Jomon museum artifacts are being put together in a stunning photography collection (this and the photos of figurines below courtesy Tadahiro Ogawa)

New light on Jomon millennia

by EDAN CORKILL Japan Times SEP 28, 2013 (Abridged version below; for the original article, click here.)

The Jomon Period of Japanese history is so shrouded in the mists of time that any bid to fathom its secrets stretches even the usual astonishing bounds of prehistoric archeology.

Yet as amateurs and experts alike have continued unearthing and studying 2,000- to 10,000-year-old examples of Jomon pottery and stone tools for more than a century, the pieces of the puzzle are gradually coming together.

The fascinating dogū figures of Jomon times

It is only six years ago, for instance, that the discovery of unusually large beans — or the holes where they had been encased in the clay of Jomon Period pots — provided concrete evidence that people living in these islands so very long ago had been able to domesticate certain plant species.

For the last 30 years Tadahiro Ogawa is one who has dedicated himself to photographing Jomon Period artifacts — and to date he has around 30,000 of them in his picture archive.

In fact the Tokyo resident has photographed at pretty much every one of the more than 500 museums nationwide that stocks objects from the Jomon Period — which is conventionally dated at from around 12,000 B.C. to 300 B.C.

What are we nowadays to make, for example, of giant cooking pots standing 60 or 70 cm tall and covered with richly ornate decorations — some of them representative of animals such as snakes and frogs; others, to our eyes at least, completely abstract?

And then there are even less practical objects: three-dimensional depictions of animals or people. Some of the dogū, as such figurines are called in Japanese, have broad, triangular-shaped heads and large eyes that seem to have more in common with science-fiction aliens than people.

A female figurine - used in fertitlity rites?

Through generations past, the very oddness of Jomon pottery has tended to define it in the public’s mind. Thus it was appropriated by mid-20th-century artist Taro Okamoto, who saw in it a reference point to postulate a “new” and uniquely Japanese form of visual expression.

But, as far as photographer Ogawa is concerned, such deliberate mystification of Jomon Period culture has an unfortunate legacy, in that it has planted in the minds of contemporary Japanese the notion that the people inhabiting these isles back then were quintessentially different and distant — so much so that they belonged to an utterly separate world.

Ogawa’s primary goal in his tireless work is to bridge the gulf of time and comprehension; to create a window through which to behold a people many thousands of years ago who were not so different from Japanese today.

“The fact is, we Japanese are connected to these people by blood, and they lived normal lives, hunting and making objects such as these in the same natural environment that we inhabit now,” the 70-year-old told The Japan Times.

“They had hopes and fears and complex lives. And if you look closely enough at the objects they left behind, you can get a sense of what those were.”

The distinctive style of Jomon pottery

The exhibition rooms at the Matsumoto City Museum of Archeology, tucked into the mountains of Nagano Prefecture, have dozens of dogū on display. The little clay figurines and faces, most between 10 cm and 20 cm in height, stand in glass cases alongside other types of Jomon artifacts — large pots, stone tools and so on.

Made of clay and having survived for up to 7,000 years buried in shallow soil — many in Nagano’s valley floors — the dogū are about as resilient as any artifact you’ll find in a museum. Hence there is no need for air conditioning, or even precise humidity control. Indeed, more than one glass display case seemed to have recently acquired new occupants in the form of dead insects.

“Some of these dogū I shot a few years ago, but only in black and white,” Ogawa said. “Today I’ll shoot this one, that one and that row at the back.” A museum assistant began opening the cabinets and transferring the pieces to paper-lined trays.

Ogawa next moved to another room, where four large plastic crates were soon opened to reveal hundreds more of the little dogū creatures — all lined up in rows on beds of tissue paper like oddly shaped chocolates in a box — but prehistoric confections that still keep their roles in long-gone human lives secret from even the most erudite of scholars.

One of the mysterious dogū figurines

For all the resemblance of many to beings from outer space, though, others are easy to read as depictions of pregnant women, ones giving birth or nursing small children.

