In the middle of Kyoto is a large area of parkland containing the Former Imperial Palace, where lived Japanese emperors from 1331. Following the Meiji Restoration, the young emperor moved in 1869 to Edo, newly renamed as Tokyo, and with him moved the imperial court.

Following the relocation to Tokyo, the site was left to deteriorate until a project to reclaim it for the general public turned it into open parkland. Now it’s officially known as the Kyoto Gyoen National Garden, though locally it’s simply called Gosho (御所), Honorable Place.

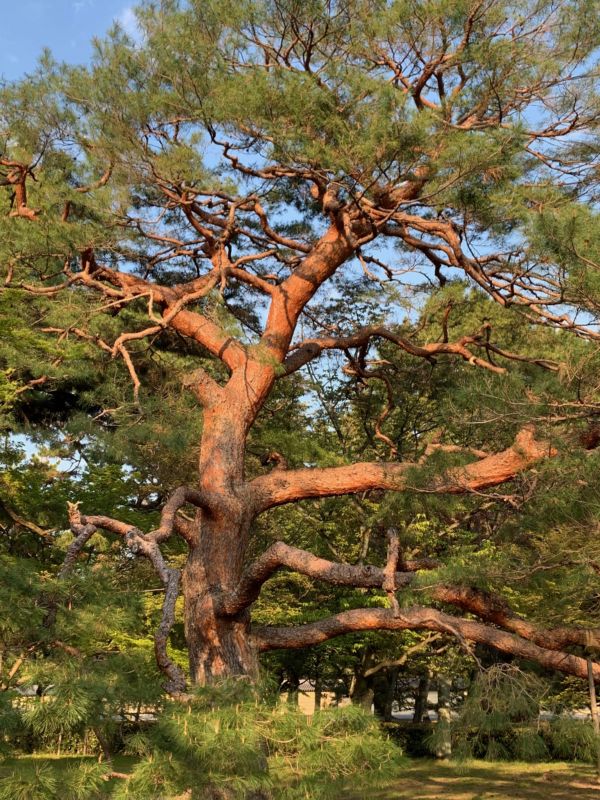

The parkland is open and spacious, full of dog walkers and joggers and sightseers. It’s 700 meters wide and over a kilometer in length. In 2005 a State Guest House (Geihinkan) was added where foreign dignataries are put up. Altogether there are some 50,000 trees, including a plum grove and weeping cherry blossom, with a splendid display of bent pines and soaring camphor. Taken overall, it makes for a veritable tree exhibition.

During the Edo Period the estate had been crammed full of aristocrats, with the houses of some 200 court nobles packed in around two palace estates. A notice board at the entrance shows the layout as it used to be, and though the houses of the court nobles have gone now, there remain three Shinto shrines, open to the public.

By name, the shrines are Munekata Jinja, Itsukushima Jinja and Shirakumo Jinja. The first two are familiar, as they are named after major Shinto shrines near Hiroshima and Fukuoka, both of which happen to be World Heritage Sites. The third, Shirakumo, is relatively obscure. In this mini-series, we’ll be taking a closer look at the three shrines and considering what Shinto meant for the aristocracy.

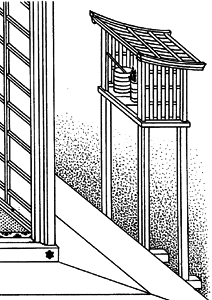

Interestingly, there are no Buddhist temples within the imperial estate, though throughout Japanese history emperors and their followers practised Buddhism and sponsored many of the city’s large temples. Like any individual, the nobility sought salvation and this was not on offer from Shinto. From what I can gather, in their private practise they had at home a Buddhist ‘akadana’ for placing holy water and other offerings.

It would seem that the Shinto shrines speak to a different kind of attachment, for if Buddhism was universal Shinto was fiercely particularist. Through their worship of kami, the imperial aristocrats showed attachment to their native land and the spirit of place. This is exemplified by the last emperor to be born and die in Gosho, Emperor Komei (1831-1867), who famously made a special outing to Shimogamo Shrine to pray that foreigners be expelled from the sacred soil of Japan.

The close ties of the court nobles to the patriotic leanings of Shinto became all too apparent during the Meiji Period, when a new emperor-centred government sponsored State Shinto out of a desire to reject the Tokugawa favouring of Buddhism. The defeat of WW2 did little to cut the ties, as was seen during the ascension rites of the new Reiwa emperor last year when Shinto rituals were much in evidence while Buddhism was sidelined.

Walk around the Former Imperial Palace parkland today, and you can feel that in its trees and sense of history the ruined estate speaks powerfully to the animist and ancestral leanings of Shinto. Deified aristocrats and personalised natural phenomena comprise the park’s deities. And presiding over them is the spirit of a once secluded head priest – the emperor himself.

Leave a Reply