Pilgrims on the Kumano Kodo (Old Pathways), near Nachi Waterfall

The academic Michael Pye is known for his work on Buddhist pilgrimages, though in his book on the subject he devotes a chapter to consideration of comparable Shinto practices. The piece below is an abridged version of a paper based on this that is available with accompanying illustrations at academia.edu.

***********

‘The Structure of Religious Systems in Contemporary Japan: Shintô variations on Buddhist pilgrimage’ by Michael Pye

While Japan is well known for its Buddhist pilgrimages in Shikoku, in the Kansai region, and indeed all over the country, the more recent phenomenon of Shintō variations on this theme seems to have escaped notice so far. Making a journey to a single, specific Shintō shrine is a basic, recognizable and even important feature of Shintō.

Amy Chavez, Green Shinto friend, on the Shikoku Pilgrimage trail

Such a journey is known as o-mairi, the term used to refer to any religious movement directed towards a sacred focus at the level of primal religion. O-mairi may be very long and arduous or it may be extremely short. Historically speaking, the most dramatic example of o-mairi in Shintō, which certainly qualifies to be considered in the general context of pilgrimage, is the journey to the great Ise Shrine, a journey known in its heyday in the early part of the nineteenth century as o-Ise-mairi (c.f. Nishigaki Seiji 1983).

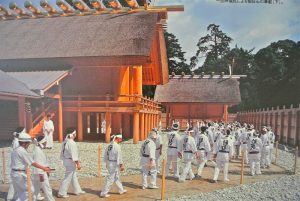

Ise Shrine at the time of the shikinen sengu series of rituals, which when completed draws the biggest number of pilgrims in Japan

However we are concerned here with the more specific phenomenon of circulatory pilgrimage (o-meguri) in Shintō. This may be regarded as a most interesting secondary phenomenon, both for Shintō and as concerns the wider theme of circulatory pilgrimage. It is evidently modelled on the Buddhist pilgrimages, which are older, and perhaps more directly on the Seven Gods of Fortune circuits.

At the time of writing, it appears that the idea of visiting a number of Shintō shrines and collecting the “seal” or “stamp” (shuin) of each one is becoming more and more widespread. Since the older Buddhist meaning of paying for the “seal” is in such cases completely lost, one might compare this practice rather with stamping a souvenir book with the rubber stamp of historic or remote railway stations. Such rubber stamps with inkpads are usually available somewhere in the waiting room or entrance hall of the station, and their use costs nothing.

At Buddhist temples by contrast, the “seal” has the rather complicated older significance, admittedly no longer evident to all, of being a receipt for a donation intended to enable a monk to copy a sutra on one’s behalf (not that this is in fact done as a direct result). On the other hand the visit to a Shintō shrine will usually be linked to a request for supernatural assistance in some matter or other. Thus the use of the stamp must be understood as part of the transaction, however lighthearted the mental connections may be. It will therefore cost something.

Traditional pilgrim garb was natural, simple – and hard on the feet.

A straightforward example of pilgrimage round linked Shintō shrines is known as Hassha Fukumairi or, literally, Good Fortune Visit to Eight Shrines. A fuller name is Good Fortune Visit to Eight Shrines in Downtown Tokyo. Significantly, another variation is Shitamachi Hachifukujin Meguri. In this designation hachifukujin means “eight gods of good fortune”, so that an association with the traditional Seven Gods of Fortune is created, although none of them are identical with these. Various leaflet-sized maps are provided for this circuit, showing convenient underground railway stations and in one case linking the shrines with an arrowed route. There is no numeration or any obligatory order for visiting.

Benten, the only female in the Seven Lucky Gods (Shichifukujin) and a muse of music and creativity, associated with water and the unconscious

Similar linkages of shrines are known in Kyōto. Indeed it is possible to see here a different starting part for the encouragement of sequential acts ofo-mairi. The major shrine known as Imamiya Jinja has within its grounds a whole series of sub-shrines which are listed (with the ending -sha). Visitors are encouraged to stop and pray before all of them. In commemoration they may purchase a large sheet of paper bearing the names of these shrines with a different seal for each.

In the centre is a kind of takarabune [treasure ship] reminiscent of those in which the Shichifukujin are sitting, but in this case with the name of Imamiya written on the sail. This is surrounded by an elevating text, which runs as follows: “By having a sincere heart, bright and pure thanks to the light of the very first day at the beginning of the year, you will find happiness at the eleven shrines in these grounds both now and throughout the year. Whosoever prays whole-heartedly will receive this wealth bestowing ship as the august token of the high, most revered great kami.” The conceptualisation and marketing of this remarkable assembly of divinities was initiated, according to a shrine attendant, “about ten years ago”, that is, in the early 1990’s.

A circuit which takes people around much of the city is known as “Kyōto Fourteen Shrines Seal Pilgrimage”, or “Kyōto Sixteen Shrines Seal Pilgrimage”. For this pilgrimage, or round tour, a large horizontally arranged paper is provided on which the seals of the various shrines can be stamped, thus encouraging visits to all of the shrines. Starting with New Year 1997 (Heisei 9), two shrines were added, making sixteen in all. The shrines added in 1997 are Goryō Jinja (KamiGoryō Jinja) and Imamiya Jinja. A reason for adding these two was cited at Imamiya Jinja as being that one was to the east and one to the west of a major road in Kyōto known as Horikawa, which runs from south to north. This gives a feeling of comprehensiveness or inclusiveness. Evidently, with similar reasoning, almost any shrines could be added to any pilgrimage series. An underlying motive is presumably that these two shrines also would like to participate in the business, especially at New Year.

We see here therefore a combination of competition and cooperation between the shrines. In the main, an appeal is made to the idea that one can somehow maximise benefit by visiting more than one shrine, indeed several. At the same time, there are only Shintō shrines in these groups, and this leads to a gentle emphasis on the Shintō view of the world.

By contrast the Shichifukujin remain entirely in the realm of the transactions of primal religion. The Shintō linkages seem to lead into a slightly more specialised consciousness The paper on which the seals are to be stamped is provided in a large envelope, which bears the following text: “Kyōto Sixteen Shrines Seal Pilgrimage New Year Shrine Visit”. In the refreshing spirit with which we meet the New Year, taking this paper for the seals with us as we go round to worship at the sixteen shrines, we pray that we may receive the virtues of each one of the great kami for body and soul alike. When this paper for the seals of the pilgrimage to the sixteen shrines is completed it will serve as a protection for everybody for the whole year, so please pay reverence to it carefully.” The implication of this is that the completed paper should be kept in a respected place at home e.g. on the house-altar (kamidana), so that prayers may be said before it throughout the year.

Stamp books proving completion of pilgrimages can be offered up on the kamidana to have one’s merit recognised by the kami

Regarding the stamps received on Buddhist pilgrimages…

Unless there are older roots that I am unaware of, I believe this custom began on the Shikoku pilgrimage, and its origins are political rather than spiritual. In a land of suppressed freedom of movement, the stamps proved to authorities that the bearer was indeed a pilgrim who’d undergone the proper circuit, and not a ne’er-do-well travelling around to forment trouble.

Interesting point, thanks. It certainly makes sense in terms of control, so if true it would mean the practice only began in Edo times, or just before. It would also suggest that the Shikoku idea of taking your stampbook with you at death as a kind of passport into the next world was developed afterwards…