courtesy Houki Town website

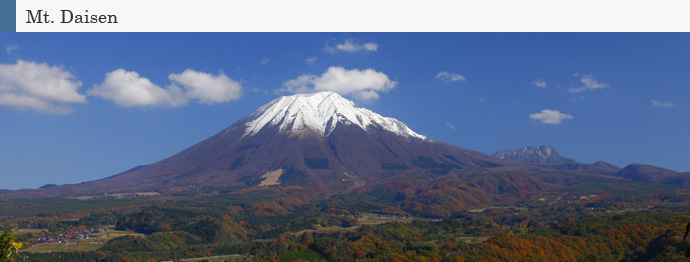

At 1,729 meters, Daisen rises as the tallest mountain in western Japan. It’s in Tottori Prefecture, on the way to the Izumo province of ancient myth. In the winter, the area transforms into the Okudaisen ski resort, drawing ski fans from all over the country with its views of the Sea of Japan and the Shimane peninsula. Locals like to call it the Tottori version of Mount Fuji thanks to its perfectly conical shape when viewed from the south side. From the west, however, it’s all craggy rough-hewn peaks. In the article below, the mountain’s religious history is covered, including its Shugendo connections. For those interested in ‘spiritual tourism’ off the beaten track, this is a most attractive option.

Fiery nights on Mount Daisen

By Rebecca Quin

I feel the heat before I see it as we wind our way in the dark along the stone paved approach up the mountain towards the shrine. A horn sounds and the orange glow of fire through the dark trees gets stronger. Turning the corner, I’m half expecting to see a legion of armoured samurai readying for battle – what’s waiting on the steps to the summit is less terrifying but just as impressive. It’s the opening of the climbing season on Mount Daisen, known as “Okami-no-take” or “the mountain of the gods”, where climbers come to take part in an ancient festival to ask for safety and protection among its volcanic peaks – the highest in the Chugoku region. The festival is one of the area’s most popular, attracting more than 2,000 people over the first weekend of June.

The main event is a “Game of Thrones”-style torchlight parade down from the misty mountaintop guided by fur-clad “yamabushi” (warrior mountain priests) and the long, deep echo of their conch shells. This year, the invisible, steady patter of rain joins us.

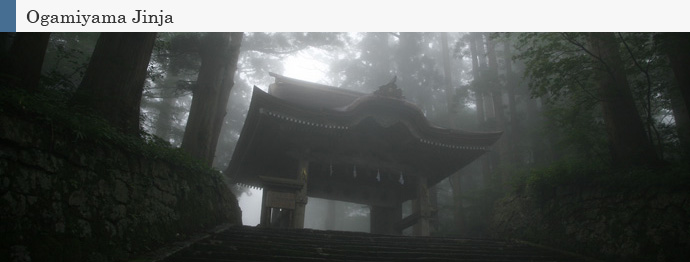

The Shrine for the Mountain of the Great Spirit ‘Ogamiyama’ (from Houki Town website)

Crowds in brightly-colored rain jackets were jostling for shelter under the gray eaves of Ogamiyama Shrine where the parade began. We’d visited the shrine earlier that day and I spot the two “komainu” or lion-dog statues still guarding the stone steps up to the main hall, faces split into a half-grin at the shivering group of press stationed by the entrance gate. This morning there had been no one but now the forested grounds were buzzing with families, young couples and climbers decked out in full hiking gear, their excitement mounting as the priests began performing the first rituals.

Dating back to the Heian period, Ogamiyama Shrine, along with Daisen-ji temple which sits just below on the mountain slope, was once part of a thriving center of “shugendo” worship. Climbing the mountain was banned to normal folk before the Edo period, allowing for the natural conservation of an expansive beech forest that is now under the protection of the Daisen-Oki National Park.

Around 3,000 mountain ascetics came to train on Mount Daisen up until the Meiji era “shinbutsu-bunri,” when the large network of branch temples declined with the separation of Shinto and Buddhism.

Four worship halls and 10 branch temples are all that remain of the once bustling temple town. You can glimpse what it must have been like with a traditional temple stay at Sanraku-so, located just before the entrance to Daisen-ji.

Ogamiyama Shrine is an incredible building; the tall crumbling steps leading up to the shrine are framed by towering beech trees and a mist resting poetically on the curled edges of a distinctive bark roof. Inside, the rooms lead into one another in the shape of an H according to the “gongen-zukuri” style, connecting the worship hall, hall of offerings and the main sanctuary together.

Suddenly, everything is silent. The sound of the head “yamabushi” sounding the horn cuts into the darkness and the parade begins. From where I’m standing at the bottom of the steps, I see a wave of fire emerge from the top and start to flow down like lava. It makes me think of medieval peasants on a witchhunt and is Hollywood-spectacular – just for a second, I slip through time into another world.

Mount Daisen is considered to be the home of the first Shinto god and ancestor of Japan. Its mythology permeates the towns and communities that surround it, detectable in the unexpected giant demon sculptures overlooking an isolated row of farmhouses or the smiling stone “jizo” statues that poke out of the grass along the curving roads.

During warmer climes, a three-hour hike will take you to the top via one of two main routes. Staff at the Daisen Tourist Information Center encouragingly claim that both are easy enough to be regularly tackled by local elementary school kids on geography trips. The center, in a Swiss-style chalet at the bottom of the hill leading up to Daisen-ji temple, provides advice on making the climb as well as other things to do in the area.

Throughout the year, cozy “minshuku” or guesthouses offer family-style lodging in the main town and at various points along the hiking trails. An even cheaper option might be one of the campgrounds run by the National Park Service near the Gouenzan Ski Area.

Spiritual high on Mt Daisen (Houki Town website)

As the ambassador for the region’s growing ecotourism movement, Daisen’s carefully preserved streets and traditional, sustainable architecture reflect the conservation of the often surprising natural landscape that makes up much of Tottori-ken. The sprawling sand dunes along the San’in coast are the first piece of the prefecture’s puzzle of geographic wonders when you arrive via Tottori airport, nicknamed Tottori Sand Dunes Conan after the manga hero (whose author is a Tottori native).

From the mountains to the sea, outdoor activities flourish. Tourist brochures are filled with photos of mountain biking, horseriding, snorkeling, boat cruising, paragliding and sandboarding, all set against jaw-dropping backdrops.

In the mountain’s foothills, the village of Houki is straight from a postcard, dotted with quaint holiday homes and picturesque rest stops. This is where we retreat to when the rain clears the following day, stopping for brunch in an adorable Totoro-themed cafe. Sitting in the sunshine I think of the climbers who gathered at dawn for the first summer ascent of the mountain and wonder if they made it ok. Seeing the majestic peak of Daisen soar into the sky in the distance, I can believe that they did.

Nice commentary, I’ve been to the sand dunes ones!

Did you ride a camel?