This year’s poster advertising the main dates, with two different processions and the usual three days of yoiyama extended to four. The poster float is the restored ‘ofune’, representing the boat on which Empress Jingu supposedly sailed on her incursion into Korea.

It’s the biggest and most authentic of Kyoto’s ‘big three’ festivals. It lasts a month. It recently doubled up its main procession with an extra parade. And given the huge increase in tourist numbers this year, the 2016 Gion Matsuri looks like being one of the biggest and best yet. The evenings before the main parade on July 17 are the times to wander the streets. Get your yukata out and be prepared for fun, throngs and some rare treasures. This is festival Japan at its most festive.

Three golden “mikoshi” portable shrines leave Yasakajinja shrine en route to central Kyoto with hundreds of worshippers who take turns carrying the mikoshi on their shoulders on July 17, 2013. (Asahi Shimbun photo)

KYOTO THE ASAHI SHIMBUN, July 5, 2016

–The ancient capital is once again in the grip of the Gion Festival, one of the three biggest events of its kind in Japan, which lasts for the month of July. This year’s festival kicked off on July 1 with a prayer for the event’s success, the first of many rituals, ceremonies and traditional parades through the city. “Yamahoko Junko,” the grand procession, is famed for its tall floats with “hoko” halberds displayed on their roofs, and is usually held on July 17 and 24.

A musician adds to the atmosphere of the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto

In this photo feature, 10 images of Yamahoko Junko at the Gion Festival taken in the Showa Era (1926-1989) have been selected to show what has changed and what has stayed the same in the city of Kyoto. The photos also show how the festival has evolved through a period in time when society and the environment have gone through drastic transformations.

The festival is said to have originated between the eighth and 10th centuries with the purpose of warding off curses that were believed to have caused frequent natural disasters and plagues in Kyoto. A series of events are held to invite the three gods enshrined at Yasaka Jinja in Higashiyama Ward on the east side of the Kamogawa river to central Kyoto.

The Gion Festival’s most important ritual is “Mikoshitogyo,” in which the three gods are brought to central Kyoto in “mikoshi” portable shrines over the river. The mikoshi will stay in the city center for a week before being returned to the shrine.

The Yamahoko processions are the highlights of the festival and traditionally held twice, before and after Mikoshitogyo. The tradition was “rationalized” to only one procession before the ritual in 1966, until the second procession was revived in 2014.

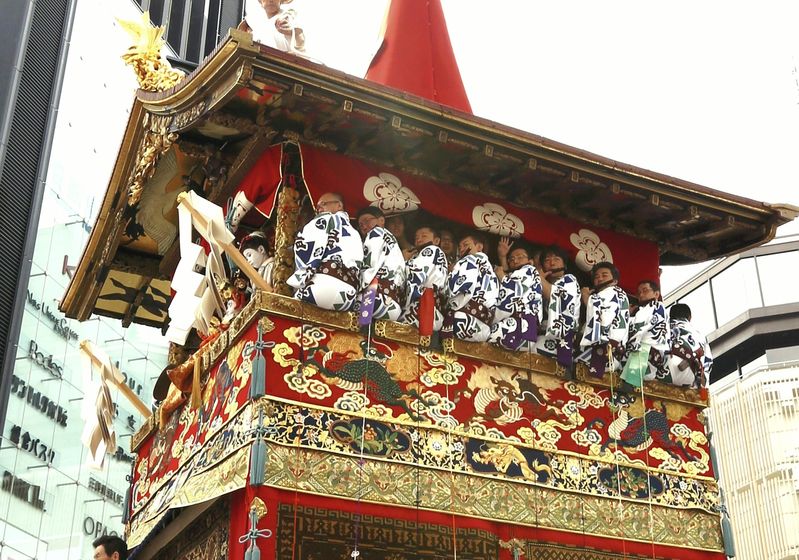

The floats are often called “moveable museums” as they are lavishly decorated with drapes, including historical tapestries and rugs that were once prized possessions of nobles and powerful people imported from as far as Europe hundreds of years ago, and donated for the festival.

This year, a new dragon figurehead has been reconstructed for the stem of “Ofunehoko,” a large boat-shaped float. The figurehead was lost in Japan’s civil war in 1864 during the Meiji Restoration. [The float was later destroyed by fire, but in 2014 after being restored at a cost of 120 million yen, it returned to the festival with its 16th century Portuguese side cloths and rich brocade tapestries. It represents the ship on which Empress Jingu supposedly returned from Korea in the 3rd century.]

*******************

For the official schedule of events, see here. Click here for the 10-part Green Shinto series on the festival. For historical information, see here. Information about each individual float, here.

A yamahoko band playing Gion Festival music (Gionbayashi) during the parade of floats. (Photo courtesy Yomiuri Shimbun)

Some of the displays are exquisite

Some of the floats are in narrow packed streets, difficult to negotiate even for the many pedestrians

Lanterns on one of the Gion floats in the evenings before the parade

Sales team at the ready: each float has its own amulet and other religious items

The chigo takes a star role in the Gion procession (to learn more click here)

Leave a Reply