The famous garden at Ryoanji shows how Zen Buddhism absorbed the native tradition of reverence for rocks

Reading Zen in the Rocks by Francois Bertbier (translated with a philosophical essay by Graham Parkes) Uni of Chicago Press, 2000

Understanding the role of rocks in Japanese culture, and specifically in Shinto, has been something of a quest for Green Shinto. Here is a book which does much to throw light on matters that have long intrigued us. Though the focus is on the dry landscape gardens (karesansui) so beloved of Zen, the book has much to say about the wider subject and its background.

Whereas Green Shinto has previously asserted that the cult of rocks came over with Korean shamanism (the result of southern migration from Altaic shamanism), this book makes no mention of that but looks instead to the Chinese tradition of litholatry. And in the philosophical essay by Graham Parkes, there is the assertion of origins too in the ancient cosmology of China.

For early Chinese, humans lived in a giant cave of which the sky formed the ceiling. That the sky should be made of rock can be seen as a logical conclusion from the way meteorites fell to earth, for they were presumed to be bits of the celestial covering that had fallen off. In similar manner mountains were seen as huge blocks or stalactites that had descended to earth. Their heavenly provenance was not their only distinguishing feature, for in the precipitous fall they had accumulated huge amounts of energy (known as chi or qi). It helps explain why rocks that fell to earth are traditionally treated as divine in Japan.

Another vital point the book makes is that whereas the West has an established dichotomy between animate and inanimate, for the Chinese there was a continuum of existence with chi energy running throughout. The dichotomy such as there was rather between yin and yang. The earth was yin, mountains thrusting upwards were yang. The landscape was thus pulsing with energy, seen graphically in the Japanese word for landscape sansui (mountain – water).

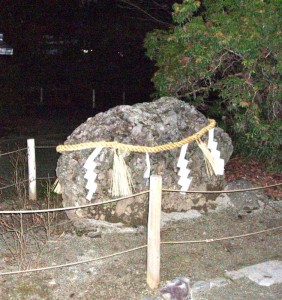

Since rocks constitute the very material of a mountain, they came to be seen as a microcosm of it. They were thus held to possess the same properties and energy as the original mountain. Though the book does not go into this, as it is concerned with Zen, the notion sheds light on Shinto practice. Kami in ancient times descend from heaven into mountains, the nearest point on earth, and Amaterasu’s offspring famously descended on Mt Takachiho in Kyushu. If kami could descend into mountains, they could also descend into the representation of a mountain, i.e. rocks. And here we can understand the possible evolution of iwakura, or sacred rocks.

In this way we can see that in ancient Chinese thought the rock was of a mountain, and the mountain was of heaven. Small wonder that Daoists liked to retreat into caves to seek the ultimate reality. Small wonder too that Bodhidharma spent nine years meditating in front of a rock face. The result was that Buddhists came to incorporate the nature of sacred rock into their philosophy. Zhanran of the Tiantai School for example claimed that even non-sentient beings have Buddhist nature.’ And in Japan Saicho, founder of Tendai, spoke of ‘the Buddha-nature of trees and rocks’.

Garden development

In Shinto it is usual for the area to the south of the main shrine building to be flat and covered with white sand or gravel. It is a place of purity where the kami will be honoured and entertained. Much of Zen in the Rocks is concerned with decoding the famous garden of Ryoan-ji in Kyoto, and it is pointed out that the dry landscape there lies to the south of the main building in Shinto fashion and is on a piece of level land covered with gravel. The Shinto preference for purity, simplicity and naturalness was woven into the Zen tradition.

Sand cones at Kamigamo Jinja. The Zen temple of Daisen-in has a similar pair in its front dry landscape garden.

Buddhism incorporated other aspects of Shinto too. One example is the use of sand cones at Kyoto’s Daisen-in, which is located in the Zen monastery of Daitoku-ji. Its rock garden contains two sand cones which mirror those at Kamigamo Shrine. These may have originally served a purpose similar to the use of red carpets today, in other words prior to the visit of an important dignitary or to the holding of a ritual event the sand from the cones would be spread over the forecourt as a form of purification and renewal. In other words, the cones were a means of storing spare sand, and over time they came to be seen as agents of purification in themselves. Something similar happened at the Zen temple of Ginkaku-ji, where the famous tall cone of sand, said to represent Mt Fuji, was originally just a garden device to keep extra sand when needed.

Zen in the Rocks is relatively short and though it focusses on the rock garden, it offers a range of unexpected insights in the role of rock in Japanese culture. It shows for instance how the Heian garden of pond and vegetation transmuted into the bare rocks and pebbles of Muromachi times. This was part of the Zen concern with pointing to the root of things and stripping away the inessential. In this way the Buddhist emphasis on perpetual change and the transience of life, given emphasis in the Heian garden, was replaced in the Zen garden with symbols of permanence and the eternal.

‘Brother rock’ may seem an odd concept to Westerners, but if you think in terms of the Big Bang, we all share common origins. In considering the changing attitudes to nature in the Sino-Japanese tradition, this book helps us to look at rock anew. Not as something dead, sterile or alien. But as fundamental to our place in the universe. Fundamental to ourselves. As Alan Watts pointed out, the giant rock on which we travel through space is ultimately the source of our existence. The spirit in the rock is ourselves.

For more on rocks, please see the list of categories in the righthand column and browse through the relevant section. For Alan Watts on rock, see this entry here.

In western mythology mountains are places of refuge, the source of wisdom and may conceal a devine being (always female).

Really? A source of wisdom certainly, and easy to understand why, but I didn’t know the divine being was always female. That doesn’t pertain of the gods of Mt Olympus, for example…