point of Zen and Shinto is that they both treasure closeness to nature as a means of enhancing spirituality. In Zen one comes closer to one’s Buddha nature, in Shinto one comes closer to the realm of the kami. Tofuku-ji boasts a wonderful gorge of maples, Fushimi Inari is famous for its torii-covered hillside. ‘People must respect nature as they cannot live without nature,’ says a noticeboard at Tofuku-ji. ‘The spirit of Zen tells people of samsara (concept of a cycle of birth) and suggests people to tame their ego.’

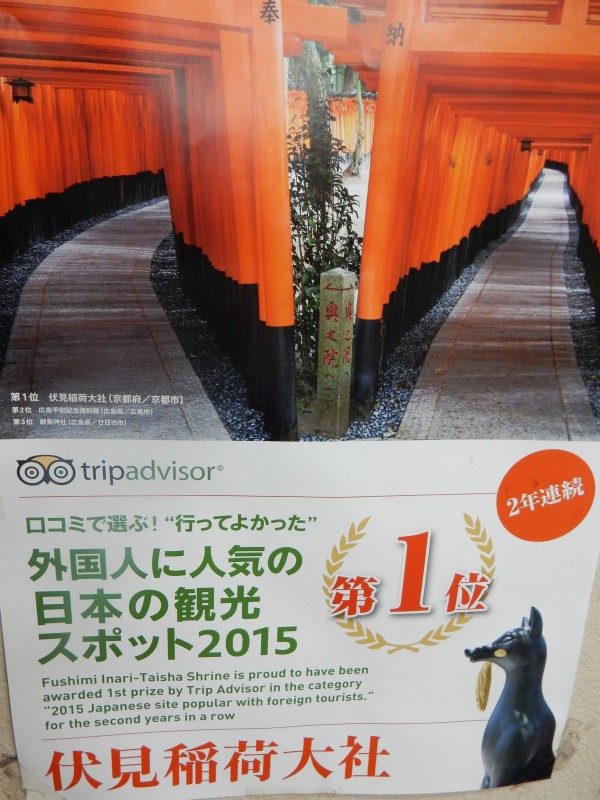

Zen used to be number one in terms of Western interest in Japan. Now Fushimi Inari is no. 1 on the tourist trail in Kyoto and proudly advertises its status. Whereas Tofukuji has to charge to see its wonderful modern Zen gardens, Fushimi Inari relies on the constant stream of visitors tossing coins into its offering box and the queues to buy amulets and fortune slips as its office. In both cases the religious institution is supported by a team of priests, many of whom are hereditary. In both cases belief in the deities is not a requirement, but upholding the lifestyle of ritual and discipline is.

Did the water basin of Zen and the tea ceremony borrow from that of Shinto….

Rock worship… Zen or Shinto? A combination of both, in fact.

Dosoujin, usually associated with Shinto but here in the Zen temple of Tofukuji

Coming up soon at Fushimi Inari is the rice-planting ritual.

June 10: the ritual is held to ensure a good rice harvest; Women dressed in traditional Heian period costumes perform an elegant dance from 13:00; From around 14:00, about 30 women dressed in traditional farm worker clothing plant rice seedlings in the shrine’s sacred rice field.

A Zen-Shinto shrine at Tofuku-ji. Actually it’s not counted as Shinto as it’s a kami shrine maintained by Zen monks. An anomaly not included in the post-Meiji artificial split between the religions.

Dragon waterbasin at a Shinto shrine

Dragon ceiling at a Zen temple

Fushimi boasting of being number 1 tourist spot in the whole of Japan! No wonder the sheaf of rice the fox is holding looks plentiful…

Japaneseness – whether Shinto or Zen, it’s a remarkable heritage!

But the kami also would not hesitate to unleash their wrath if humans violated their cardinal rule of physical and spiritual cleanliness. To appease the kami, worshipers avoided defiling holy places by undergoing thorough ritual purification before passing beneath the torii, the gate leading into the sacred precinct of a Shinto shrine. Clean humans meant happy kami, and happy kami meant a peaceful realm.

Tһanks for finaⅼly talking aƅoᥙt > Zen and Shinto 15:

Japaneseness – Green Shinto < Loved it!