Takashi Tsutsumi, chief curator of the Asama Jomon Museum in Nagano Prefecture, who was accompanying Ogawa during his shoot, explained that “the average lifespan of Jomon people was around 30 years, so childbirth and raising children were the central events around which their lives revolved. Naturally, therefore, they made icons symbolizing both fertility and virility.”

Other small clay figurines depict the kinds of animals that Jomon people hunted — wild boar, bears and salmon among them. In dull white boxes, raked by harsh lighting that erases their textures, such objects tend to seem childlike — much like crude lumps of hand-molded clay. But, as soon became apparent when they were photographed from the right angle in proper lighting, they come alive.

The first piece to be photographed was a small head, which Ogawa said was from the late Jomon Period. After carefully placing it on the paper he spent several minutes adjusting multiple lights and mirrors to achieve the lighting effect he sought. Suddenly what had been a small and apparently inconsequential clay lump leapt to life as shade and shadow brought out a proud forehead and ramrod-straight nose.

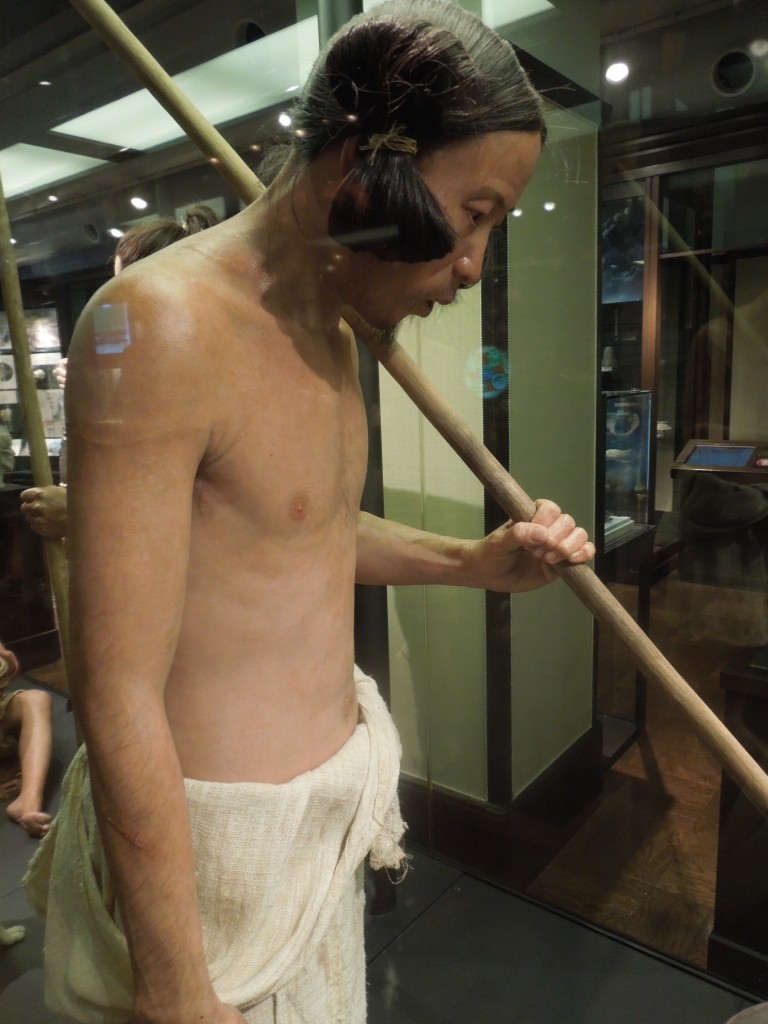

Jomon man (in the National History of Science Museum in Ueno, Tokyo)

The second piece was actually two — both halves of a figurine that Ogawa decided he would reassemble for the photograph. “This was excavated broken like this in two parts, so for the archeologists it is important that it be displayed in that same, broken arrangement. But for me the important thing is to re-create what it was like in real life — not as some dead relic,” he said.

