Shinto no kyozo to jitsuzo by Inoue Hiroshi Kodansha, 2011

Shinto no kyozo to jitsuzo by Inoue Hiroshi Kodansha, 2011

Here’s a book by a university professor (Osaka Kogyo University, also professor emeritus at Shimane Johou Kagakabu), whose promotion blurb screams ‘Shinto was invented three times!’

Those familiar with recent writings on Shinto will not be surprised by the claim. Personally speaking, I would have ascribed the three times to the late seventh century and the formation of imperial mythology in the Kojiki; the attempt to overthrow Buddhist domination by Yoshida Shinto in the fifteenth century; and the Meiji-era championing of Shinto under the new emperor system after 1868.

According to Inoue Hiroshi, only two of my three guesses would be correct. It’s the first with which he disagrees. What we understand as ‘Shinto’, the professor claims, did not begin until around the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth centuries. It was then that it became an organised religion. Before that it was a loose amalgam of diverse practices derived from Taoism, with little in common and no doctrine.

The creation of ‘Shinto’

For Inoue, systemisation is the key to an understanding of what constitutes a religion. Only with a coherent organisation and ideology, he maintains, can we speak of a religion in the proper sense. In this regard he identifies three developments as key to his theory:

1) An ideology of exoteric-esoteric Buddhism that subsumed Shinto. (The theory, known as kenmitsu taisei, was first put forward by Kuroda Toshio.)

2) Self-identity as ‘a land of kami’ (shinkoku shisou), which came with rising national consciousness.

3) Shrine ranking. A system of 22 Shrines with imperial patronage was set up in mid-Heian times. In late Heian times came the appointment of leading shrines in each province (ichinomiya), which effectively acted as agents of state.

Official Shinto and folk Shinto

Following the above changes, there opened up two kinds of ‘Shinto’. One was the official face, with its imperial myths and centralised practice. The other was what might be called folk Shinto, carried on by ordinary people in traditional manner, with diverse beliefs and local customs. Official Shinto became a way of controlling people, in the way of organised religion. Folk Shinto was rooted in the lives of the people.

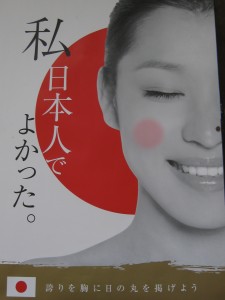

A patriotic religion, or a nature religion? Poster at Suwa Taisha saying 'It's good that I am Japanese.'

Looking at the current state of affairs, Inoue Hiroshi puts forward two recommendations. One is for Shinto to see itself as one of many religions, and not to assert its non-religious ‘we are special’ character. The other is to emphasise the connection with animism and nature.

In terms of a more open and green direction for Shinto, the book is very much to be welcomed. Personally, I’m still inclined to see some kind of ‘Shinto’ emerging around the end of the seventh century, when a conscious attempt was made to systematise the myths and establish divine descent for the Yamato emperor. I’d also add a note to the effect that Shinto should not just see itself as a religion, but as an East Asian religion in particular. This would help counteract the nationalist tendency to think of Shinto as endowing Japan with a specially divine nature.

Verdict: Written in Japanese for Japanese, the book is an important reminder that there are elements within Shinto working towards greater openness and against the idea that Shinto has existed since time immemorial.

*****************************************************************

With thanks to Kyoko Kitazume for her assistance

Interesting; this is on my to-read list, but that list is very, very long…

I’d note that if a religion needs a coherent organisation and ideology, then Shinto is, in fact, not a religion at the moment. Jinja Honcho doesn’t cover everything, and even Jinja Honcho is very aware of the fact that Shinto doesn’t have an ideology, let alone a coherent one.

David, I have noticed the same thing. I have read the Kojiki and Nihongi (English translations) and if I compared it to other religious text that I have read I noticed a huge difference. The Kojiki and Nihongi do not really have any doctrine in it and it is more like a book on the history of a long family lineage. But that is also what I love about it, it is different enough from other religions to kind of be placed in its own little category.

I think John Dougill’s evaluation is a good one and needed, should any new kind ofnotion of a divinely unique Japan should take hold again. John and I agree that religions sprang up spontaneously in every place where a new tribe or nation rose up. During the past hundred and fifty odd years, historians, archeologists, philosophers, sociologists have slowly came to realize this as the history of religions in both the east and the west (and the north and the south) slowly became part of human knowledge. So Inoue’s analysis would greatly benefit by his reading the latest publication of Prof. Robert N. Bellah of Harvard and Cal, Berkeley, that is the culmination of his more than half-century of seeing religion as an integral part of human evolution itself. The book is Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age, published by Harvard’s Belknap Press, 2011.