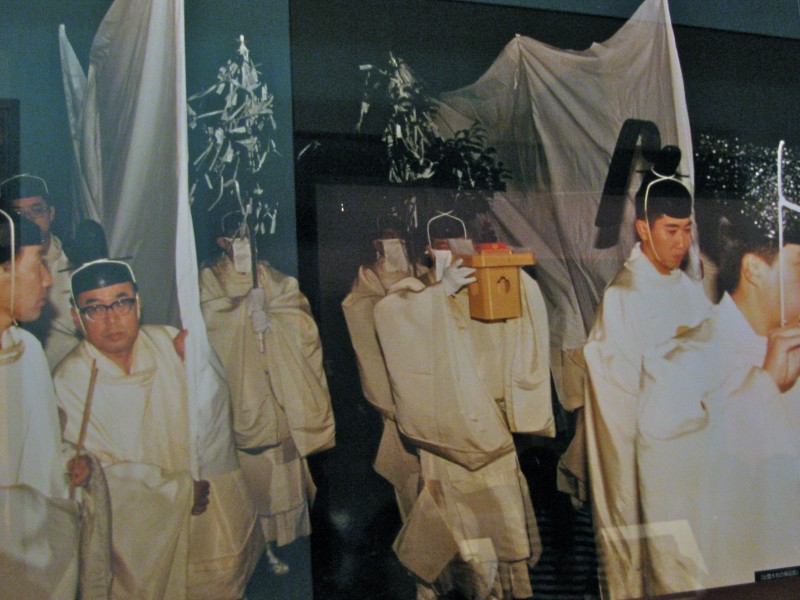

Inside the Haiden of Izumo Taisha

‘Of all Shinkoku [land of the gods] the most holy ground is the land of Izumo.’

So wrote Hearn in the early days of his infatuation with Japan when he was resident in Matsue and an unabashed admirer of the region. One might think therefore that his statement about the spiritual supremacy is mere enthusiasm. Yet he had a point, for historically speaking, according to mythology, Yamato had ceded spiritual dominion to Izumo in return for its recognition of Yamato’s hegemony in worldly terms. If it were not for the imperial imposition of Ise on the country as the nation’s supreme shrine, Izumo would rightfully have claimed the status.

A gaijin tries to get a coin to lodge in the world’s largest shimenawa sacred rope for good luck

Teeuwen and Breen are bringing out a much awaited book on Ise in the New Year. Someone should do the same for Izumo, for it is high time that Hearn’s championing of the shrine was taken up. Hearn himself was much taken with the shrine. After securing a letter of introduction to its 81st head, Senke Takanori (a record Ise is unable to match), he took a trip by boat that he describes in rapturous terms – the boat is ‘liliputian’, a ‘toy model’, with ‘a charming naked boy serving tea’ and an ‘indescribably lovely view’.

On the way to Izumo there are ‘beautiful shapes’, ‘masses of absolutely pure color’, and ‘the loftiest mountain… proudly towering with ghostly blue and ghostly white.’ It is a ‘luminous day’, with the ‘vapoury land’ spelling ‘divine magic’ and ‘Over all arches a sky of color faint as a dream.’

It is in his description of the monumental shrine of Izumo, however, that Hearn comes into his own, evoking the sense of awe and gratitude that lie at the heart of Shinto…. [note that Hearn was writing before the modern convention of referring to temple for Buddhism and shrine for Shinto].

There seems to be a sense of divine magic in the very atmosphere, through all the luminous day, brooding over the vapory land, over the ghostly blue of the flood – a sense of Shinto. With my fancy full of the legends of the Kojiki, the rhythmic chant of the engines comes to my ears as the rhythm of a Shinto ritual mingled with the names of gods:

Koto-shiro-nushi-no-Kami

Oho-kuni-nushi-no-Kami… ‘there are eight hundred myriads of Kami in the Plain of High Heaven’ – so says the Ancient Book. Of these, three thousand one hundred and thirty and two dwell in the various provinces of the land; being enshrined in two thousand eight hundred and sixty-one temples. And the tenth month of our year is called the ‘no-God Month,’ because in that month all the deities leave their temples to assemble in the province of Izumo, at the great temple of Kitzuki; and for the same reason that month is called in Izumo, and only in Izumo, the ‘God-is-Month.’ But educated persons sometimes call it the ‘God-Present-Festival,’ using Chinese words. Then it is believed the serpents come from the sea to the land, and coil upon the sambo, which is the table of the gods, for the serpents announce the coming; and the Dragon-King sends messengers to the temples of Izanagi and Izanami, the parents of gods and men.

The kami of Japan are carried up the beach from the sea after their arrival for the kamiari festival

***********

‘Is not this great temple of Kitzuki,’ I inquire, ‘older than the temples of Ise?’

‘Older by far,’ replies the Guji, ‘so old, indeed, that we do not well know the age of it. For it was first built by order of the Goddess of the Sun, in the time when deities alone existed. Then it was exceedingly magnificent; it was three hundred and twenty feet high.

***********

I cannot suppress some slight exultation at the thought that I have been allowed to see what no other foreigner has been privileged to see – the interior of Japan’s most ancient shrine, and those sacred utensils and quaint rites of primitive worship so well worthy the study of the anthropologist and the evolutionist.

But to have seen Kitzuki as I saw it is also have seen something much more than a single wonderful temple. To see Kitzuki is to see the living centre of Shinto, and to feel the life-pulse of the ancient faith, throbbing as mightily in this nineteenth century as ever in that unknown past whereof the Kojiki itself, though written in a tongue no longer spoken, is but a modern record.

Model of how the shrine might have looked in ancient times when it was the tallest and most ancient building in the whole of Japan.

For previous articles on Lafcadio Hearn, please see Part 5 for the power of his writing, Part 4 for his pagan connections, Part 3 about the Shinto mirror, Part 2 about his house in Matsue, and Part 1 about his relationship with Basil Hall Chamberlain, translator of the Kojiki.

Bloombury Academic just came out with “The Origin of Modern Shinto in Japan: The Vanquished Gods of Izumo”, which traces the role of the Izumo Shrine and its mythology in the formation of the nation of Japan.

Thank you for the input, Steve. It’s a book on my reading list for the coming year, once I finish Hearn’s voluminous writings! If you happen to read it, please report back on what you think of it…

“Teeuwen and Breen are bringing out a much awaited book on Ise in the New Year. Someone should do the same for Izumo, for it is high time that Hearn’s championing of the shrine was taken up.”

Thank heavens, the wish is already fulfilled. Last October saw the publication of:

Yijiang Zhong, The Origin of Modern Shinto in Japan – The Vanquished Gods of Izumo. Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

He draws from primary Japanese sources, which only recently had become available for the public. His book shows clearly how Onamuchi-no-Kami came to be ignored in State Shinto.

I have not yet finished this excellent study, but I think Onamuchi, or Okuninushi-no-kami, the Land Lord Kami, has a better chance to guide the transition of japanese shinto into transnational, or green shinto.

Amaterasu, supreme kami of the shinto pantheon, and Ise Jingu, are less capable for that role, due to their strong lines with Emperor system and Jingoism.

Thanks for the input, Paul, and I couldn’t agree with you more. Nice to get the input of a priest on the subject…