Our friend Aike Rots is carrying out research on Shinto’s environmental policies. Here is an extract from a piece he has written entitled “Shinto’s sacred forests”. (The full article can be found here.)

Our friend Aike Rots is carrying out research on Shinto’s environmental policies. Here is an extract from a piece he has written entitled “Shinto’s sacred forests”. (The full article can be found here.)

*********************************************************************

Interestingly, in Japan, Jinja Honchō has a conservative profile; until recently, it mainly devoted its attention to controversial issues such as the reestablishment of imperial rituals and symbols, the revision of the constitutional separation of Church (i.e., shrine) and State, and the opposition against equal rights for women and migrants. Accordingly, whereas it has been using environmentalist vocabulary for its English-language PR publications for a while, until recently environmental issues did not figure prominently in its Japanese publications, let alone policies.

However, in the past two decades or so there has been increasing interest in the notion of Shinto as a so-called ancient tradition of nature worship, and within Japan a sizeable academic discourse has emerged surrounding the concept of chinju no mori (sacred shrine forest), in which Shinto ideologues, philosophers, ecologists and forestry scientists participate. This development seems to have exercised some influence on Jinja Honchō as well; there seems to be a movement within the organisation towards an increasing awareness of environmental issues, if only for pragmatic reasons.

The question is whether Shinto really is a tradition of nature worship that is compatible with contemporary conservationist concerns, or not; and whether notions of ‘nature’ and the ‘environment’ within Shinto discourse correspond to uses of the terms by ecologists and conservationists.

Shinto and nature

When studying the relationship between Shinto and nature, one must bear in mind that both concepts are, to a certain extent, historical constructions, the meaning of which is subject to change. The concept ‘Shinto’ is complicated, and carries a variety of meanings. It is intertwined with normative notions regarding the nation, its origins, and its relationship to the imperial family.

Different definitions correspond to different historical narratives and, accordingly, political positions. In other words, ‘Shinto’ is an ideal typical construction, that may be based on actual ritual practices and shrine traditions, but does not equal them.

In any case, there is a fundamental difference between essentialist interpretations of Shinto, which typically assert that Shinto is the ‘indigenous’, ‘ancient’ tradition of ‘the’ Japanese people; and historical constructivist approaches, which see the modern, institutionalised religion Shinto as the product of a variety of historical and ideological developments, that emerged within the context (institutional as well as theological) of Buddhism and Confucianism, and did not become an ‘independent tradition’ until the second half of the nineteenth century. The ahistorical essentialist interpretation continues to be told in popular-scientific introductions to ‘world religions’, travel guidebooks, online encyclopedias and some academic publications.

...... but it's not always clear what ends it serves

In recent years, primordialist and essentialist notions of Shinto have been combined with environmentalist rhetoric, giving rise to something we may tentatively call a ‘Shinto environmentalist paradigm’. Shinto has been redefined as, fundamentally, an ancient animistic tradition primarily concerned with worshipping ‘nature’ and preserving the harmony between human beings and their natural environment. Several foreign scholars have written essays in which they advocated the idea that traditional ‘Shinto’ worldviews could serve as blueprints for environmental ethics. In Japan, a number of actors have been instrumental in this development, including cultural theorists, Shinto ideologues, shrine organisations, ecologists and artists.

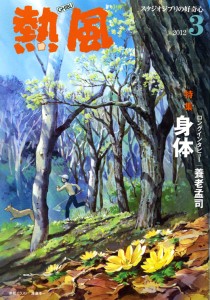

A famous example of the latter is the film maker Miyazaki Hayao, well-known internationally for animated films such as My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, in which environmentalist critique is combined with a creative reimagination of Shinto-esque deities.

Within academia, the ‘Shinto environmentalist paradigm’ has been legitimated by means of a reimagination of prehistorical ‘Japanese’ as living in harmonious coexistence and correlation with their natural surroundings, supposedly expressed in animistic beliefs and practices. Scholars subscribing to this paradigm (such as Umehara Takeshi, Yasuda Yoshinori, Ueda Masaaki and Sonoda Minoru) generally assert that in the modern period, this traditional environmental awareness has been largely forgotten as a result of the import of ‘Western’ technology and ideology, which have caused widespread environmental, moral and cultural deterioration.

In their view, the solution to contemporary problems (social as well as ecological) therefore lies in the reestablishment of ancient modes of relating to nature; i.e., in the establishment of an ‘animism renaissance’, and the preservation and reconstruction of sacred forests, so-called chinju no mori. Much recent discourse has focused on the latter concept, and a movement has emerged which focuses on raising public awareness about these forests, assisting shrines in forestry practices, and, in the process, redefining the role of Shinto in Japanese society.

****************************************************

An interesting response to the above has been made by Arne Kalland, professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo, which will follow in Part Two.

Shinto's commitment to environmentalism remains far from clear

Leave a Reply