This is an extract from a forthcoming book about travel by train the length of Japan. (For Part One click here.) In 1863, after Japan agreed to open up to the West, Emperor Komei in a formal procession to Shimogamo Shrine went to pray that foreigners would return home. His action was driven by the notion of Shinto as a divine land – ‘kami no kuni’. Though Westerners were reluctantly accepted, restrictions were made as to where they could live, and where they should be buried.

*********************

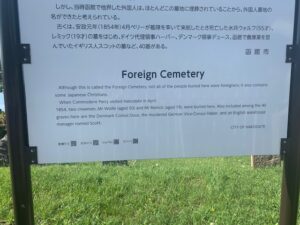

Japan has four sizeable gaijin bochi (foreign graveyards), located in the treaty ports of Hakodate, Kobe, Nagasaki and Yokohama. In Hakodate the first foreign burials took place with the arrival of the first ever foreign ship, for when Commodore Perry arrived in 1854, he brought with him a Mr Wolfe, aged fifty, and a Mr Remick aged nineteen, both recently deceased.

A special cemetery was set up, located on a slope with a fine view of the Pacific. Hydrangea bush and twisted pines beautify the site, and in the summer warmth of late August this final resting place was everything one might wish for – apart from being on the other side of the world.

There are some forty graves in all, comprising American, British, French, Danish, German and, surprisingly, a few Japanese Christians. A nearby cemetery is specifically for Chinese, and there is one for Russians too. Interestingly, there is no mention of nationality in the early gravestones, just a date and occasionally an occupation. The most poignant has the simplest inscription: ‘Baby, May 21st, 1874.’

By midday the temperature had reached 29c, and since there was no one around, I lay on the grass in the shade of a bush, looking out to sea and contemplating death in a distant land. At this point a Japanese couple walked past, and though they must have seen me they showed not the slightest indication of anything unusual. This ability not to see things is a fine art in Japan and a cultural trait foreigners sometimes speak of with envy.

Opposite the ‘gaijin cemetery’ is a Buddhist temple with a graveyard, and to one side there is a third graveyard, reserved for Japanese Christians. It seemed symbolic of the halfway house they occupy. In Edo times Christianity was banned as a tool of colonialism, and it was only in 1873 that it was tolerated though it was not long before it fell under suspicion again for refusal to accept the divinity of the emperor. Still today Christians stand out from the Japanese norm: they keep different festival days, cleave to monotheism and don’t observe ancestral rites (forbidden in the Bible).

The sun was setting as I left, and it felt fitting that the cemetery should mark the last evening of my stay in Hokkaido. The next day I faced the long ride to Aomori, which would take me back to Honshu, and I had mixed feelings. Many years previously, when I wanted to visit Okinawa, Japanese friends had told me it was like a different country, and it was true that away from the capital there was a Polynesian feel. Hokkaido too has the feel of a foreign country, and the humidity and restricted horizons of Kyoto had been mercifully replaced by fast flowing streams and endless greenery. The resulting ease of mind owed itself not just to the openness of the landscape but to the friendliness of the people, descendants of pioneering adventurers who had arrived to build a new life. All in all, it felt indeed as if I had been to a foreign country – without even having to go abroad.

Leave a Reply