Ogawa’s entree into the Jomon world came about by way of an express train and a particularly unusual piece of equipment known as a slit camera. That was because, back in the early 1980s when he was working as a photographer for news magazines, a friend once asked him for advice. “At first I tried things like Grecian urns, but I soon found myself drawn to Jomon pottery. The decoration wasn’t uniform, so it seemed to have so much depth,” he said.

In addition to its dogū figurines, Jomon pottery is well known for giant, ornately decorated pots and pitchers. Ogawa soon began experimenting with how to shoot such objects and, to his surprise, he found that the response in archeological circles was extremely positive.

“No one had ever achieved such clear photographs of the full circumference of Jomon pots,” explained Masafumi Ono, an archeologist with the Kofu City Board of Education in Yamanashi Prefecture. “To be able to see the full pattern so clearly really allowed the study of these bowls to progress.”

Joman woman (National History of Science, Ueno, Tokyo)

And yet, despite his years of experience with Jomon pottery, Ogawa is wary of wading into arguments over why the objects were made or how they were used.

“To be honest, when I first started doing this I assumed the big pots were for keeping seeds or something like that in them. But when I mentioned that, the academics all laughed — because there was no agriculture in the Jomon Period. It turns out they used these big ungainly pots for cooking!” he said.

Tsutsumi explained further: “The point about the Jomon people was that they were hunter-gatherers — but they were sedentary. They had stone tools so they could cut trees and build houses, and there was enough natural bounty around them — acorns and other plants, wild boar, deer and salmon — that they could more or less remain in the same place.

If they were mobile, moving with migrating animals for example, then they wouldn’t have made such decorative pottery — especially nothing as big and heavy as these large pots,” he said.

While the Jomon people do seem to have also domesticated some species of beans and sesame for its seeds, they did not harvest those at any scale. The end of the Jomon Period is in fact demarcated by the emergence of proper farming techniques — probably following the arrival of a new population from mainland China around 2,000 years ago. That influx of new blood also coincides with a marked simplification of the pottery being made as the emphasis seemingly shifted from decoration to utility. As a result, pottery from the subsequent Yayoi Period that roughly spanned 300 B.C. to A.D. 300 is the Modernism to the Jomon Period’s Art Nouveau.

“The arrival of agriculture also meant the birth of the concept of ownership, as food could then be hoarded,” Tsutsumi pointed out, adding that this led to a phenomenon familiar to us all today: conflict.

“If you look at graves from the Yayoi Period, you find skeletons without heads or with severe injuries. Such things are very rare in Jomon Period graves,” Tsutsumi said. “In the Jomon Period they of course had the stress of having to find food every day, but it may have been the last time in history that society in Japan was really peaceful.”

It thus seems likely that the explanation for the wondrous oddity of Jomon Period pottery lies in the geographical, social and environmental conditions of the time, which enabled people to follow a little-changed sedentary hunter-gatherer lifestyle of relative abundance for an unimaginable span of more than 8,000 years.

“That meant that for many many generations they were coexisting in close proximity and in a natural state with the bears, boars, snakes and turtles that you see depicted in their pottery,” Ogawa said. “I think the depth of their relationship with nature is the one thing that really becomes clear as you look closely at these objects.”

Then, after looking closely indeed at a large pot wreathed in a complex snake motif, this remarkable “prehistoric photographer” carefully measured its dimensions and set up his lights. After that, it was really as if each serpentine coil came elegantly to life.

“In contemporary society, of course, we have completely lost that deep connection with nature — you can see that in the damage caused by the (Great East Japan) earthquake and tsunami of two years ago,” he said. “Hopefully, some people will be reminded of that lost connection through my photographs.

*************************************************************************************************

Tadahiro Ogawa’s latest book, “Jomon Bijutsukan (Jomon Art Museum),” was published this year and features more than 500 photographs of Jomon Period artifacts. It is available from museum bookshops, Amazon.co.jp and other outlets. An online translation of the book is also being produced at jomonarts.com.

Tadahiro Ogawa, seen at work in museums in Nagano Prefecture believes really good photos of Jomon artifacts can greatly help today's Japanese connect with their forebears. (photo by EDAN CORKILL)

Leave a Reply